Chapter 4 Psychometric Validity: Basic Concepts

The focus of this lecture is to provide an introduction to validity. This includes understanding some of the concerns of validity, different aspects of validity, and factors as they affect validity coefficients.

4.2 Research Vignette

This lesson provides descriptions of numerous pathways for establishing an instrument’s validity. In fact, best practices involving numerous demonstrations of validity. Across several lessons, we will rework several of the correlational analyses reported in the research vignette. For this lesson in particular, the research vignette allows demonstrations of convergent/discriminant validity and incremental validity.

The research vignette for this lesson is the development and psychometric evaluation of the Perceptions of the LGBTQ College Campus Climate Scale (Szymanski & Bissonette, 2020). The scale is six items with responses rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate more negative perceptions of the LGBTQ campus climate. Szymanski and Bissonette have suggested that the psychometric evaluation supports using the scale in its entirety or as subscales composed of the following items:

- College Response to LGBTQ students:

- My university/college is cold and uncaring toward LGBTQ students.

- My university/college is unresponsive to the needs of LGBTQ students.

- My university/college provides a supportive environment for LGBTQ students. [un]supportive; must be reverse-scored

- LGBTQ Stigma:

- Negative attitudes toward LGBTQ persons are openly expressed on my university/college campus.

- Heterosexism, homophobia, biphobia, transphobia, and cissexism are visible on my university/college campus.

- LGBTQ students are harassed on my university/college campus.

A preprint of the article is available at ResearchGate.

Because data is collected at the item level (and I want this resource to be as practical as possible), I have simulated the data for each of the scales utilized in the research vignette at the item level. Simulating the data involved using factor loadings, means, standard deviations, and correlations between the scales. Because the simulation will produce “out-of-bounds” values, the code below re-scales the scores into the range of the Likert-type scaling and rounds them to whole values.

Five additional scales were reported in the Szymanski and Bissonette article (2020). Unfortunately, I could not locate factor loadings for all of them; and in two cases, I used estimates from a more recent psychometric analysis. When the individual item and their factor loadings were known, I assigned names based on item content (e.g., “lo_energy”) rather than using item numbers (e.g., “PHQ4”). When I am doing psychometric analyses, I prefer item-level names so that I can quickly see (without having to look up the item content) how the items are behaving. While the focus of this series of chapters is on the LGBTQ Campus Climate scale, this simulated data might be useful to you in one or more of the suggestions for practice (e.g., examining the psychometric characteristics of one or the other scales). The scales, their original citation, and information about how I simulated data for each are listed below.

- Sexual Orientation-Based Campus Victimization Scale (Herek, 1993) is a 9-item item scale with Likert scaling ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (two or more times). Because I was not able to locate factor loadings from a psychometric evaluation, I simulated the data by specifying a 0.8 as a standardized factor loading for each of the items.

- College Satisfaction Scale (Helm et al., 1998) is a 5-item scale with Likert scaling ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Higher scores represent greater college satisfaction. Because I was not able to locate factor loadings from a psychometric evaluation, I simulated the data by specifying a 0.8 as a standardized factor loading for each of the items.

- Institutional and Goals Commitment (Pascarella & Terenzini, 1980) is a 6-item subscale from a 35-item measure assessing academic/social integration and institutional/goal commitment (5 subscales total). The measure had with Likert scaling ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores on the institutional and goals commitment subscale indicate greater intentions to persist in college. Data were simulated using factor loadings in the source article.

- GAD-7 (Spitzer et al., 2006) is a 7-item scale with Likert scaling ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Higher scores indicate more anxiety. I simulated data by estimating factor loadings from Brattmyr et al. (2022).

- PHQ-9 (Kroenke et al., 2001) is a 9-item scale with Likert scaling ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Higher scores indicate higher levels of depression. I simulated data by estimating factor loadings from Brattmyr et al. (2022).

#Entering the intercorrelations, means, and standard deviations from the journal article

Szymanski_generating_model <- '

#measurement model

CollegeResponse =~ .88*cold + .73*unresponsive + .73*supportive

Stigma =~ .86*negative + .76*heterosexism + .71*harassed

Victimization =~ .8*Vic1 + .8*Vic2 + .8*Vic3 + .8*Vic4 + .8*Vic5 + .8*Vic6 + .8*Vic7 + .8*Vic8 + .8*Vic9

CollSat =~ .8*Sat1 + .8*Sat2 + .8*Sat3 + .8*Sat4 + .8*Sat5

Persistence =~ .69*graduation_importance + .63*right_decision + .62*will_register + .59*not_graduate + .45*undecided + .44*grades_unimportant

Anxiety =~ .851*nervous + .887*worry_control + .894*much_worry + 674*cant_relax + .484*restless + .442*irritable + 716*afraid

Depression =~ .798*anhedonia + .425*down + .591*sleep + .913*lo_energy + .441*appetite + .519*selfworth + .755*concentration + .454*too_slowfast + .695*s_ideation

#Means

CollegeResponse ~ 2.71*1

Stigma ~3.61*1

Victimization ~ 0.11*1

CollSat ~ 5.61*1

Persistence ~ 4.41*1

Anxiety ~ 1.45*1

Depression ~1.29*1

#Correlations

CollegeResponse ~~ .58*Stigma

CollegeResponse ~~ -.25*Victimization

CollegeResponse ~~ -.59*CollSat

CollegeResponse ~~ -.29*Persistence

CollegeResponse ~~ .17*Anxiety

CollegeResponse ~~ .18*Depression

Stigma ~~ .37*Victimization

Stigma ~~ -.41*CollSat

Stigma ~~ -.19*Persistence

Stigma ~~ .27*Anxiety

Stigma ~~ .24*Depression

Victimization ~~ -.22*CollSat

Victimization ~~ -.04*Persistence

Victimization ~~ .23*Anxiety

Victimization ~~ .21*Depression

CollSat ~~ .53*Persistence

CollSat ~~ -.29*Anxiety

CollSat ~~ -.32*Depression

Persistence ~~ -.22*Anxiety

Persistence ~~ -.26*Depression

Anxiety ~~ .76*Depression

'

set.seed(240218)

dfSzy <- lavaan::simulateData(model = Szymanski_generating_model,

model.type = "sem",

meanstructure = T,

sample.nobs=646,

standardized=FALSE)

#used to retrieve column indices used in the rescaling script below

col_index <- as.data.frame(colnames(dfSzy))

#The code below loops through each column of the dataframe and assigns the scaling accordingly

#Rows 1 thru 6 are the Perceptions of LGBTQ Campus Climate Scale

#Rows 7 thru 15 are the Sexual Orientation-Based Campus Victimization Scale

#Rows 16 thru 20 are the College Satisfaction Scale

#Rows 21 thru 26 are the Institutional and Goals Commitment Scale

#Rows 27 thru 33 are the GAD7

#Rows 34 thru 42 are the PHQ9

for(i in 1:ncol(dfSzy)){

if(i >= 1 & i <= 6){

dfSzy[,i] <- scales::rescale(dfSzy[,i], c(1, 7))

}

if(i >= 7 & i <= 15){

dfSzy[,i] <- scales::rescale(dfSzy[,i], c(0, 3))

}

if(i >= 16 & i <= 20){

dfSzy[,i] <- scales::rescale(dfSzy[,i], c(1, 7))

}

if(i >= 21 & i <= 26){

dfSzy[,i] <- scales::rescale(dfSzy[,i], c(1, 5))

}

if(i >= 27 & i <= 33){

dfSzy[,i] <- scales::rescale(dfSzy[,i], c(0, 3))

}

if(i >= 34 & i <= 42){

dfSzy[,i] <- scales::rescale(dfSzy[,i], c(0, 3))

}

}

#rounding to integers so that the data resembles that which was collected

library(tidyverse)

dfSzy <- dfSzy %>% round(0)

#quick check of my work

#psych::describe(dfSzy)

#Reversing the supportive item on the Perceptions of LGBTQ Campus Climate Scale so that the exercises will be consistent with the format in which the data was collected

dfSzy <- dfSzy %>%

dplyr::mutate(supportiveNR = 8 - supportive)

#Reversing three items on the Institutional and Goals Commitments scale so that the exercises will be consistent with the format in which the data was collected

dfSzy <- dfSzy %>%

dplyr::mutate(not_graduateNR = 8 - not_graduate)%>%

dplyr::mutate(undecidedNR = 8 - undecided)%>%

dplyr::mutate(grades_unimportantNR = 8 - grades_unimportant)

dfSzy <- dplyr::select(dfSzy, -c(supportive, not_graduate, undecided, grades_unimportant))The optional script below will let you save the simulated data to your computing environment as either an .rds object (preserves any formatting you might do) or a.csv file (think “Excel lite”).

# to save the df as an .rds (think 'R object') file on your computer;

# it should save in the same file as the .rmd file you are working

# with saveRDS(dfSzy, 'SzyDF.rds') bring back the simulated dat from

# an .rds file dfSzy <- readRDS('SzyDF.rds')# write the simulated data as a .csv write.table(dfSzy,

# file='SzyDF.csv', sep=',', col.names=TRUE, row.names=FALSE) bring

# back the simulated dat from a .csv file

dfSzy <- read.csv("SzyDF.csv", header = TRUE)As we move into the lecture, allow me to provide a content advisory. Individuals who hold LGBTQIA+ identities are frequently the recipients of discrimination and harassment. If you are curious about why these items are considered to be stigmatizing or non-responsive, please do not ask a member of the LGBTQIA+ community to explain it to you; it is not their job to educate others on discrimination, harassment, and microaggressions. Rather, please read the article in its entirety. Additionally, resources such as The Trevor Project, GLSEN, and Campus Pride are credible sources of information for learning more.

4.3 Fundamentals of Validity

Validity (the classic definition) is the ability of a test to measure what it purports to measure. Supporting that definition are these notions:

- Validity is extent of matching, congruence, or “goodness of fit” between the operational definition and concept it is supposed to measure.

- An instrument is said to be valid if it taps the concept it claims to measure.

- Validity is the appropriateness of the interpretation of the results of an assessment procedure for a given group of individuals, not to the procedure itself.

- Validity is a matter of degree; it does not exist on an all-or-none basis.

- Validity is always specific to some particular use or interpretation.

- Validity is a unitary concept.

- Validity involves an overall evaluative judgment.

Over the years (and, perhaps within each construct), validity has somewhat of an evolutionary path from a focus on content, to prediction, to theory and hypothesis testing.

When the focus is on content, we are concerned with the:

- Assessment of what individuals had learned in specific content areas.

- Relevance of its content (i.e., we compare the content to the content domain).

When the focus is on prediction, we are concerned with:

- How different persons respond in a given situation (now or later).

- The correlation coefficient between test scores (predictor) and the assessment of a criterion (performance in a situation)

A focus on theory and hypothesis testing adds:

- A strengthened theoretical orientation.

- A close linkage between psychological theory and verification through empirical and experimental hypothesis testing.

- An emphasis on constructs in describing and understanding human behavior.

Constructs are broad categories, derived from the common features shared by directly observable behavioral variables. They are theoretical entities and not directly observable. Construct validity is at the heart of psychometric evaluation. We define construct validity as the fundamental and all-inclusive validity concept, insofar as it specifies what the test measures. Content and predictive validation procedures are among the many sources of information that contribute to the understanding of the constructs assessed by a test.

4.4 Validity Criteria

We have just stated that validity is an overall, evaluative judgment. Within that umbrella are different criteria by which we judge the validity of a measure. We casually refer to them as types, but each speaks to that unitary concept.

4.4.1 Content Validity

Content validity is concerned with the representativeness of the domain being assessed. Content validation procedures may differ depending on whether the test is in the educational/achievement context or if it is more of an attitude/behavioral survey.

In the educational/achievement context, content validation seeks to ensure the items on an exam are appropriate for the content domain being assessed.

A table of specifications is a two-way chart which indicates the instructionally relevant learning tasks to be measured. Percentages in the table indicate the relative degree of emphasis that each content area.

Let’s imagine that I was creating a table of specifications for items on a quiz for this very chapter. The columns represent the types of outcomes we might expect. The American Psychological Association often talks about KSAs (knowledge, skills, attitudes), so I will utilize those as a framework. You’ll notice that the number of items and percentages do not align mathematically. Because, in the exam, I would likely weight application items (e.g., “work the problem”) more highly than knowledge items (e.g., multiple choice, true/false), the relative weighting may differ.

Table of Specifications

| Learning Objectives | Knowledge | Skills | Attitudes | % of test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distinguish between different types of validity based on short descriptions. | 6 items | 30% | ||

| Compute and interpret validity coefficients. | 2 items | 15% | ||

| Evaluate the incremental validity of an instrument-of-interest. | 1 item | 20% | ||

| Define and interpret the standard error of estimate. | 1 item | 15% | ||

| Develop a rationale that defends importance of establishing the validity of a measuring instrument. | 1 item | 20% | ||

| TOTALS | 7 items | 3 items | 1 item | 100% |

Subject matter experts (SMEs) are individuals chosen to evaluate items based on their degree of knowledge of the subject being assessed. If SMES are used, the researcher should:

- Report how many SMEs and list their professional qualifications.

- Report any directions the SMEs were given; if they were used to evaluate items, report the extent of agreement.

Empirical procedures for enhancing content validity of educational assessments may include:

- Comparing item-level and total scores with grades; lower grades should get lower scores.

- Analyzing individual errors.

- Observing student work methods (have the students “think aloud” in front of an examiner).

- Evaluating the role of speed, noting how many do not complete the test in the time allowed.

- Correlating the scores with a reading comprehension test (if the exam is highly correlated, then it may be a test of reading and not another subject). Alternatively, if it is a reading comprehension test, give the student the questions (without the passage) to see how well they answered the questions on the basis of prior knowledge.

For surveys and tests outside of educational settings, content validation procedures ask, “Does the test cover a representative sample of the specified skills and knowledge?” and “Is test performance reasonably free from the influence of irrelevant variables?” Naturally, SMEs might be used.

An example of content validation from Industrial-Organizational Psychology is the job analysis which precedes the development of test for employee selection and classification. Not all tests require content analysis. In aptitude and personality tests we are probably more interested in other types of validity evaluation.

4.4.2 Face Validity: The “Un”validity

Face validity is concerned with the question, “How does an assessment look on the ‘face of it’?” Let’s imagine that on a qualification exam for electricians, a math item asks the electrician to estimate the amount of yarn needed to complete a project. The item may be more face valid if the calculation was with wire. Thus, face validity can often be improved by reformulating test items in terms that appear relevant and plausible for the context.

Face validity should never be regarded as a substitute for objectively determined validity. In contrast, it should not be assumed that when a (valid and reliable) test has been modified to increase its face validity, that its objective validity and reliability is unaltered. That is, it should be reevaluated.

4.4.4 Construct Validity

Construct validity was introduced in 1954 in the first edition of APA’s testing standards and is defined as the extent to which the test may be said to measure a theoretical construct or trait. The overarching focus is on the role of psychological theory in test construction and the ability to formulate hypotheses that can be supported (or not) in the evaluation process. Construct validity is established by the accumulation of information from a variety of sources.

There are a number of sources that can be used to support construct validity.

4.4.5 Internal Consistency

In the next chapter, you will learn that internal consistency is generally considered to be an index of reliability. In the context of criterion-related validity, a goal is to ensure that the criterion is the total score on the test itself. To that end, some of the following could also support this aspect of validity:

- Comparing high and low scorers. Items that fail to show a significantly greater proportion of “passes” in the upper than the lower group are considered invalid and are modified or eliminated.

- Computing a biserial correlation between the item and total score.

- Correlating the subtest score with the total score. Any subtest whose correlation with the total score is too low is eliminated.

Although some take issue with this notion, the degree of homogeneity (the degree to which items assess the same thing) has some bearing on construct validity. There is a tradeoff between items that measure a narrow slice of the construct definition (internal consistency estimates are likely to be higher) and those that sample the construct definition more broadly (internal consistency estimates are likely to be lower).

Admittedly, the contribution of internal consistency data is limited. In absence of external data, it tells us little about WHAT the test measures.

4.4.6 Structural Validity

4.4.6.1 Exploratory Factor Analysis

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) is used to simplify the description of behavior by reducing the number of categories (factors or dimensions) to fewer than the number of items. In our research vignette the 6-item Perceptions of Campus Climate Scale will be represented by two factors (Szymanski & Bissonette, 2020) In instrument development, techniques like principal components analysis or principal axis factoring are used to identify clusters (latent factors) among items. We frequently treat these as scales and subscales.

Imagine the use of 20 tests to 300 people. There would be 190 correlations.

- Irrespective of content, we can probably summarize the intercorrelations of tests with 5-6 factors.

- When the clustering of tests includes vocabulary, analogies, opposites, and sentence completions, we might suggest a “verbal comprehension factor.”

- Factorial validity is the correlation of the test with whatever is common to a group of tests or other indices of behavior. If our single test has a correlation of .66 with the factor on which it loads, then the “factorial validity of the new test as a measure of the common trait is .66.”

When EFA is utilized, the items are “fed” into an iterative process that analyzes the relations and “reveals” (or suggests – we are the ones who interpret the data) how many factors (think scales/subscales) and which items comprise them.

4.4.6.2 Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) involves specifying, a priori, a proposed relationship of items, scales, and subscales and then testing its goodness of fit. In CFA (a form of structural equation modeling [SEM]), the latent variables (usually the higher order scales and total scale score) are positioned to cause the responses on the indicators/items.

Subsequent lessons provide examples of both EFA and CFA approaches to psychometrics.

4.4.7 Experimental Interventions

Construct validity is also supported by hypothesis testing and experimentation. If we expect that the construct assessed by the instrument is malleable (e.g., depression) and that an intervention could change it, then a random clinical trial that evaluated the effectiveness of an intervention (and it worked – depression scores declined) would simultaneously provide support for the intervention as well as the instrument.

4.4.8 Convergent and Discriminant Validity

In a psychometric evaluation, we will often administer our instrument-of-interest along with a battery of instruments that are more-and-less related. Convergent validity is supported when there are moderately high correlations between our tests and the instruments with which we expect moderately high correlations. In contrast, discriminant validity is established by low and/or non-significant correlations between our instrument-of-interest and instruments that should be unrelated. For example, we want a low and non-significant correlation between a quantitative reasoning test and scores on a reading comprehension test. Why? Because if the correlation is too high, the test cannot discriminate between reading comprehension and math.

There are no strict cut-offs to establish convergence or discrimination. We can even ask, “Could a correlation intended to support convergence be too high?” It is possible! Unless the instrument-of-interest offers advantages such as brevity or cost, then correlations that fall into the ranges of multicollinearity or singularity can indicate unnecessary duplication or redundancy.

In our research vignette, Szymanski and Bissonette (2020) conducted a correlation matrix that reports the bivariate relations between the LGBTQ Campus Climate full-scale as well as the College Response and Stigma subscales with measures that assess (a) LGBTQ victimization, (b) satisfaction with college, (c) persistence attitudes, and (d) anxiety, and (e) depression.

In order to produce this correlation matrix, we must first score each of the scales. In the items we prepared, the Perceptions of LGBTQ Campus Climate scale had one reverse-scored item. Similarly, the Institutional Goals and Commitments Scale had three reversed items. A first step in scoring is reversing these items.

The naming conventions that researchers use vary. I added an “NR” (for “needs reversing) to the original items so that I would remember to reverse-score them. I also am careful to reverse-score items into new variables. Otherwise, we risk getting confused about whether/not items are in their original or reversed formats.

Reverse-scoring the item is easily accomplished by subtracting the variable from “one plus” the scaling. Because both of these scales were on a 7-point scale, we will subtract the “NR” variables from 8.

# Reverse scoring the single item from the LGBTQ Campus Climate Scale

dfSzy <- dfSzy %>%

dplyr::mutate(unsupportive = 8 - supportiveNR)

# Reversing three items on the Institutional and Goals Commitments

# scale

dfSzy <- dfSzy %>%

dplyr::mutate(not_graduate = 8 - not_graduateNR) %>%

dplyr::mutate(undecided = 8 - undecidedNR) %>%

dplyr::mutate(grades_unimportant = 8 - grades_unimportantNR)Next, we create scale and/or subscale scores. The sjstats::mean_n() function allows us to specify how many items (whole number) or what percentage of items should be present in order to get the mean. It is customary to require 75-80% of items to be present for scoring. Three-item variables might allow one missing (i.e., 66%). In the code below, I first make lists of the variables that belong in each scale and subscale, then I create the new variables.

# Making the list of variables

LGBTQ_Climate <- c("cold", "unresponsive", "unsupportive", "negative",

"heterosexism", "harassed")

CollResponse <- c("cold", "unresponsive", "unsupportive")

Stigma <- c("negative", "heterosexism", "harassed")

Victimization <- c("Vic1", "Vic2", "Vic3", "Vic4", "Vic5", "Vic6", "Vic7",

"Vic8", "Vic9")

CampSat <- c("Sat1", "Sat2", "Sat3", "Sat4", "Sat5")

Persist <- c("graduation_importance", "right_decision", "will_register",

"not_graduate", "undecided", "grades_unimportant")

GAD7 <- c("nervous", "worry_control", "much_worry", "cant_relax", "restless",

"irritable", "afraid")

PHQ9 <- c("anhedonia", "down", "sleep", "lo_energy", "appetite", "selfworth",

"concentration", "too_slowfast", "s_ideation")

# Creating the new variables

dfSzy$LGBTQclimate <- sjstats::mean_n(dfSzy[, LGBTQ_Climate], 0.75)

dfSzy$CollegeRx <- sjstats::mean_n(dfSzy[, CollResponse], 0.66)

dfSzy$Stigma <- sjstats::mean_n(dfSzy[, Stigma], 0.66)

dfSzy$Victimization <- sjstats::mean_n(dfSzy[, Victimization], 0.8)

dfSzy$CampusSat <- sjstats::mean_n(dfSzy[, CampSat], 0.75)

dfSzy$Persistence <- sjstats::mean_n(dfSzy[, Persist], 0.8)

dfSzy$Anxiety <- sjstats::mean_n(dfSzy[, GAD7], 0.75)

dfSzy$Depression <- sjstats::mean_n(dfSzy[, PHQ9], 0.8)

# If the scoring code above does not work for you, try the format

# below which involves inserting to periods in front of the variable

# list. One example is provided. dfLewis$Belonging <-

# sjstats::mean_n(dfLewis[, ..Belonging_vars], 0.80)A correlation matrix of the scaled scores allows us to compare our scale(s) of interest to others within its nomological net.

apaTables::apa.cor.table(dfSzy[c("LGBTQclimate", "CollegeRx", "Stigma",

"Victimization", "CampusSat", "Persistence", "Anxiety", "Depression")],

filename = "SzyCor.doc", table.number = 1, show.sig.stars = TRUE, landscape = TRUE)

Table 1

Means, standard deviations, and correlations with confidence intervals

Variable M SD 1 2 3

1. LGBTQclimate 4.00 0.63

2. CollegeRx 4.04 0.77 .83**

[.81, .85]

3. Stigma 3.96 0.76 .83** .37**

[.80, .85] [.31, .44]

4. Victimization 1.55 0.33 .01 -.17** .20**

[-.06, .09] [-.25, -.10] [.13, .27]

5. CampusSat 4.24 0.70 -.49** -.46** -.35**

[-.55, -.43] [-.52, -.40] [-.41, -.28]

6. Persistence 3.03 0.42 -.21** -.17** -.17**

[-.28, -.13] [-.25, -.10] [-.25, -.10]

7. Anxiety 1.49 0.38 .17** .12** .17**

[.10, .25] [.04, .19] [.09, .24]

8. Depression 1.52 0.29 .18** .14** .15**

[.10, .25] [.07, .22] [.08, .23]

4 5 6 7

-.17**

[-.25, -.10]

-.04 .34**

[-.11, .04] [.27, .40]

.15** -.20** -.10*

[.07, .23] [-.28, -.13] [-.18, -.02]

.15** -.23** -.10** .54**

[.08, .23] [-.30, -.15] [-.18, -.03] [.48, .59]

Note. M and SD are used to represent mean and standard deviation, respectively.

Values in square brackets indicate the 95% confidence interval.

The confidence interval is a plausible range of population correlations

that could have caused the sample correlation (Cumming, 2014).

* indicates p < .05. ** indicates p < .01.

Examination of these values follow some expected patterns. First, the LGBTQ climate score (i.e., the total scale score) is highly correlated with each of its subscales (College Response r = .83, p < 0.01; Stigma r = .83, p = 0.01). These strong correlations are somewhat misleading because half of the items on the total scale are the same items on each of the subscales. The correlation between the two subscales is still statistically significant, but much lower (r = 0.37, p = 0.01).

Convergent and discriminant validity are of interest when we compare the LGBTQ Climate total scale score and the College Response and Stigma subscales with the additional measures. Regarding the total LGBTQ Climate score, a very strong correlation was observed with campus satisfaction (r = -0.49, p < 0.01); less strong correlations were observed with and persistence (r = -0.21, p < 0.01), anxiety (r = 0.17, p < 0.01), and depression (r = 0.18, p < 0.01). Recalling that higher scores on the LGBTQ Campus Climate score indicate a negative climate, we see that as the LGBTQ campus climate becomes increasingly stigmatizing and nonresponsive, students experience lower overall campus satisfaction and are less likely to persist at that institution. The correlation between LGBTQ Campus Climate and victimization was non-significant (r = 0.01, p > 0.05).

In assessing patterns of convergent and discriminant validity, the researcher would also take the time to map out the subscales (i.e., College Response, Stigma) with the additional measures.

4.4.8.1 Determining Statistically Significant Differences Between Correlations

Without a formal test, it is inappropriate for researchers to declare that one correlation is stronger than another. The package cocor allows the comparisons of dependent (i.e., all respondents are from the same sample) and independent (i.e., correlations are compared between two different samples) where the correlations themselves can be overlapping (i.e., with one common variable) or non-overlapping (i.e., the variables in both correlations are different).

Because all of the correlations we computed are within the same sample, they are dependent. When assessing convergent and discriminant validity it is common to ask if the correlations between the additional measures are different between the subscales of the focal measure. Results could support the notion that the subscales are related and yet different. An example of this might be comparing the correlations between victimization with the College Response subscale (r = -.17, p < 0.01) and victimization with Stigma subscale (r = 0.20, p < 0.01). This test would be overlapping because the victimization variable is in common. Here’s the code:

Results of a comparison of two overlapping correlations based on dependent groups

Comparison between r.jk (Victimization, CollegeRx) = -0.1741 and r.jh (Victimization, Stigma) = 0.2015

Difference: r.jk - r.jh = -0.3756

Related correlation: r.kh = 0.3734

Data: dfSzy: j = Victimization, k = CollegeRx, h = Stigma

Group size: n = 646

Null hypothesis: r.jk is equal to r.jh

Alternative hypothesis: r.jk is not equal to r.jh (two-sided)

Alpha: 0.05

pearson1898: Pearson and Filon's z (1898)

z = -8.9455, p-value = 0.0000

Null hypothesis rejected

hotelling1940: Hotelling's t (1940)

t = -9.0342, df = 643, p-value = 0.0000

Null hypothesis rejected

williams1959: Williams' t (1959)

t = -9.0340, df = 643, p-value = 0.0000

Null hypothesis rejected

olkin1967: Olkin's z (1967)

z = -8.9455, p-value = 0.0000

Null hypothesis rejected

dunn1969: Dunn and Clark's z (1969)

z = -8.7137, p-value = 0.0000

Null hypothesis rejected

hendrickson1970: Hendrickson, Stanley, and Hills' (1970) modification of Williams' t (1959)

t = -9.0341, df = 643, p-value = 0.0000

Null hypothesis rejected

steiger1980: Steiger's (1980) modification of Dunn and Clark's z (1969) using average correlations

z = -8.6124, p-value = 0.0000

Null hypothesis rejected

meng1992: Meng, Rosenthal, and Rubin's z (1992)

z = -8.5080, p-value = 0.0000

Null hypothesis rejected

95% confidence interval for r.jk - r.jh: -0.4678 -0.2926

Null hypothesis rejected (Interval does not include 0)

hittner2003: Hittner, May, and Silver's (2003) modification of Dunn and Clark's z (1969) using a backtransformed average Fisher's (1921) Z procedure

z = -8.6124, p-value = 0.0000

Null hypothesis rejected

zou2007: Zou's (2007) confidence interval

95% confidence interval for r.jk - r.jh: -0.4568 -0.2921

Null hypothesis rejected (Interval does not include 0)Fisher’s z-test (z = -8.6124, p < 0.001) tells us that the correlations are statistically significantly different from each other; Zhou’s confidence intervals provide the CI for the size of the difference between the two correlations. That is, the difference could be as large as -0.4568 or as small as -0.2921.

Another type of correlation comparison is with a the total and/or subscales, looking at the relative magnitude of their correlation with different variables. For example, we might wish to ask if the LGBTQ Campus Climate total scale is different degrees of correlation with anxiety (r = 0.17, p < 0.01) and depression (r = .18, p < 0.01).

Results of a comparison of two overlapping correlations based on dependent groups

Comparison between r.jk (LGBTQclimate, Anxiety) = 0.1724 and r.jh (LGBTQclimate, Depression) = 0.1795

Difference: r.jk - r.jh = -0.0071

Related correlation: r.kh = 0.5387

Data: dfSzy: j = LGBTQclimate, k = Anxiety, h = Depression

Group size: n = 646

Null hypothesis: r.jk is equal to r.jh

Alternative hypothesis: r.jk is not equal to r.jh (two-sided)

Alpha: 0.05

pearson1898: Pearson and Filon's z (1898)

z = -0.1914, p-value = 0.8482

Null hypothesis retained

hotelling1940: Hotelling's t (1940)

t = -0.1911, df = 643, p-value = 0.8485

Null hypothesis retained

williams1959: Williams' t (1959)

t = -0.1909, df = 643, p-value = 0.8487

Null hypothesis retained

olkin1967: Olkin's z (1967)

z = -0.1914, p-value = 0.8482

Null hypothesis retained

dunn1969: Dunn and Clark's z (1969)

z = -0.1909, p-value = 0.8486

Null hypothesis retained

hendrickson1970: Hendrickson, Stanley, and Hills' (1970) modification of Williams' t (1959)

t = -0.1911, df = 643, p-value = 0.8485

Null hypothesis retained

steiger1980: Steiger's (1980) modification of Dunn and Clark's z (1969) using average correlations

z = -0.1909, p-value = 0.8486

Null hypothesis retained

meng1992: Meng, Rosenthal, and Rubin's z (1992)

z = -0.1909, p-value = 0.8486

Null hypothesis retained

95% confidence interval for r.jk - r.jh: -0.0825 0.0678

Null hypothesis retained (Interval includes 0)

hittner2003: Hittner, May, and Silver's (2003) modification of Dunn and Clark's z (1969) using a backtransformed average Fisher's (1921) Z procedure

z = -0.1909, p-value = 0.8486

Null hypothesis retained

zou2007: Zou's (2007) confidence interval

95% confidence interval for r.jk - r.jh: -0.0798 0.0656

Null hypothesis retained (Interval includes 0)Fisher’s z-test (z = -0.1909, p = 0.8486) tells us that the correlations are not statistically significantly different from each other; Zhou’s confidence intervals indicate that the differences range between -0.0798 and 0.0656. Because this interval crosses zero, we know that the difference could be zero, or reversed in direction.

4.4.8.2 Multitrait-Multimethod Matrix

The multitrait-multimethod matrix is a systematic experimental design for the dual approach of convergent and discriminant validation, which requires the assessment of two or more traits (classically, math, English, and reading scores) by two more methods (self, parent, and teacher). Conducting a web-based image search on this term will show a matrix of alpha coefficients and correlation coefficients that are interpreted in relationship to each other. Roughly:

- alpha coefficients (internal consistency) should be the highest,

- validity coefficients (correlations of the same trait assessed by different methods) should be higher than correlations between different traits measured by different methods,

- validity coefficients (correlations of the same trait assessed by different methods) should be higher than different traits measured by the same method.

4.4.9 Incremental Validity

Incremental validity is the increase in predictive validity attributable to the test. It indicates the contribution the test makes to the selection of individuals who will meet the minimum standards in criterion performance. There are different ways to assess this – one of the most common is to first enter known predictors and then see if the instrument-of-interest continues to account variance over-and-above those that are entered.

In the Szymanski and Bissonette (2020) psychometric evaluation, the negative relations with satisfaction with college and intention to persist in college as well as positive relations with both anxiety and depression persisted even after controlling for LGBTQ victimization experiences.

I will demonstrate this procedure, predicting the contribution that the LGBTQ Campus Climate total scale score has on predicting intention to persist in college, over and above LGBTQ victimization.

The process is to use hierarchical linear regression. Two models are built. In the first mode (“PfV” stands [in my mind] for “Persistence from Victimization”), persistence is predicted from victimization. The second model adds the LGBTQ Campus Climate Scale. I asked for summaries of each model. Then the anova() function compares the model.

PfV <- lm(Persistence ~ Victimization, data = dfSzy)

PfVC <- lm(Persistence ~ Victimization + LGBTQclimate, data = dfSzy)

summary(PfV)

Call:

lm(formula = Persistence ~ Victimization, data = dfSzy)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-1.19281 -0.34150 -0.02281 0.29669 1.32226

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 3.09906 0.07947 38.997 <0.0000000000000002 ***

Victimization -0.04566 0.05023 -0.909 0.364

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 0.4224 on 644 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.001281, Adjusted R-squared: -0.0002694

F-statistic: 0.8263 on 1 and 644 DF, p-value: 0.3637From the PfV model we learn that victimization has a non-significant effect on intentions to persist in college (B = -0.046, p = 0.364). Further, the \(R^2\) is quite small (0.001).

Call:

lm(formula = Persistence ~ Victimization + LGBTQclimate, data = dfSzy)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-1.1696 -0.2842 0.0094 0.2569 1.3571

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 3.64440 0.12795 28.483 < 0.0000000000000002 ***

Victimization -0.04183 0.04919 -0.850 0.395

LGBTQclimate -0.13788 0.02568 -5.369 0.000000111 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 0.4135 on 643 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.04413, Adjusted R-squared: 0.04116

F-statistic: 14.84 on 2 and 643 DF, p-value: 0.0000004991In the PfVC model, we see that the LGBTQ Campus Climate full scale score has a significant impact on intentions to persist. Specifically, for each additional point higher on the LGBTQ climate score, intentions to persist decrease by .14 points (p < 0.001). Together, the model accounts for 4% of the variance, representing a \(\Delta{R^2}\) of 4%.

[1] 0.042849Analysis of Variance Table

Model 1: Persistence ~ Victimization

Model 2: Persistence ~ Victimization + LGBTQclimate

Res.Df RSS Df Sum of Sq F Pr(>F)

1 644 114.88

2 643 109.95 1 4.929 28.824 0.0000001108 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1We see that there is a statistically significant difference between the models \(F(1, 643) = 28.824, p < 0.001)\).

Let’s try another model. With anxiety as our dependent variable, the code below asks if LGBTQ Campus Climate accounts for a proportion of the variance over-and-above victimization.

AfV <- lm(Anxiety ~ Victimization, data = dfSzy)

AfVC <- lm(Anxiety ~ Victimization + LGBTQclimate, data = dfSzy)

summary(AfV)

Call:

lm(formula = Anxiety ~ Victimization, data = dfSzy)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-1.05943 -0.30935 -0.01528 0.31306 1.24148

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 1.21756 0.07131 17.073 < 0.0000000000000002 ***

Victimization 0.17427 0.04508 3.866 0.000122 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 0.379 on 644 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.02268, Adjusted R-squared: 0.02116

F-statistic: 14.95 on 1 and 644 DF, p-value: 0.0001219

Call:

lm(formula = Anxiety ~ Victimization + LGBTQclimate, data = dfSzy)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-1.00814 -0.29249 -0.02563 0.29877 1.20705

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 0.81071 0.11561 7.012 0.00000000000595 ***

Victimization 0.17141 0.04444 3.857 0.000126 ***

LGBTQclimate 0.10287 0.02320 4.433 0.00001092659570 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 0.3736 on 643 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.05166, Adjusted R-squared: 0.04872

F-statistic: 17.52 on 2 and 643 DF, p-value: 0.0000000392Analysis of Variance Table

Model 1: Anxiety ~ Victimization

Model 2: Anxiety ~ Victimization + LGBTQclimate

Res.Df RSS Df Sum of Sq F Pr(>F)

1 644 92.513

2 643 89.770 1 2.7436 19.651 0.00001093 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1This model is a little more exciting in that our first model (AfV) is statistically significant \((B = 0.174, p < 0.001)\). That is, victimization has a statistically significant effect on anxiety, accounting for 2% of the variance. In the second model, the LGBTQ Campus Climate total scale score is also significant \((B = 0.103, p < 0.001)\), and accounts for an additional 3% of variance (\(\Delta{R^2} = 0.029\). There is a statistically significant difference between models (F[1, 643] = 19.651, p < .001).

[1] 0.028984.5 Factors Affecting Validity Coefficients

Keeping in mind that a validity coefficient is merely the correlation between the test and some criteria, the same elements that impact the magnitude and significance of a correlation coefficient will similarly affect a validity coefficient.

Nature of the group. A test that has high validity in predicting a particular criterion in one population, may have little or no validity in predicting the same criterion in another population. If a test is designed for use in diverse populations, information about the population generalizability should be reported in the technical manuals.

Sample heterogeneity. Other things being equal, if there is a linear relationship between X and Y, it will have a greater magnitude when the sample is heterogeneous.

Pre-selection. Just like internal and external validity in a research design can be threatened by selection issues, pre-selection can also impact the validity coefficients of a measure. For example, if we are evaluating a new test for job selection, we may select a group of newly hired employees. We plan to collect some measure of job performance at a later date. Our results may be limited by the criteria used to select the employees. Were they volunteers? Were they only those hired? Were they ALL of the applicants?

Validity coefficients may change over time. Consider the relationship between the college boards and grade point average at Yale University. Fifty years ago, \(r_{xy} = .72\); today \(r_{xy} = .52\). Why? The nature of the student body has become more diverse (50 years ago, the student body was predominantly White, high SES, and male).

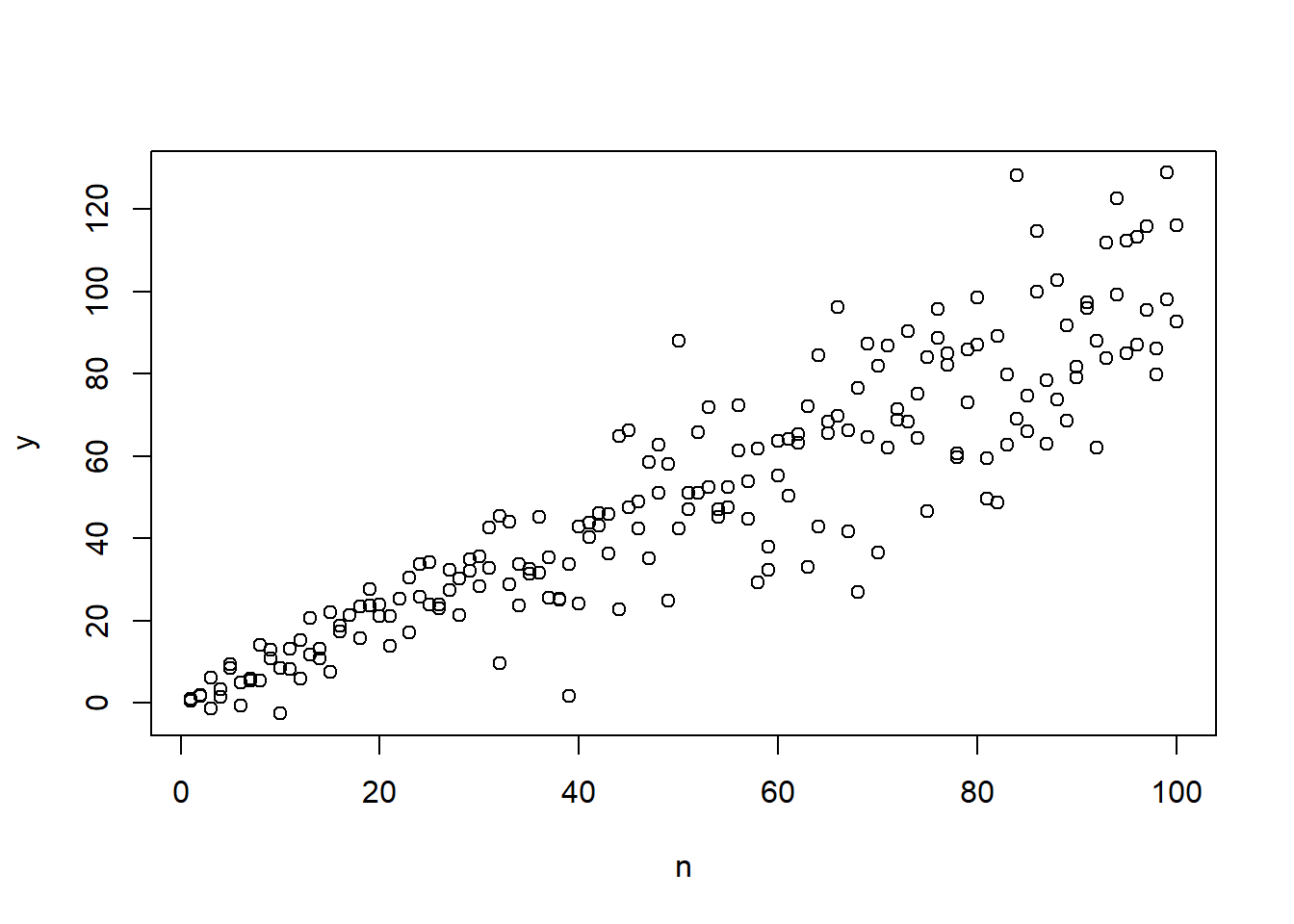

The form of the relationship matters. The Pearson R assumes the relationship between the predictor and criterion variables is linear, uniform, and homoscedastistic (equal variability throughout the range of a bivariate distribution). When the variability is unequal throughout the range of the distribution the relationship is heteroscedastic.

Figure 4.1: Illustration of heteroscedasticity

There could also be other factors involved in the relationship between the instrument and the criterion:

- curvilinearity

- an undetected mechanism, such as a moderator

Finally, what is our threshold for acceptability?

- Consider statistical significance – but also its limitations (e.g., power, Type I error, Type II error)

- Consider the magnitude of the correlation; and also \(R^2\) (the proportion of variance accounted for)

- Consider error:

- The standard error of the estimate shows the margin of error to be expected in the individuals predicted criterion score as the result of the imperfect validity of the instrument.

\[SE_{est} = SD_{y}\sqrt{1 - r_{xy}^{2}}\] Where:

- \(r_{xy}^{2}\) is the square of the validity coefficient, and

- \(SD_{y}\) is the standard deviation of the criterion scores.

If the validity were perfect (\(r_{xy}^{2}\) = 1.00), the error of estimate would be 0.00. If the validity were zero, the error of estimate would equal \(SD_{y}\).

Interpreting \(SE_{est}\):

- If \(r_{xy}\) = .80, then \(\sqrt{1 - r_{xy}^{2}} = .60\).

- Error is 60% as large as it would be by chance. Stated another way, predicting an individual’s criterion performance has a margin of error that is 40% smaller than it would be by chance.

To obtain the \(SE_{est}\), we merely multiply by the \(SD_{y}\). This puts error in the metric of the criterion variable.

Your Turn:

- If \(r_{xy}\) = .25, then \(\sqrt{1 - r_{xy}^{2}} =\) ??

Make a statement about chance. Make a statement about margin of error.

4.6 Practice Problems

In each of these lessons, I provide suggestions for practice that allow you to select one or more problems that are graded in difficulty. With each of these options, I encourage you to interpret examine aspects of the construct validity through the creation and interpretation of validity coefficients. Ideally, you will examine both convergent/discriminant validity as well as incremental validity.

4.6.1 Problem #1: Play around with this simulation.

Copy the script for the simulation and then change (at least) one thing in the simulation to see how it impacts the results.

If calculating is new to you, perhaps you just change the number in “set.seed(210907)” from 210907 to something else. Your results should parallel those obtained in the lecture, making it easier for you to check your work as you go.

4.6.2 Problem #2: Conduct the reliability analysis selecting different variables.

The Szymanski and Bissonette (2020) article conducted a handful of incremental validity assessments. Select different outcome variables (e.g., depression) and/or use the subscales as the instrument-of-interest.

4.6.3 Problem #3: Try something entirely new.

Using data for which you have permission and access (e.g., IRB approved data you have collected or from your lab; data you simulate from a published article; data from an open science repository; data from other chapters in this OER), create validity coefficients and use three variables to estimate the incremental validity of the instrument-of-interest.

4.6.4 Grading Rubric

| Assignment Component | Points Possible | Points Earned |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Check and, if needed, format and score the data. | 5 | _____ |

| 2. Create a correlation matrix that includes the instrument-of-interest and the variables that will have varying degrees of relation. | 5 | _____ |

| 3. With convergent and discriminant validity in mind, interpret the validity coefficients; this should include an assessment about whether the correlation coefficients (at least two different pairings) are statistically significantly different from each other. | 5 | _____ |

| 4. With at least three variables, evaluate the degree to which the instrument demonstrates incremental validity (this should involve two regression equations and their statistical comparison). | 5 | _____ |

| 5. Explanation to grader. | 5 | _____ |

| Totals | 25 | _____ |

4.7 Homeworked Example

For more information about the data used in this homeworked example, please refer to the description and codebook located at the end of the introduction in first volume of ReCentering Psych Stats.

As a brief review, this data is part of an IRB-approved study, with consent to use in teaching demonstrations and to be made available to the general public via the open science framework. Hence, it is appropriate to use in this context. You will notice there are student- and teacher- IDs. These numbers are not actual student and teacher IDs, rather they were further re-identified so that they could not be connected to actual people.

Because this is an actual dataset, if you wish to work the problem along with me, you will need to download the ReC.rds data file from the Worked_Examples folder in the ReC_Psychometrics project on the GitHub.

The course evaluation items can be divided into three subscales:

- Valued by the student includes the items: ValObjectives, IncrUnderstanding, IncrInterest

- Traditional pedagogy includes the items: ClearResponsibilities, EffectiveAnswers, Feedback, ClearOrganization, ClearPresentation

- Socially responsive pedagogy includes the items: InclusvClassrm, EquitableEval, MultPerspectives, DEIintegration

In this homework focused on validity we will score the total scale and subscales, create a correlation matrix of our scales with a different scale (or item), formally test to see if correlation coefficients are statistically significantly different from each other, conduct a test of incremental validity.

4.7.1 Check and, if needed, format data

Let’s check the structure…

Classes 'data.table' and 'data.frame': 310 obs. of 33 variables:

$ deID : int 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 ...

$ CourseID : int 57085635 57085635 57085635 57085635 57085635 57085635 57085635 57085635 57085635 57085635 ...

$ Dept : chr "CPY" "CPY" "CPY" "CPY" ...

$ Course : Factor w/ 3 levels "Psychometrics",..: 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 ...

$ StatsPkg : Factor w/ 2 levels "SPSS","R": 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 ...

$ Centering : Factor w/ 2 levels "Pre","Re": 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 ...

$ Year : int 2021 2021 2021 2021 2021 2021 2021 2021 2021 2021 ...

$ Quarter : chr "Fall" "Fall" "Fall" "Fall" ...

$ IncrInterest : int 5 3 4 2 4 3 5 3 2 5 ...

$ IncrUnderstanding : int 2 3 4 3 4 4 5 2 4 5 ...

$ ValObjectives : int 5 5 4 4 5 5 5 5 4 5 ...

$ ApprAssignments : int 5 4 4 4 5 3 5 3 3 5 ...

$ EffectiveAnswers : int 5 3 5 3 5 3 4 3 2 3 ...

$ Respectful : int 5 5 4 5 5 4 5 4 5 5 ...

$ ClearResponsibilities : int 5 5 4 4 5 4 5 4 4 5 ...

$ Feedback : int 5 3 4 2 5 NA 5 4 4 5 ...

$ OvInstructor : int 5 4 4 3 5 3 5 4 3 5 ...

$ MultPerspectives : int 5 5 4 5 5 4 5 5 5 5 ...

$ OvCourse : int 3 4 4 3 5 3 5 3 2 5 ...

$ InclusvClassrm : int 5 5 5 5 5 4 5 5 4 5 ...

$ DEIintegration : int 5 5 5 5 5 4 5 5 5 5 ...

$ ClearPresentation : int 4 4 4 2 5 3 4 4 4 5 ...

$ ApprWorkload : int 5 5 3 4 4 2 5 4 4 5 ...

$ MyContribution : int 4 4 4 4 5 4 4 3 4 5 ...

$ InspiredInterest : int 5 3 4 3 5 3 5 4 4 5 ...

$ Faith : int 5 NA 4 2 NA NA 4 4 4 NA ...

$ EquitableEval : int 5 5 3 5 5 3 5 5 3 5 ...

$ SPFC.Decolonize.Opt.Out: chr "" "" "" "" ...

$ ProgramYear : Factor w/ 3 levels "Second","Transition",..: 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 ...

$ ClearOrganization : int 3 4 3 4 4 4 5 4 4 5 ...

$ RegPrepare : int 5 4 4 4 4 3 4 4 4 5 ...

$ EffectiveLearning : int 2 4 3 4 4 2 5 3 2 5 ...

$ AccessibleInstructor : int 5 4 4 4 5 4 5 4 5 5 ...

- attr(*, ".internal.selfref")=<externalptr> We will need to create the three subscales. The codebook above, lists which variables go in each subscale score.

# Making the list of variables

ValuedVars <- c("ValObjectives", "IncrUnderstanding", "IncrInterest")

TradPedVars <- c("ClearResponsibilities", "EffectiveAnswers", "Feedback",

"ClearOrganization", "ClearPresentation")

SRPedVars <- c("InclusvClassrm", "EquitableEval", "MultPerspectives", "DEIintegration")

Total <- c("ValObjectives", "IncrUnderstanding", "IncrInterest", "ClearResponsibilities",

"EffectiveAnswers", "Feedback", "ClearOrganization", "ClearPresentation",

"InclusvClassrm", "EquitableEval", "MultPerspectives", "DEIintegration")

# Creating the new variables

big$Valued <- sjstats::mean_n(big[, ValuedVars], 0.66)

big$TradPed <- sjstats::mean_n(big[, TradPedVars], 0.75)

big$SRPed <- sjstats::mean_n(big[, SRPedVars], 0.75)

big$Total <- sjstats::mean_n(big[, Total], 0.8)

# If the scoring code above does not work for you, try the format

# below which involves inserting to periods in front of the variable

# list. One example is provided. dfLewis$Belonging <-

# sjstats::mean_n(dfLewis[, ..Belonging_vars], 0.80)4.7.2 Create a correlation matrix that includes the instrument-of-interest and the variables that will have varying degrees of relation

Unfortunately, data from the course evals don’t include any outside scales. However, I didn’t include the “Overall Instructor” (OvInstructor) in any of the items, so we could think of it as a way to look at convergent and discriminant validity.

apaTables::apa.cor.table(big[c("Valued", "TradPed", "SRPed", "OvInstructor")],

filename = "ReC_cortable.doc", table.number = 1, show.sig.stars = TRUE,

landscape = TRUE)

Table 1

Means, standard deviations, and correlations with confidence intervals

Variable M SD 1 2 3

1. Valued 4.25 0.68

2. TradPed 4.25 0.76 .70**

[.63, .75]

3. SRPed 4.52 0.58 .56** .71**

[.48, .64] [.65, .76]

4. OvInstructor 4.37 0.94 .63** .80** .67**

[.56, .70] [.76, .84] [.60, .73]

Note. M and SD are used to represent mean and standard deviation, respectively.

Values in square brackets indicate the 95% confidence interval.

The confidence interval is a plausible range of population correlations

that could have caused the sample correlation (Cumming, 2014).

* indicates p < .05. ** indicates p < .01.

All the correlations are strong and positive. However, look at the correlation between Overall Instructor and SCRPed!

4.7.3 With convergent and discriminant validity in mind, interpret the validity coefficients; this should include an assessment about whether the correlation coefficients (at least two different pairings) are statistically significantly different from each other.

We need to see if these correlations are statistically significantly different from each other. I am interested in knowing if the correlations between Overall Instructor and each of the three course dimensions (Valued [r = 0.63, p < 0.01], TradPed [r = 0.80, p < 0.01], SRPed [r = 0.67, p < 0.01]) are statistically significantly different from each other.

Results of a comparison of two overlapping correlations based on dependent groups

Comparison between r.jk (OvInstructor, Valued) = 0.6344 and r.jh (OvInstructor, TradPed) = 0.7997

Difference: r.jk - r.jh = -0.1652

Related correlation: r.kh = 0.697

Data: big: j = OvInstructor, k = Valued, h = TradPed

Group size: n = 307

Null hypothesis: r.jk is equal to r.jh

Alternative hypothesis: r.jk is not equal to r.jh (two-sided)

Alpha: 0.05

pearson1898: Pearson and Filon's z (1898)

z = -5.4939, p-value = 0.0000

Null hypothesis rejected

hotelling1940: Hotelling's t (1940)

t = -6.2651, df = 304, p-value = 0.0000

Null hypothesis rejected

williams1959: Williams' t (1959)

t = -6.1447, df = 304, p-value = 0.0000

Null hypothesis rejected

olkin1967: Olkin's z (1967)

z = -5.4939, p-value = 0.0000

Null hypothesis rejected

dunn1969: Dunn and Clark's z (1969)

z = -5.9983, p-value = 0.0000

Null hypothesis rejected

hendrickson1970: Hendrickson, Stanley, and Hills' (1970) modification of Williams' t (1959)

t = -6.2651, df = 304, p-value = 0.0000

Null hypothesis rejected

steiger1980: Steiger's (1980) modification of Dunn and Clark's z (1969) using average correlations

z = -5.9444, p-value = 0.0000

Null hypothesis rejected

meng1992: Meng, Rosenthal, and Rubin's z (1992)

z = -5.9182, p-value = 0.0000

Null hypothesis rejected

95% confidence interval for r.jk - r.jh: -0.4644 -0.2333

Null hypothesis rejected (Interval does not include 0)

hittner2003: Hittner, May, and Silver's (2003) modification of Dunn and Clark's z (1969) using a backtransformed average Fisher's (1921) Z procedure

z = -5.8868, p-value = 0.0000

Null hypothesis rejected

zou2007: Zou's (2007) confidence interval

95% confidence interval for r.jk - r.jh: -0.2282 -0.1089

Null hypothesis rejected (Interval does not include 0)Fisher’s z-test (z = -5.887, p < 0.001) indicates that the correlation of overall instructor with the valued subscale (r = 0.63) is lower than its correlation with the traditional pedagogy subscale (r = 0.80).

Results of a comparison of two overlapping correlations based on dependent groups

Comparison between r.jk (OvInstructor, TradPed) = 0.7962 and r.jh (OvInstructor, SRPed) = 0.6751

Difference: r.jk - r.jh = 0.1211

Related correlation: r.kh = 0.7091

Data: big: j = OvInstructor, k = TradPed, h = SRPed

Group size: n = 298

Null hypothesis: r.jk is equal to r.jh

Alternative hypothesis: r.jk is not equal to r.jh (two-sided)

Alpha: 0.05

pearson1898: Pearson and Filon's z (1898)

z = 4.2785, p-value = 0.0000

Null hypothesis rejected

hotelling1940: Hotelling's t (1940)

t = 4.6684, df = 295, p-value = 0.0000

Null hypothesis rejected

williams1959: Williams' t (1959)

t = 4.5800, df = 295, p-value = 0.0000

Null hypothesis rejected

olkin1967: Olkin's z (1967)

z = 4.2785, p-value = 0.0000

Null hypothesis rejected

dunn1969: Dunn and Clark's z (1969)

z = 4.5174, p-value = 0.0000

Null hypothesis rejected

hendrickson1970: Hendrickson, Stanley, and Hills' (1970) modification of Williams' t (1959)

t = 4.6684, df = 295, p-value = 0.0000

Null hypothesis rejected

steiger1980: Steiger's (1980) modification of Dunn and Clark's z (1969) using average correlations

z = 4.4945, p-value = 0.0000

Null hypothesis rejected

meng1992: Meng, Rosenthal, and Rubin's z (1992)

z = 4.4834, p-value = 0.0000

Null hypothesis rejected

95% confidence interval for r.jk - r.jh: 0.1510 0.3855

Null hypothesis rejected (Interval does not include 0)

hittner2003: Hittner, May, and Silver's (2003) modification of Dunn and Clark's z (1969) using a backtransformed average Fisher's (1921) Z procedure

z = 4.4678, p-value = 0.0000

Null hypothesis rejected

zou2007: Zou's (2007) confidence interval

95% confidence interval for r.jk - r.jh: 0.0676 0.1802

Null hypothesis rejected (Interval does not include 0)Fisher’s z-test (z = 4.4678, p < 0.001) indicates that the correlation of overall instructor with the traditional pedagogy subscale (r = 0.80) is higher than its correlation with the socially responsive pedagogy subscale (r = 0.67).

Results of a comparison of two overlapping correlations based on dependent groups

Comparison between r.jk (OvInstructor, Valued) = 0.6338 and r.jh (OvInstructor, SRPed) = 0.6717

Difference: r.jk - r.jh = -0.0379

Related correlation: r.kh = 0.5624

Data: big: j = OvInstructor, k = Valued, h = SRPed

Group size: n = 299

Null hypothesis: r.jk is equal to r.jh

Alternative hypothesis: r.jk is not equal to r.jh (two-sided)

Alpha: 0.05

pearson1898: Pearson and Filon's z (1898)

z = -1.0091, p-value = 0.3129

Null hypothesis retained

hotelling1940: Hotelling's t (1940)

t = -1.0355, df = 296, p-value = 0.3013

Null hypothesis retained

williams1959: Williams' t (1959)

t = -1.0071, df = 296, p-value = 0.3147

Null hypothesis retained

olkin1967: Olkin's z (1967)

z = -1.0091, p-value = 0.3129

Null hypothesis retained

dunn1969: Dunn and Clark's z (1969)

z = -1.0062, p-value = 0.3143

Null hypothesis retained

hendrickson1970: Hendrickson, Stanley, and Hills' (1970) modification of Williams' t (1959)

t = -1.0355, df = 296, p-value = 0.3013

Null hypothesis retained

steiger1980: Steiger's (1980) modification of Dunn and Clark's z (1969) using average correlations

z = -1.0060, p-value = 0.3144

Null hypothesis retained

meng1992: Meng, Rosenthal, and Rubin's z (1992)

z = -1.0058, p-value = 0.3145

Null hypothesis retained

95% confidence interval for r.jk - r.jh: -0.1948 0.0627

Null hypothesis retained (Interval includes 0)

hittner2003: Hittner, May, and Silver's (2003) modification of Dunn and Clark's z (1969) using a backtransformed average Fisher's (1921) Z procedure

z = -1.0058, p-value = 0.3145

Null hypothesis retained

zou2007: Zou's (2007) confidence interval

95% confidence interval for r.jk - r.jh: -0.1129 0.0360

Null hypothesis retained (Interval includes 0)Fisher’s z-test (z = -1.006, p = 0.315) indicates that the correlation of overall instructor with the valued subscale (r = 0.4) is not statistically significantly different than its correlation with the socially responsive pedagogy subscale (r = 0.67).

4.7.4 With at least three variables, evaluate the degree to which the instrument demonstrates incremental validity (this should involve two regression equations and their statistical comparison)

Playing around with these variables, let’s presume our outcome of interested is the student’s valuation of the class (i.e., the “Valued by the Student variable”) and we usually predict it through traditional pedagogy. What does SRPed contribute over-and-above?

Please understand, that we would normally have a more robust dataset with other indicators – maybe predicting students’ grades?

Also, we are completely ignoring the multi-level nature of this data. The published manuscript takes a multi-level approach to analyzing the data and my lessons on multi-level modeling address this as well.

big <- na.omit(big) #included b/c there was uneven missingness and the subsequent comparison required equal sample sizes in the regression models

Step1 <- lm(Valued ~ TradPed, data = big)

Step2 <- lm(Valued ~ TradPed + SRPed, data = big)

summary(Step1)

Call:

lm(formula = Valued ~ TradPed, data = big)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-1.43330 -0.25471 0.04673 0.25388 1.79522

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 1.67482 0.18581 9.014 <0.0000000000000002 ***

TradPed 0.61426 0.04191 14.656 <0.0000000000000002 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 0.4274 on 213 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.5021, Adjusted R-squared: 0.4998

F-statistic: 214.8 on 1 and 213 DF, p-value: < 0.00000000000000022

Call:

lm(formula = Valued ~ TradPed + SRPed, data = big)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-1.39671 -0.22675 0.03228 0.24841 1.71917

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 1.44912 0.26349 5.500 0.000000109 ***

TradPed 0.56933 0.05602 10.162 < 0.0000000000000002 ***

SRPed 0.09116 0.07554 1.207 0.229

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 0.427 on 212 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.5055, Adjusted R-squared: 0.5009

F-statistic: 108.4 on 2 and 212 DF, p-value: < 0.00000000000000022In the first step we see that traditional pedagogy had a statistically significant effect on the valued dimension \(B = 0.614, p < 0.001)\). This model accounted for 50% of variance.

In the second step, socially responsive pedagogy was not a statistically significant predictor, over and above traditional pedagogy \(B = 0.091, p = 0.228\). This model accounted for 51% of variance.

We can formally compare these two models with an the anova() function in base R.

Analysis of Variance Table

Model 1: Valued ~ TradPed

Model 2: Valued ~ TradPed + SRPed

Res.Df RSS Df Sum of Sq F Pr(>F)

1 213 38.918

2 212 38.652 1 0.26554 1.4564 0.2288We see that socially responsive pedagogy adds only a non-significant proportion of variance over traditional pedagogy \((F[1, 212] = 38.652, p = 0.229)\).