Chapter 8 Factorial (Between-Subjects) ANOVA

In this (somewhat long and complex) lesson we conduct a 3X2 ANOVA. We will

- Work an actual example from the literature.

- “by hand”, and

- with R packages

- I will also demonstrate

- several options for exploring interaction effects, and

- several options for exploring main effects.

- Exploring these options will allow us to:

- Gain familiarity with the concepts central to multi-factor ANOVAs.

- Explore tools for analyzing the complexity in designs.

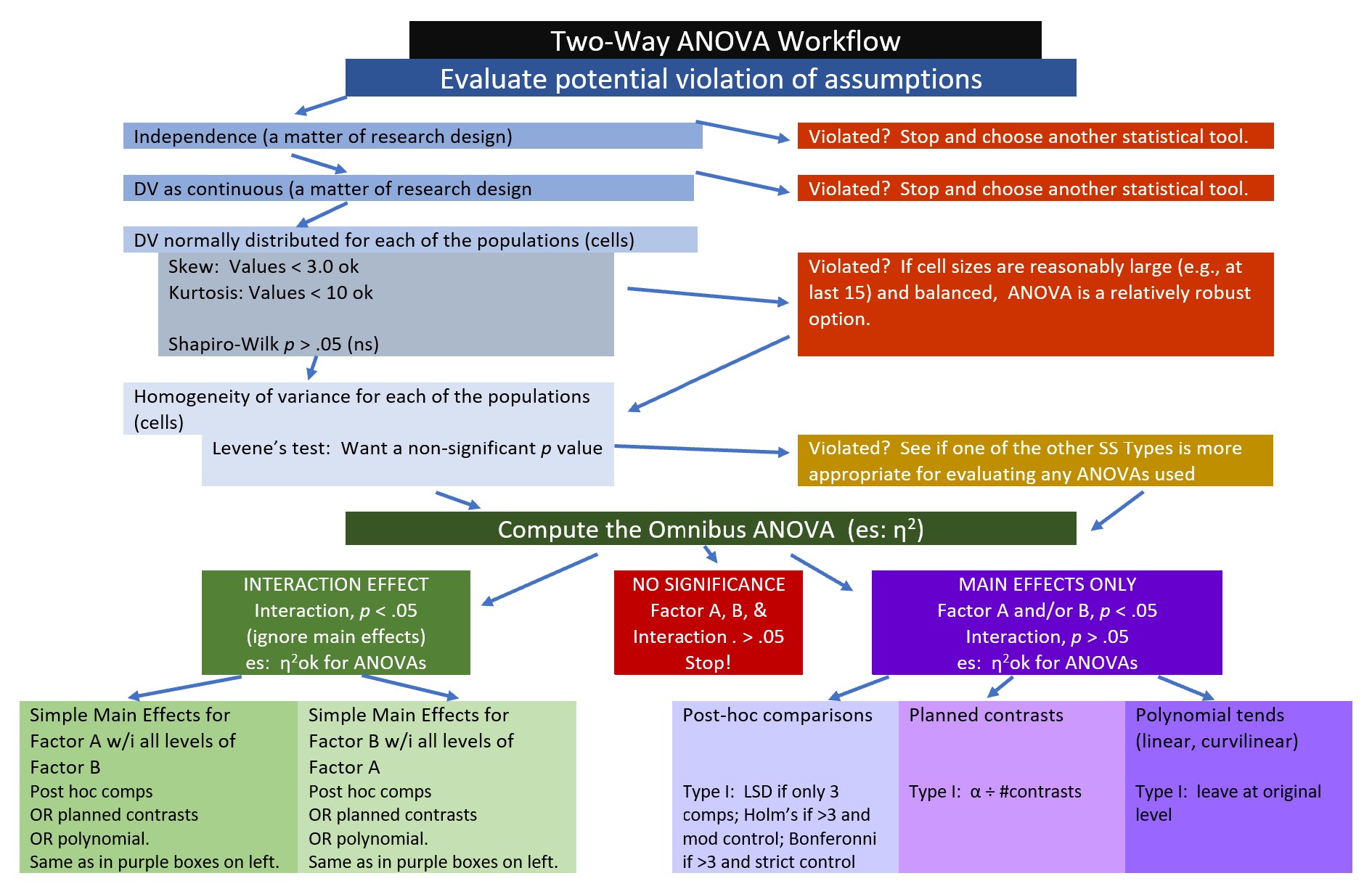

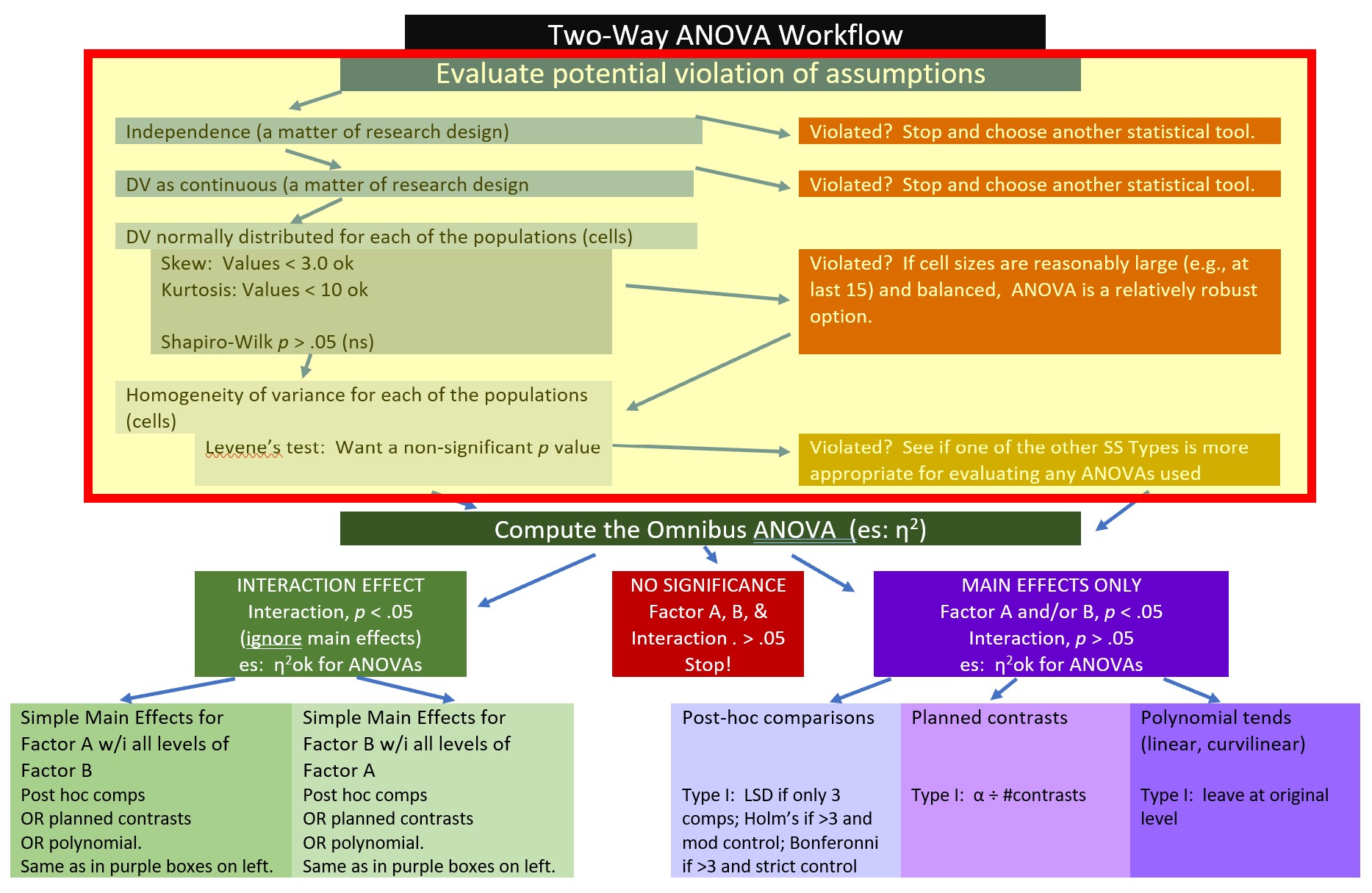

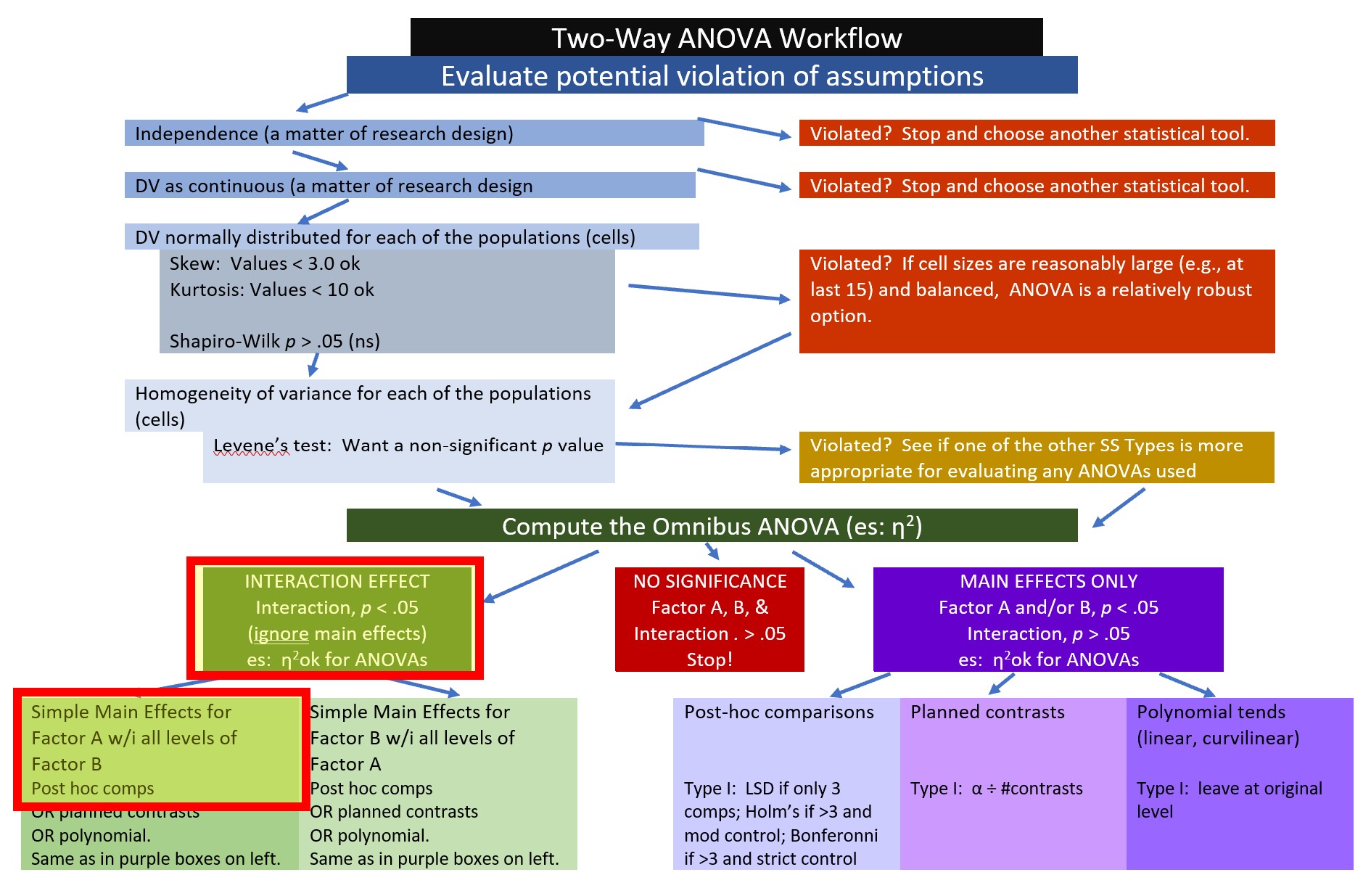

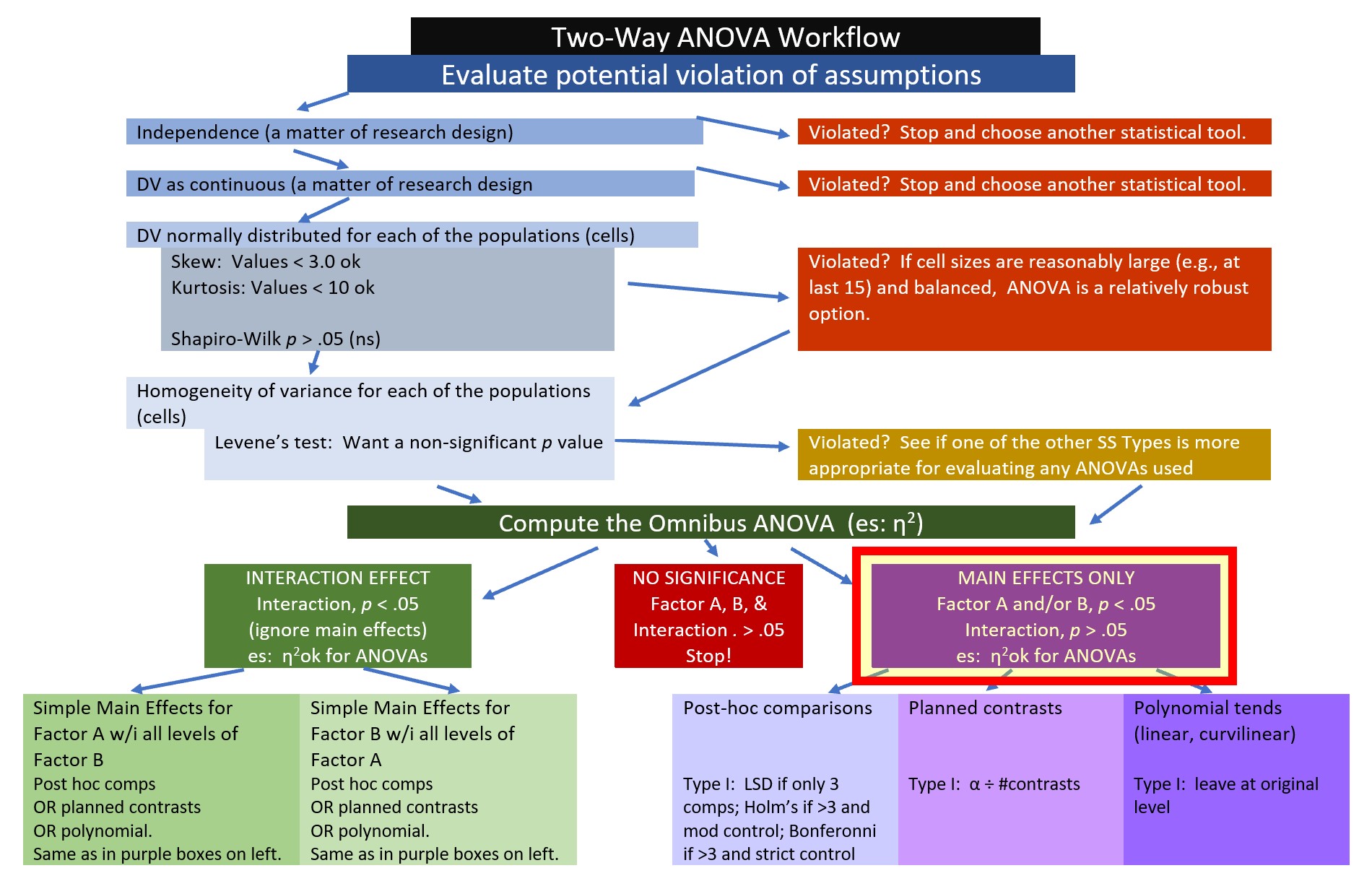

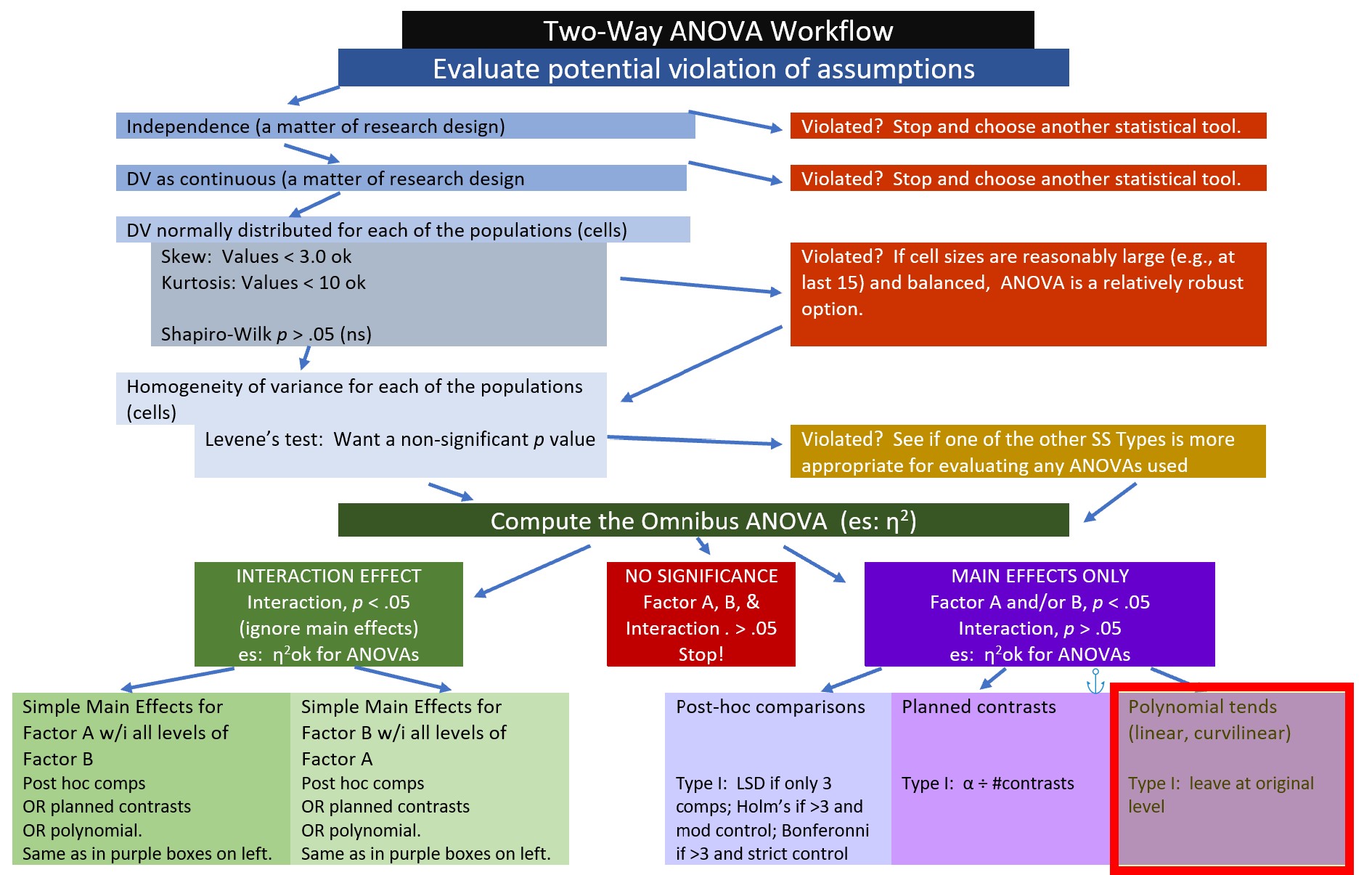

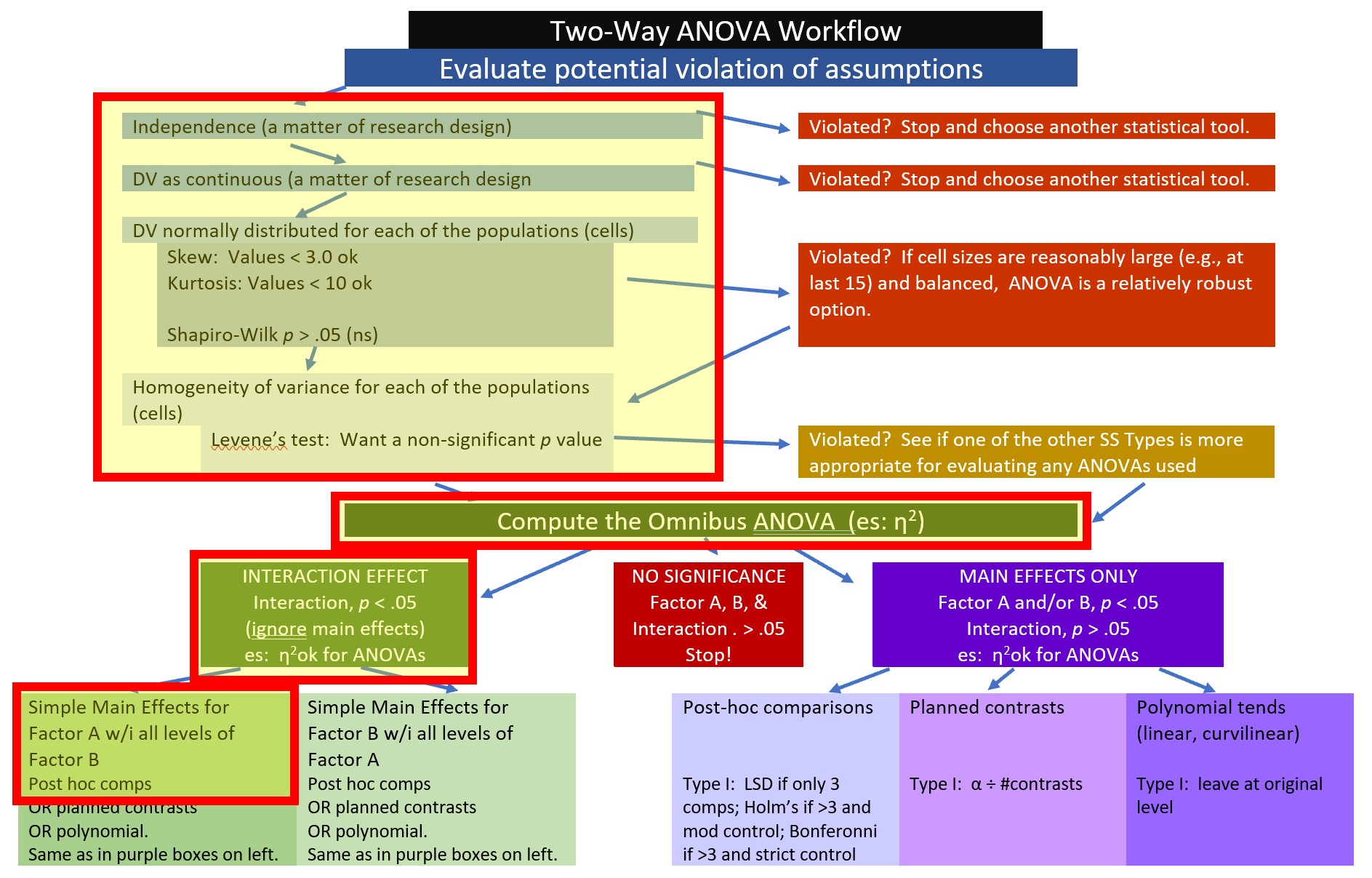

The complexity is that not all of these things need to be conducted for every analysis. The two-way ANOVA Workflow is provided to help you map a way through your own analyses. I will periodically refer to this map so that we can more easily keep track of where we are in the process.

8.2 Introducing Factorial ANOVA

My approach to teaching is to address the conceptual as we work problems. That said, there are some critical ideas we should address first.

ANOVA is for experiments (or arguably closely related designs). As we learn about the assumptions you’ll see that ANOVA has some rather restrictive ones (e.g., there should be an equal/equivalent number of cases per cell). To the degree that we violate these assumptions, we should locate alternative statistical approaches where these assumptions are relaxed.

Factorial: a term used when there are two or more independent variables (IVs; the factors). The factors could be between-groups, within-groups, repeated measures, or a combination of between and within.

- Independent factorial design: several IVs (predictors/factors) and each has been measured using different participants (between groups).

- Related factorial design: several IVs (factors/predictors) have been measured, but the same participants have been used in all conditions (repeated measures or within-subjects).

- Mixed design: several IVs (factors/predictors) have been measured. One or more factors uses different participants (between-subjects) and one or more factors uses the same participants (within-subjects). Thus, there is a cobination of independent (between) and related (within or repated) designs.

“Naming” the ANOVA model follows a number/levels convention. The example in this lesson is a 3X2 ANOVA. We know there are two factors that have three and two levels, respectively:

- rater ethnicity has three levels representing the two ethnic groups that were in prior conflict (Marudese, Dayaknese) and a third group who was uninvolved in the conflict (Javanese);

- photo stimulus has two levels representing members of the two ethnic groups that were in prior conflict (Madurese, Dayaknese);

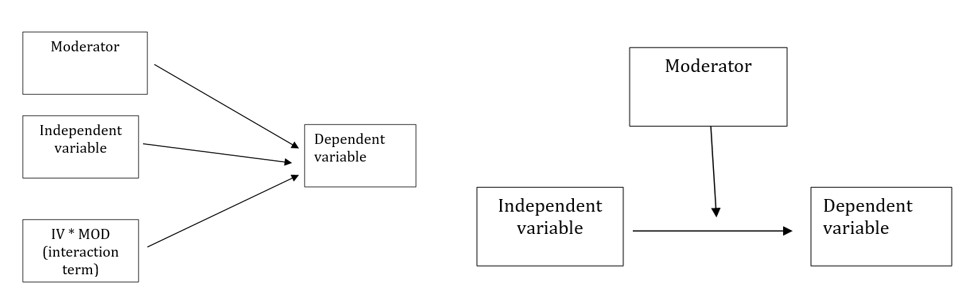

Moderator is what creates an interaction. Below are traditional representations of the statistical and conceptual figures of interaction effects. We will say that Factor B, moderates the relationship between Factor A (the IV) and the DV.

In a later lesson we work an ANCOVA – where we will distinguish between a moderator and a covariate. In lessons on regression models, you will likely be introduced to the notion of mediator.

8.2.1 Workflow for Two-Way ANOVA

The following is a proposed workflow for conducting a two-way ANOVA.

Steps of the workflow include:

- Enter data

- predictors should formatted as as factors (ordered or unordered); the dependent variable should be continuously scaled

- understanding the format of data can often provide clues as to which ANOVA/statistic to use

- Explore data

- graph the data

- compute descriptive statistics

- evaluate distributional assumptions

- assess the homogeneity of variance assumption with Levene’s test

- assess the nomality assumption with the Shapiro Wilk test

- determine if their are outliers; if appropriate, delete

- Compute the omnibus ANOVA

- depending on what you found in the data exploration phase, you may need to run a robust version of the test

- Follow-up testing based on significant main or interaction effects

- significant interactions require test of simple main effects which could be further explored with contrasts, posthoc comparisons, and/or polynomials

- the exact methods you choose will depend upon the tests of assumptions during data exploration

- Managing Type I error

8.3 Research Vignette

The research vignette for this example was located in Kalimantan, Indonesia and focused on bias in young people from three ethnic groups. The Madurese and Dayaknese groups were engaged in ethnic conflict that spanned 1996 to 2001. The last incidence of mass violence was in 2001 where approximately 500 people (mostly from the Madurese ethnic group) were expelled from the province. Ramdhani et al.’s (2018) research hypotheses were based on the roles of the three ethnic groups in the study. According to the author, the Madurese were viewed as the transgressors when they occupied lands and took employment and business opportunities from the Dayaknese. Ramdhani et al. also included a third group who were not involved in the conflict (Javanese). The research participants were students studying in Yogyakara who were not involved in the conflict. They included 39 Madurese, 35 Dyaknese, and 37 Javanese; 83 were male and 28 were female.

In the study (Ramdhani et al., 2018), participants viewed facial pictures of three men and three women (in traditional dress) from each ethnic group (6 photos per ethnic group). Participant were asked, “How do you feel when you see this photo? Please indicate your answers based on your actual feelings.” Participants responded on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicated ratings of higher intensity on that scale. The two scales included the following words:

- Positive: friendly, kind, helpful, happy

- Negative: disgusting, suspicious, hateful, angry

8.3.1 Data Simulation

Below is script to simulate data for the negative reactions variable from the information available from the manuscript (Ramdhani et al., 2018).

library(tidyverse)

set.seed(210731)

#sample size, M and SD for each cell; this will put it in a long file

Negative<-round(c(rnorm(17,mean=1.91,sd=0.73),rnorm(18,mean=3.16,sd=0.19),rnorm(19, mean=3.3, sd=1.05), rnorm(20, mean=3.00, sd=1.07), rnorm(18, mean=2.64, sd=0.95), rnorm(19, mean=2.99, sd=0.80)),3)

#sample size, M and SD for each cell; this will put it in a long file

Positive<-round(c(rnorm(17,mean=4.99,sd=1.38),rnorm(18,mean=3.83,sd=1.13),rnorm(19, mean=4.2, sd=0.82), rnorm(20, mean=4.19, sd=0.91), rnorm(18, mean=4.17, sd=0.60), rnorm(19, mean=3.26, sd=0.94)),3)

ID <- factor(seq(1,111))

Rater <- c(rep("Dayaknese",35), rep("Madurese", 39), rep ("Javanese", 37))

Photo <- c(rep("Dayaknese", 17), rep("Madurese", 18), rep("Dayaknese", 19), rep("Madurese", 20), rep("Dayaknese", 18), rep("Madurese", 19))

#groups the 3 variables into a single df: ID#, DV, condition

Ramdhani_df<- data.frame(ID, Negative, Positive, Rater, Photo) For two-way ANOVA our variables need to be properly formatted. In our case:

- Negative is a continuously scaled DV and should be num

- Positive is a continuously scaled DV and should be num

- Rater should be an unordered factor

- Photo should be an unordered facor

## 'data.frame': 111 obs. of 5 variables:

## $ ID : Factor w/ 111 levels "1","2","3","4",..: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 ...

## $ Negative: num 2.768 1.811 0.869 1.857 2.087 ...

## $ Positive: num 5.91 5.23 3.54 5.63 5.44 ...

## $ Rater : chr "Dayaknese" "Dayaknese" "Dayaknese" "Dayaknese" ...

## $ Photo : chr "Dayaknese" "Dayaknese" "Dayaknese" "Dayaknese" ...Our Negative variable is correctly formatted. Let’s reformat Rater and Photo to be factors and re-evaluate the structure. R’s default is to order the factors alphabetically. In this case this is fine. If we had ordered factors such as dosage (placebo, lo, hi) we would want to respecify the order.

Ramdhani_df[,'Rater'] <- as.factor(Ramdhani_df[,'Rater'])

Ramdhani_df[,'Photo'] <- as.factor(Ramdhani_df[,'Photo'])

str(Ramdhani_df)## 'data.frame': 111 obs. of 5 variables:

## $ ID : Factor w/ 111 levels "1","2","3","4",..: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 ...

## $ Negative: num 2.768 1.811 0.869 1.857 2.087 ...

## $ Positive: num 5.91 5.23 3.54 5.63 5.44 ...

## $ Rater : Factor w/ 3 levels "Dayaknese","Javanese",..: 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ...

## $ Photo : Factor w/ 2 levels "Dayaknese","Madurese": 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ...If you want to export this data as a file to your computer, remove the hashtags to save it (and re-import it) as a .csv (“Excel lite”) or .rds (R object) file. This is not a necessary step.

The code for .csv will likely lose the formatting (i.e., making the Rater and Photo variables factors), but it is easy to view in Excel.

#write the simulated data as a .csv

#write.table(Ramdhani_df, file="RamdhaniCSV.csv", sep=",", col.names=TRUE, row.names=FALSE)

#bring back the simulated dat from a .csv file

#Ramdhani_df <- read.csv ("RamdhaniCSV.csv", header = TRUE)

#str(Ramdhani_df)The code for the .rds file will retain the formatting of the variables, but is not easy to view outside of R.

8.3.2 Quick peek at the data

Let’s first examine the descriptive statistics (e.g., means of the variable, Negative) by group. We can use the describeBy() function from the psych package.

negative.descripts <- psych::describeBy(Negative ~ Rater + Photo, mat = TRUE, data = Ramdhani_df, digits = 3) #digits allows us to round the output

negative.descripts## item group1 group2 vars n mean sd median trimmed mad

## Negative1 1 Dayaknese Dayaknese 1 17 1.818 0.768 1.692 1.783 0.694

## Negative2 2 Javanese Dayaknese 1 18 2.524 0.742 2.391 2.460 0.569

## Negative3 3 Madurese Dayaknese 1 19 3.301 1.030 3.314 3.321 1.294

## Negative4 4 Dayaknese Madurese 1 18 3.129 0.156 3.160 3.136 0.104

## Negative5 5 Javanese Madurese 1 19 3.465 0.637 3.430 3.456 0.767

## Negative6 6 Madurese Madurese 1 20 3.297 1.332 2.958 3.254 1.615

## min max range skew kurtosis se

## Negative1 0.706 3.453 2.747 0.513 -0.881 0.186

## Negative2 1.406 4.664 3.258 1.205 1.475 0.175

## Negative3 1.406 4.854 3.448 -0.126 -1.267 0.236

## Negative4 2.732 3.423 0.691 -0.623 0.481 0.037

## Negative5 2.456 4.631 2.175 -0.010 -1.307 0.146

## Negative6 1.211 5.641 4.430 0.215 -1.238 0.298The write.table() function can be a helpful way to export output to .csv files so that you can manipulate it into tables.

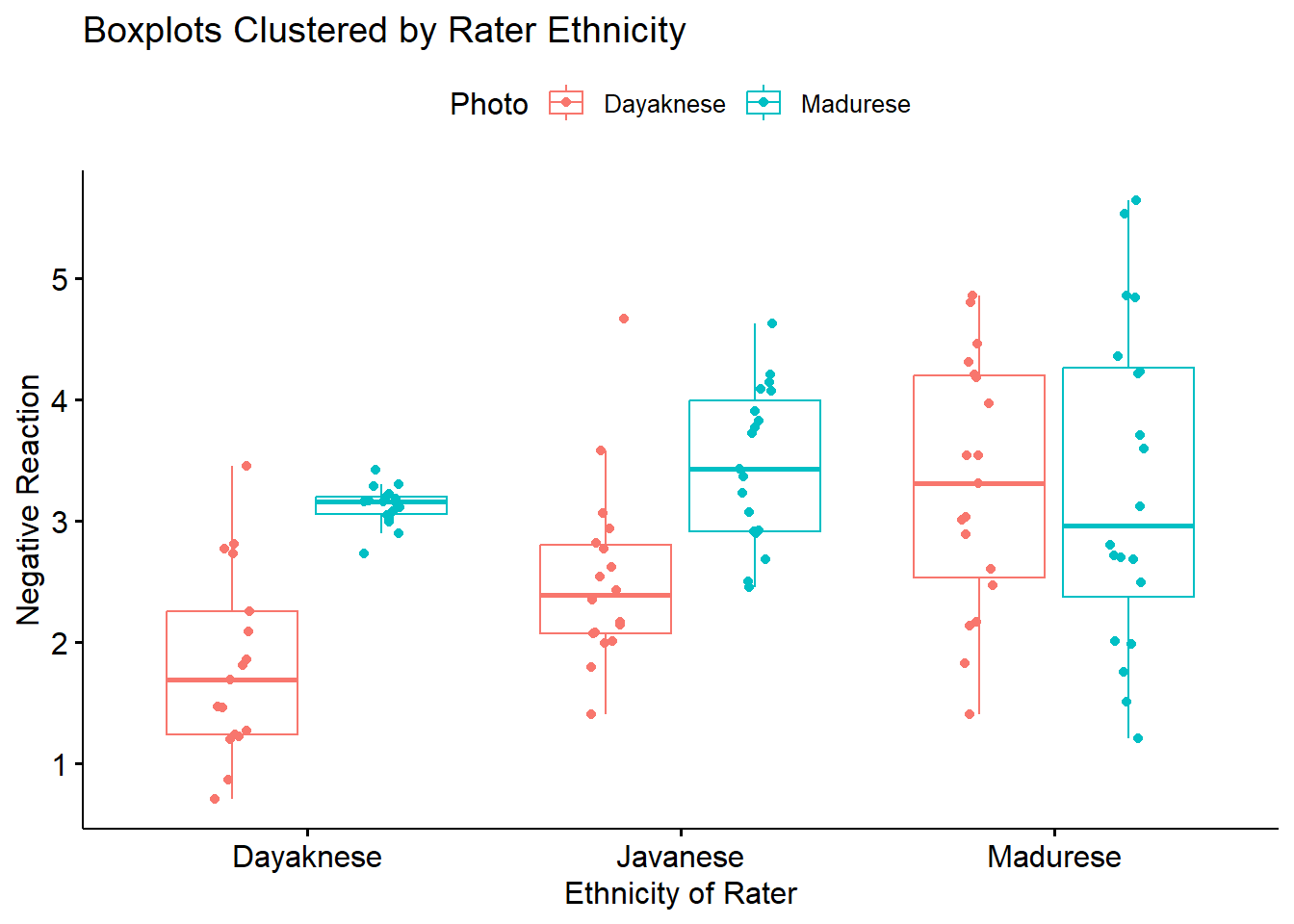

write.table(negative.descripts, file="NegativeDescripts.csv", sep=",", col.names=TRUE, row.names=FALSE)At this stage, it would be useful to plot our data. Figures can assist in the conceptualization of the analysis.

ggpubr::ggboxplot(Ramdhani_df, x = "Rater", y = "Negative", color = "Photo",xlab = "Ethnicity of Rater", ylab = "Negative Reaction", add = "jitter", title = "Boxplots Clustered by Rater Ethnicity")

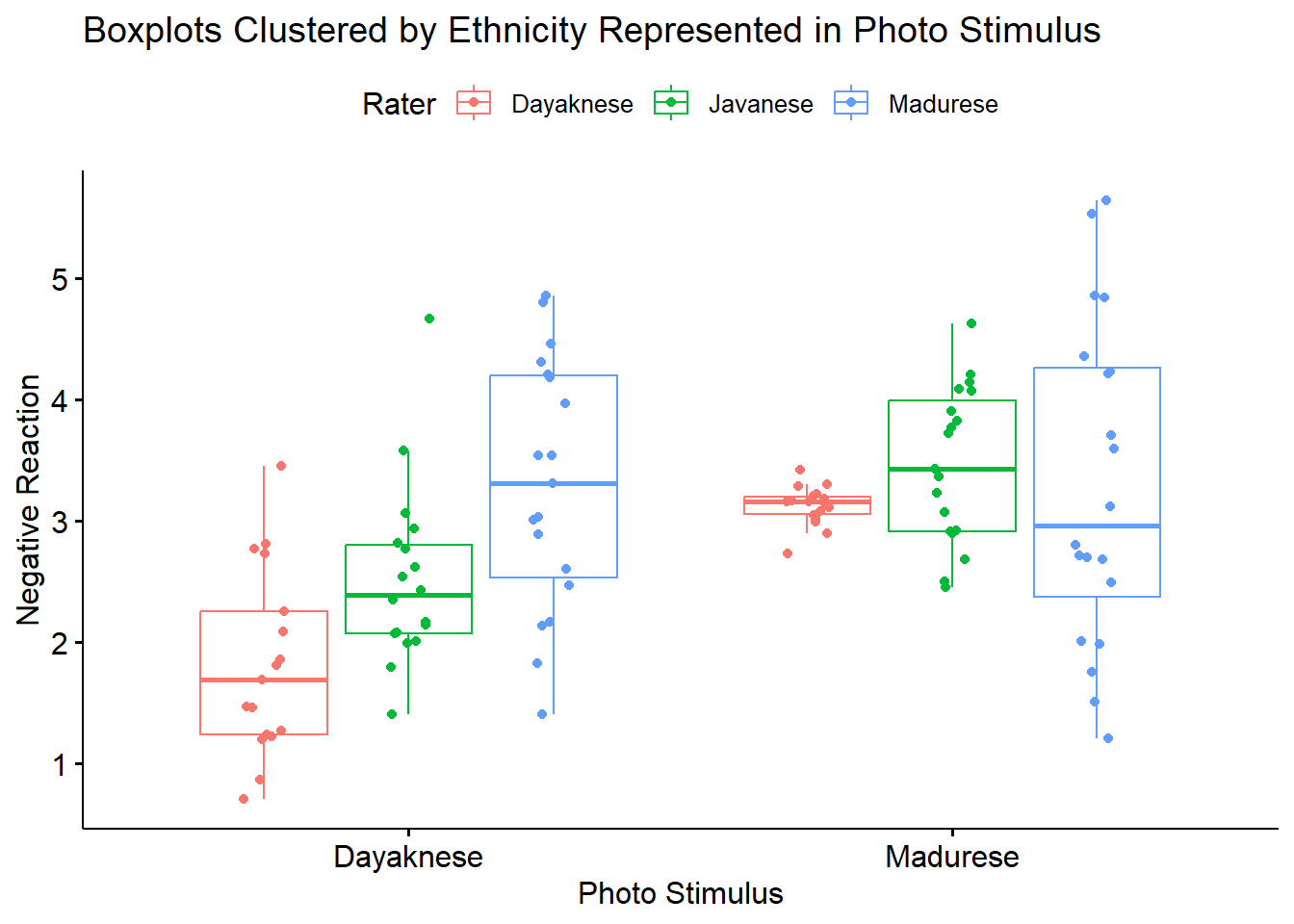

Narrating results is sometimes made easier if variables are switched. There is usually not a right or wrong answer. Here is another view, switching the Rater and Photo predictors.

ggpubr::ggboxplot(Ramdhani_df, x = "Photo", y = "Negative", color = "Rater", xlab = "Photo Stimulus",

ylab = "Negative Reaction", add = "jitter", title = "Boxplots Clustered by Ethnicity Represented in Photo Stimulus")

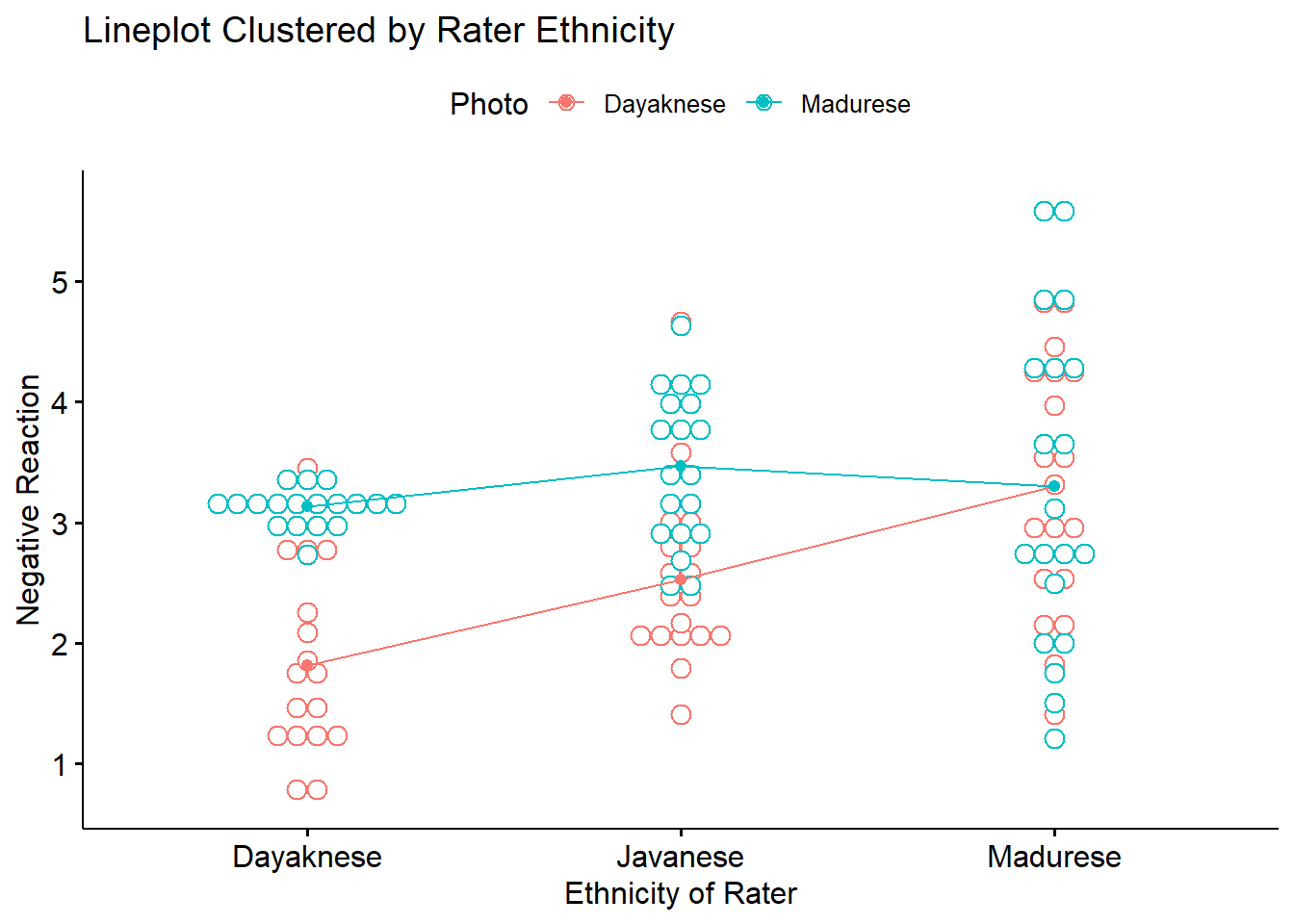

Yet another option plots the raw data as bubbles, the means as lines, and denotes differences in the moderator with color.

ggpubr::ggline(Ramdhani_df, x = "Rater", y = "Negative", color = "Photo", xlab = "Ethnicity of Rater",

ylab = "Negative Reaction", add = c("mean_se", "dotplot"), title = "Lineplot Clustered by Rater Ethnicity")

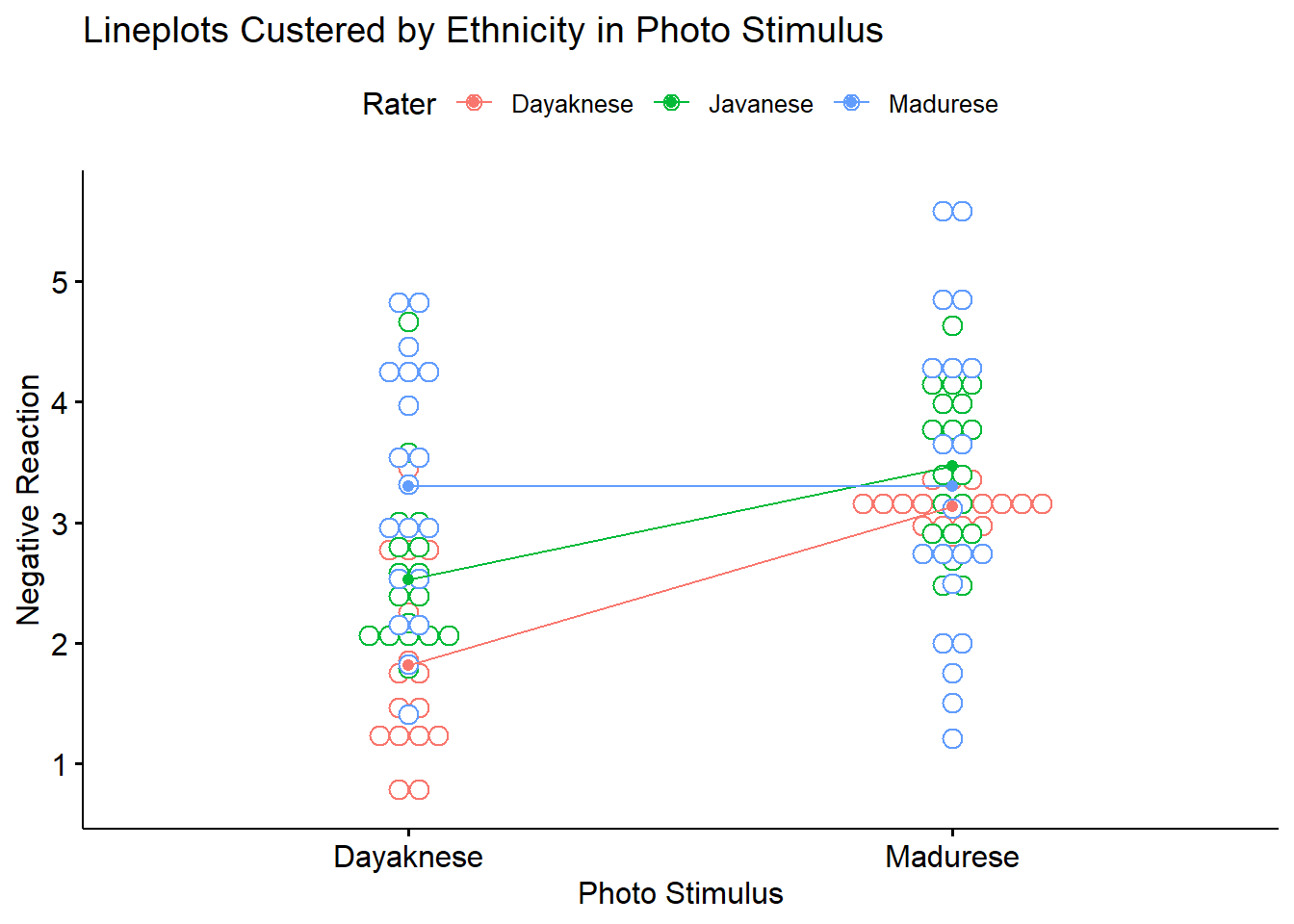

We can reverse this to see if it assists with our conceptualization.

ggpubr::ggline(Ramdhani_df, x = "Photo", y = "Negative", color = "Rater", xlab = "Photo Stimulus",

ylab = "Negative Reaction", add = c("mean_se", "dotplot"), title = "Lineplots Custered by Ethnicity in Photo Stimulus")## Bin width defaults to 1/30 of the range of the data. Pick better value with

## `binwidth`.## Warning: Computation failed in `stat_summary()`.

## Caused by error in `get()`:

## ! object 'mean_se_' of mode 'function' was not found

8.4 Working the Factorial ANOVA (by hand)

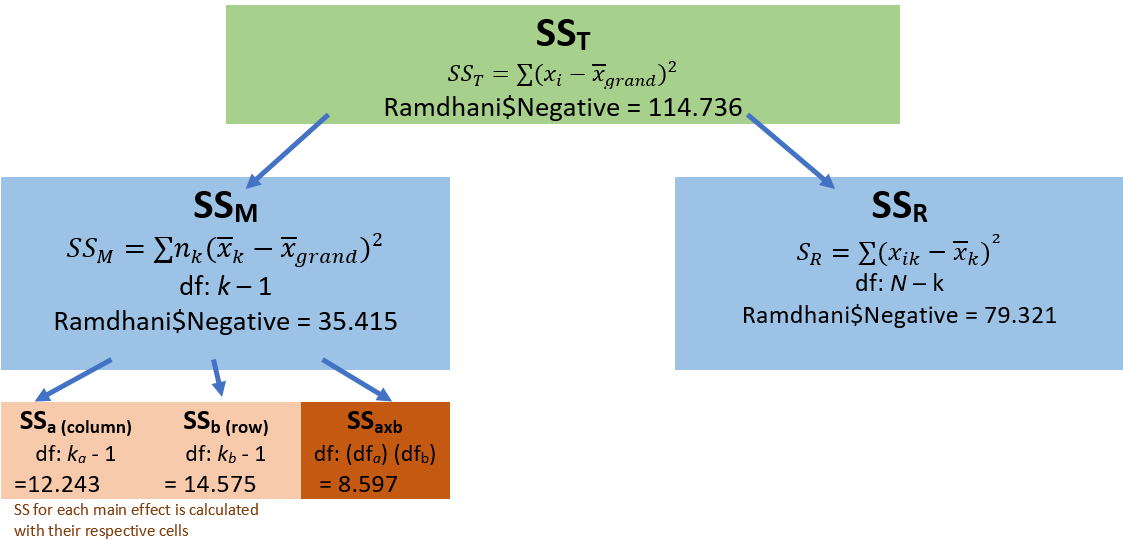

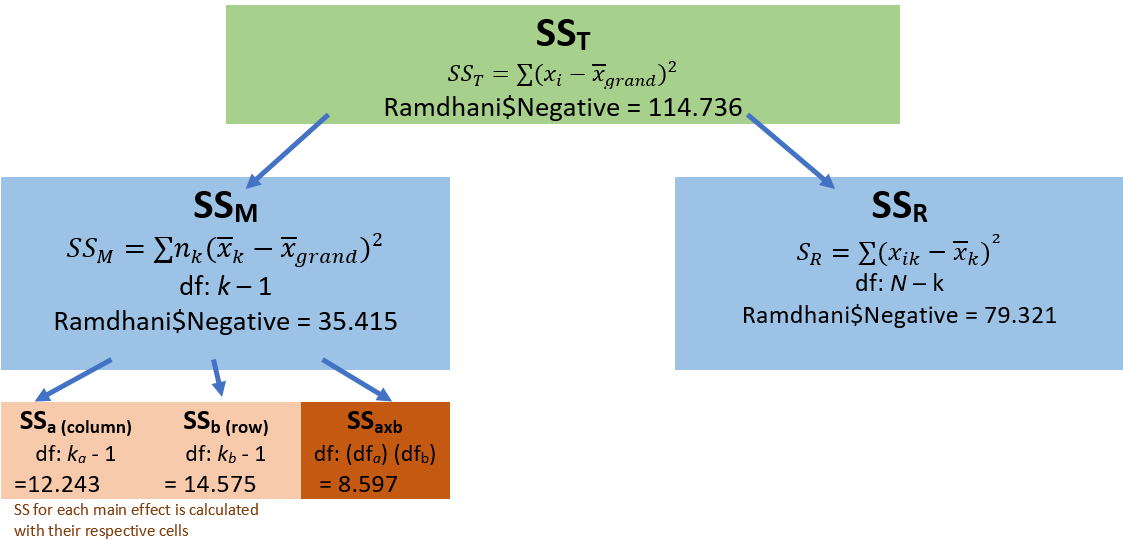

Before we work an ANOVA let’s take a moment to consider what we are doing and how it informs our decision-making. This figure (which already contains “the answers”) may help conceptualize how variance is partitioned.

As in one-way ANOVA, we partition variance into total, model, and residual. However, we now further divide the \(SS_M\) into its respective factors A(column), B(row,) and their a x b product.

In this, we begin to talk about main effects and interactions.

8.4.1 Sums of Squares Total

Our formula is the same as it was for one-way ANOVA:

\[SS_{T}= \sum (x_{i}-\bar{x}_{grand})^{2}\] Let’s calculate it for the Ramdhani et al. (2018) data. Our grand (i.e., overall) mean is

## [1] 2.947369Subtracting the grand mean from each Negative rating yields a mean difference.

library(tidyverse)

Ramdhani_df <- Ramdhani_df %>%

mutate(m_dev = Negative-mean(Negative))

head(Ramdhani_df)## ID Negative Positive Rater Photo m_dev

## 1 1 2.768 5.907 Dayaknese Dayaknese -0.1793694

## 2 2 1.811 5.234 Dayaknese Dayaknese -1.1363694

## 3 3 0.869 3.544 Dayaknese Dayaknese -2.0783694

## 4 4 1.857 5.628 Dayaknese Dayaknese -1.0903694

## 5 5 2.087 5.438 Dayaknese Dayaknese -0.8603694

## 6 6 0.706 5.833 Dayaknese Dayaknese -2.2413694Pop quiz: What’s the sum of our new m_dev variable?

Let’s find out!

## [1] -0.000000000000007549517Of course! The sum of squared deviations around the mean is zero. Next we square those mean deviations.

## ID Negative Positive Rater Photo m_dev m_devSQ

## 1 1 2.768 5.907 Dayaknese Dayaknese -0.1793694 0.03217337

## 2 2 1.811 5.234 Dayaknese Dayaknese -1.1363694 1.29133534

## 3 3 0.869 3.544 Dayaknese Dayaknese -2.0783694 4.31961924

## 4 4 1.857 5.628 Dayaknese Dayaknese -1.0903694 1.18890536

## 5 5 2.087 5.438 Dayaknese Dayaknese -0.8603694 0.74023545

## 6 6 0.706 5.833 Dayaknese Dayaknese -2.2413694 5.02373665Then we sum the squared mean deviations.

## [1] 114.7746This value, 114.775, the sum of squared deviations around the grand mean, is our \(SS_T\); the associated degrees of freedom is \(N\) - 1.

In factorial ANOVA, we divide \(SS_T\) into model/between sums of squares and residual/within sums of squares.

8.4.2 Sums of Squares for the Model

\[SS_{M}= \sum n_{k}(\bar{x}_{k}-\bar{x}_{grand})^{2}\]

The model generally represents the notion that the means are different than each other. We want the variation between our means to be greater than the variation within each of the groups from which our means are calculated.

In factorial ANOVA, we need means for each of the combinations of the factors. We have a 3 x 2 model:

- Rater with three levels: Dayaknese, Madurese, Javanese

- Photo with two levels: Dayaknese, Madurese

Let’s repeat some code we used before to obtain the cell-level means and cell sizes.

## item group1 group2 vars n mean sd median trimmed mad

## Negative1 1 Dayaknese Dayaknese 1 17 1.818 0.768 1.692 1.783 0.694

## Negative2 2 Javanese Dayaknese 1 18 2.524 0.742 2.391 2.460 0.569

## Negative3 3 Madurese Dayaknese 1 19 3.301 1.030 3.314 3.321 1.294

## Negative4 4 Dayaknese Madurese 1 18 3.129 0.156 3.160 3.136 0.104

## Negative5 5 Javanese Madurese 1 19 3.465 0.637 3.430 3.456 0.767

## Negative6 6 Madurese Madurese 1 20 3.297 1.332 2.958 3.254 1.615

## min max range skew kurtosis se

## Negative1 0.706 3.453 2.747 0.513 -0.881 0.186

## Negative2 1.406 4.664 3.258 1.205 1.475 0.175

## Negative3 1.406 4.854 3.448 -0.126 -1.267 0.236

## Negative4 2.732 3.423 0.691 -0.623 0.481 0.037

## Negative5 2.456 4.631 2.175 -0.010 -1.307 0.146

## Negative6 1.211 5.641 4.430 0.215 -1.238 0.298#Note. Recently my students and I have been having intermittent struggles with the describeBy function in the psych package. We have noticed that it is problematic when using .rds files and when using data directly imported from Qualtrics. If you are having similar difficulties, try uploading the .csv file and making the appropriate formatting changes.We also need the grand mean (i.e., the mean that disregards [or “collapses across”] the factors).

## [1] 2.947369This formula occurs in six chunks, representing the six cells of our designed. In each of the chunks we have the \(n\), group mean, and grand mean.

17*(1.818 - 2.947)^2 + 18*(2.524 - 2.947)^2 + 19*(3.301 - 2.947)^2 + 18*(3.129 - 2.947)^2 + 19*(3.465 - 2.947)^2 + 20*(3.297 - 2.947)^2## [1] 35.41501This value, 35.415, \(SS_M\) is the value accounted for by the model. That is, the amount of variance accounted for by the grouping variable/factors, Rater and Photo.

8.4.3 Sums of Squares Residual (or within)

\(SS_R\) is error associated with within group variability. If people are randomly assigned to conditions there should be no other confounding variable. Thus, all \(SS_R\) variability is uninteresting for the research and treated as noise.

\[SS_{R}= \sum(x_{ik}-\bar{x}_{k})^{^{2}}\] Here’s another configuration of the same:

\[SS_{R}= s_{group1}^{2}(n-1) + s_{group2}^{2}(n-1) + s_{group3}^{2}(n-1) + s_{group4}^{2}(n-1) + s_{group5}^{2}(n-1) + s_{group6}^{2}(n-1))\]

Again, the formula is in six chunks – but this time the calculations are within-group. We need the variance (the standard deviation squared) for the calculation. We can retrieve these from the descriptive statistics.

## item group1 group2 vars n mean sd median trimmed mad

## Negative1 1 Dayaknese Dayaknese 1 17 1.818 0.768 1.692 1.783 0.694

## Negative2 2 Javanese Dayaknese 1 18 2.524 0.742 2.391 2.460 0.569

## Negative3 3 Madurese Dayaknese 1 19 3.301 1.030 3.314 3.321 1.294

## Negative4 4 Dayaknese Madurese 1 18 3.129 0.156 3.160 3.136 0.104

## Negative5 5 Javanese Madurese 1 19 3.465 0.637 3.430 3.456 0.767

## Negative6 6 Madurese Madurese 1 20 3.297 1.332 2.958 3.254 1.615

## min max range skew kurtosis se

## Negative1 0.706 3.453 2.747 0.513 -0.881 0.186

## Negative2 1.406 4.664 3.258 1.205 1.475 0.175

## Negative3 1.406 4.854 3.448 -0.126 -1.267 0.236

## Negative4 2.732 3.423 0.691 -0.623 0.481 0.037

## Negative5 2.456 4.631 2.175 -0.010 -1.307 0.146

## Negative6 1.211 5.641 4.430 0.215 -1.238 0.298Calculating \(SS_R\)

((.768^2)*(17-1))+ ((.742^2)*(18-1)) + ((1.030^2)*(19-1)) + ((.156^2)*(18-1)) + ((.637^2)*(19-1)) + ((1.332^2)*(20-1))## [1] 79.32078The value for our \(SS_R\) is 79.321. Its degrees of freedom is \(N - k\). That is, the total \(N\) minus the number of groups:

## [1] 1058.4.4 A Recap on the Relationship between \(SS_T\), \(SS_M\), and \(SS_R\)

\(SS_T = SS_M + SS_R\) In our case:

- \(SS_T\) was 114.775

- \(SS_M\) was 35.415

- \(SS_R\) was 79.321

Considering rounding error, we were successful!

## [1] 114.7368.4.5 Calculating SS for Each Factor and Their Products

8.4.5.1 Rater Main Effect

\(SS_a:Rater\) is calculated the same way as \(SS_M\) for one-way ANOVA. Simply collapse across Photo and calculate the marginal means for Negative as a function of the Rater’s ethnicity.

Reminder of the formula: \(SS_{a:Rater}= \sum n_{k}(\bar{x}_{k}-\bar{x}_{grand})^{2}\)

There are three cells involved in the calculation of \(SS_a:Rater\).

## item group1 vars n mean sd median trimmed mad min max

## Negative1 1 Dayaknese 1 35 2.492 0.856 2.900 2.561 0.480 0.706 3.453

## Negative2 2 Javanese 1 37 3.007 0.831 2.913 2.986 0.984 1.406 4.664

## Negative3 3 Madurese 1 39 3.299 1.179 3.116 3.288 1.588 1.211 5.641

## range skew kurtosis se

## Negative1 2.747 -0.682 -1.132 0.145

## Negative2 3.258 0.239 -0.923 0.137

## Negative3 4.430 0.117 -1.036 0.189Again, we need the grand mean.

## [1] 2.947369Now to calculate the Rater main effect.

## [1] 12.243228.4.5.2 Photo Main Effect

\(SS_b:Photo\) is calculated the same way as \(SS_M\) for one-way ANOVA. Simply collapse across Rater and calculate the marginal means for Negative as a function of the ethnicity reflected in the Photo stimulus:

Reminder of the formula: \(SS_{a:Photo}= \sum n_{k}(\bar{x}_{k}-\bar{x}_{grand})^{2}\).

With Photo, we have only two cells.

## item group1 vars n mean sd median trimmed mad min max

## Negative1 1 Dayaknese 1 54 2.575 1.043 2.449 2.516 0.921 0.706 4.854

## Negative2 2 Madurese 1 57 3.300 0.871 3.166 3.280 0.667 1.211 5.641

## range skew kurtosis se

## Negative1 4.148 0.47 -0.555 0.142

## Negative2 4.430 0.35 0.581 0.115Again, we need the grand mean.

## [1] 2.947369## [1] 14.575458.4.5.3 Interaction effect

The interaction term is simply the \(SS_M\) remaining after subtracting the SS from the main effects.

\(SS_{axb} = SS_M - (SS_a + SS_b)\)

## [1] 8.597Let’s revisit the figure I showed at the beginning of this section to see, again, how variance is partitioned.

8.4.6 Source Table Games!

As in the lesson for one-way ANOVA, we can use the information in this source table to determine if we have statistically significance in the model. There is enough information in the source table to be able to calculate all the elements. The formulas in the table provide some hints. Before scrolling onto the answers, try to complete it yourself.

| Summary ANOVA for Negative Reaction |

|---|

| Source | SS | df | \(MS = \frac{SS}{df}\) | \(F = \frac{MS_{source}}{MS_{resid}}\) | \(F_{CV}\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | \(k-1\) | ||||

| a | \(k_{a}-1\) | ||||

| b | \(k_{b}-1\) | ||||

| aXb | \((df_{a})(df_{b})\) | ||||

| Residual | \(n-k\) | ||||

| Total |

## [1] 7.083## [1] 6.1215## [1] 14.575## [1] 4.2985## [1] 0.7554381## [1] 9.381457## [1] 8.108609## [1] 19.30464## [1] 5.69404To find the \(F_{CV}\) we can use an F distribution table.

Or use a look-up function, which follows this general form: qf(p, df1, df2. lower.tail=FALSE)

## [1] 2.300888## [1] 3.082852## [1] 3.931556When the \(F\) value exceeds the \(F_{CV}\), the effect is statistically significant.

| Summary ANOVA for Negative Reaction |

|---|

| Source | SS | df | \(MS = \frac{SS}{df}\) | \(F = \frac{MS_{source}}{MS_{resid}}\) | \(F_{CV}\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 35.415 | 5 | 7.083 | 9.381 | 2.301 |

| a | 12.243 | 2 | 6.122 | 8.109 | 3.083 |

| b | 14.575 | 1 | 14.575 | 19.305 | 3.932 |

| aXb | 8.597 | 2 | 4.299 | 5.694 | 3.083 |

| Residual | 79.321 | 105 | 0.755 | ||

| Total | 114.775 |

8.4.7 Interpreting the results

What have we learned?

- there is a main effect for Rater

- there is a main effect for Photo

- there is a significant interaction effect

In the face of this significant interaction effect, we would follow-up by investigating the interaction effect. Why? The significant interaction effect means that findings (e.g., the story of the results) are more complex than group identity or photo stimulus, alone, can explain.

You may notice that the results from the hand calculation are slightly different from the results I will obtain with the R packages. This is because the formula we have used for the hand-calculations utilizes an approach to calculating the sums of squares that presumes that we have a balanced design (i.e., that the cell sizes are equal). When cell sizes are unequal (i.e., an unbalanced design) the Type II package in rstatix::anova_test will produce different result.

Should we be concerned? No (and yes). My purpose in teaching hand calculations is for creating a conceptual overview of what is occurring in ANOVA models. If this lesson was a deeper exploration into the inner workings of ANOVA, we would take more time to understand what is occurring. My goal is to provide you with enough of an introduction to ANOVA that you would be able to explore further which sums of squares type would be most appropriate for your unique ANOVA model.

8.5 Working the Factorial ANOVA with R Packages

8.5.1 Evaluating the statistical assumptions

All statistical tests have some assumptions about the data. I have marked our Two-Way ANOVA Workflow with a yellow box outlined in red to let us know that we are just beginning the process of analyzing our data with an evaluation of the statistical assumptions.

The are four critical assumptions in factorial ANOVA:

- Cases represent random samples from the populations

- This is an issue of research design

- Although we see ANOVA used (often incorrectly) in other settings, ANOVA was really designed for the random clinical trial (RCT).

- Scores on the DV are independent of each other.

- This is an issue of research design

- With correlated observations, there is a dramatic increase of Type I error

- There are alternative statistics designed for analyzing data that has dependencies (e.g., repeated measures ANOVA, dyadic data analysis, multilevel modeling)

- The DV is normally distributed for each of the populations

- that is, data for each cell (representing the combinations of each factor) is normally distributed

- Population variances of the DV are the same for all cells

- When cell sizes are not equal, ANOVA not robust to this violation and cannot trust F ratio

Even though we position the evaluation of assumptions first – some of the best tests of the assumptions use the resulting ANOVA model. Because of this, I will quickly run the model now. I will not explain the results until after we evaluate the assumptions.

## Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

## Rater 2 12.21 6.103 8.077 0.000546 ***

## Photo 1 14.62 14.619 19.346 0.0000262 ***

## Rater:Photo 2 8.61 4.304 5.696 0.004480 **

## Residuals 105 79.34 0.756

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1## Tables of means

## Grand mean

##

## 2.947369

##

## Rater

## Dayaknese Javanese Madurese

## 2.492 3.007 3.299

## rep 35.000 37.000 39.000

##

## Photo

## Dayaknese Madurese

## 2.575 3.301

## rep 54.000 57.000

##

## Rater:Photo

## Photo

## Rater Dayaknese Madurese

## Dayaknese 1.818 3.129

## rep 17.000 18.000

## Javanese 2.524 3.465

## rep 18.000 19.000

## Madurese 3.301 3.298

## rep 19.000 20.0008.5.1.1 Is the dependent variable normally distributed?

8.5.1.1.1 Is there evidence of skew or kurtosis?

Let’s start by analyzing skew and kurtosis. Skew and kurtosis are one way to evaluate whether or not data are normally distributed. When we use the “type=1” argument, the skew and kurtosis indices in psych:describe (or psych::describeBy) can be interpreted according to Kline’s (2016a) guidelines. Regarding skew, values greater than the absolute value of 3.0 are generally considered “severely skewed.” Regarding kurtosis, “severely kurtotic” is argued to be anywhere greater the absolute values of 8 to 20. Kline recommended using a conservative threshold of the absolute value of 10.

## item group1 group2 vars n mean sd median trimmed mad

## Negative1 1 Dayaknese Dayaknese 1 17 1.818 0.768 1.692 1.783 0.694

## Negative2 2 Javanese Dayaknese 1 18 2.524 0.742 2.391 2.460 0.569

## Negative3 3 Madurese Dayaknese 1 19 3.301 1.030 3.314 3.321 1.294

## Negative4 4 Dayaknese Madurese 1 18 3.129 0.156 3.160 3.136 0.104

## Negative5 5 Javanese Madurese 1 19 3.465 0.637 3.430 3.456 0.767

## Negative6 6 Madurese Madurese 1 20 3.297 1.332 2.958 3.254 1.615

## min max range skew kurtosis se

## Negative1 0.706 3.453 2.747 0.562 -0.608 0.186

## Negative2 1.406 4.664 3.258 1.313 2.017 0.175

## Negative3 1.406 4.854 3.448 -0.137 -1.069 0.236

## Negative4 2.732 3.423 0.691 -0.679 0.903 0.037

## Negative5 2.456 4.631 2.175 -0.010 -1.114 0.146

## Negative6 1.211 5.641 4.430 0.232 -1.048 0.298Using guidelines from Kline (2016b) our values for skewness fall below |3.0| and our values for kurtosis fall below |10|.

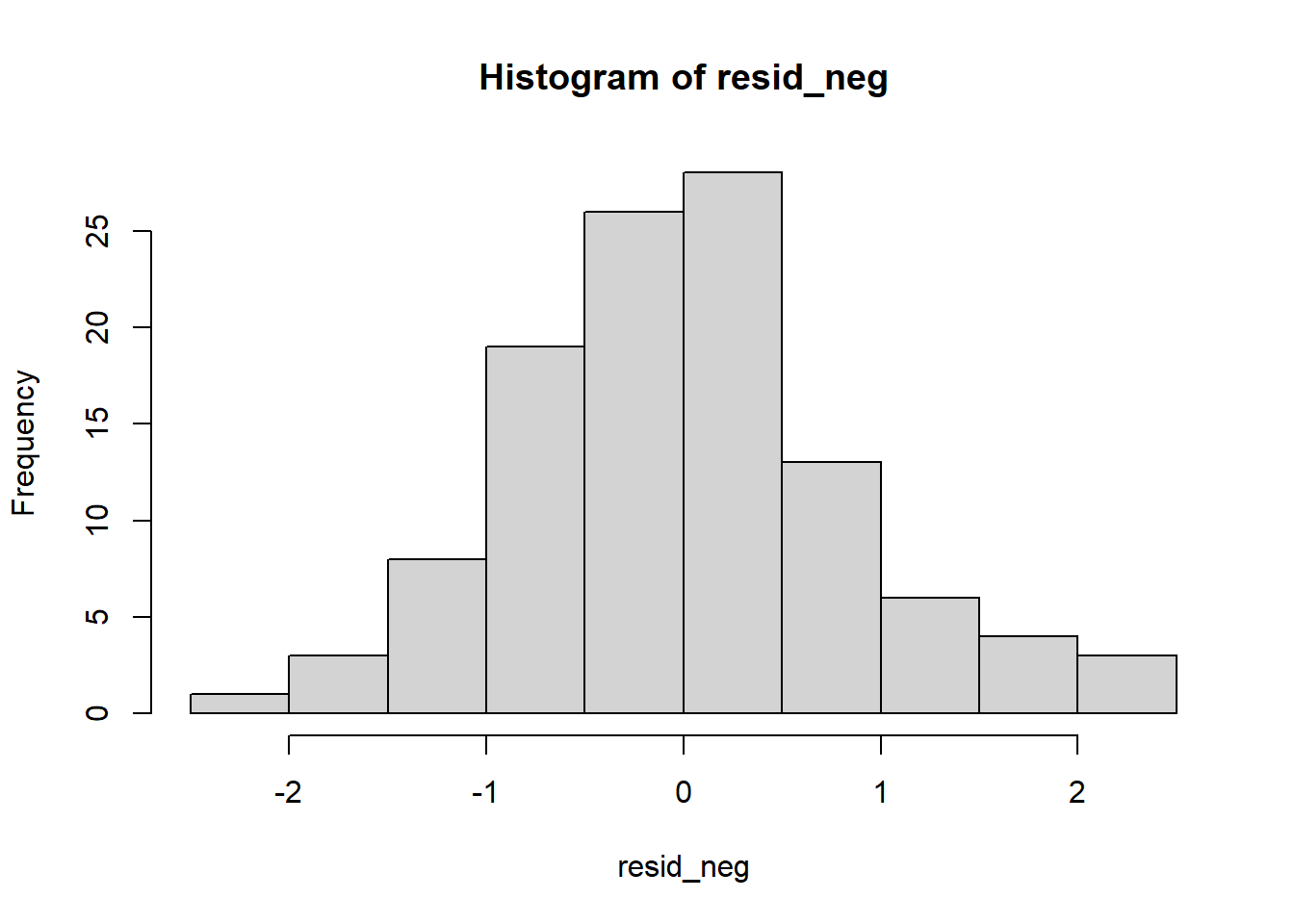

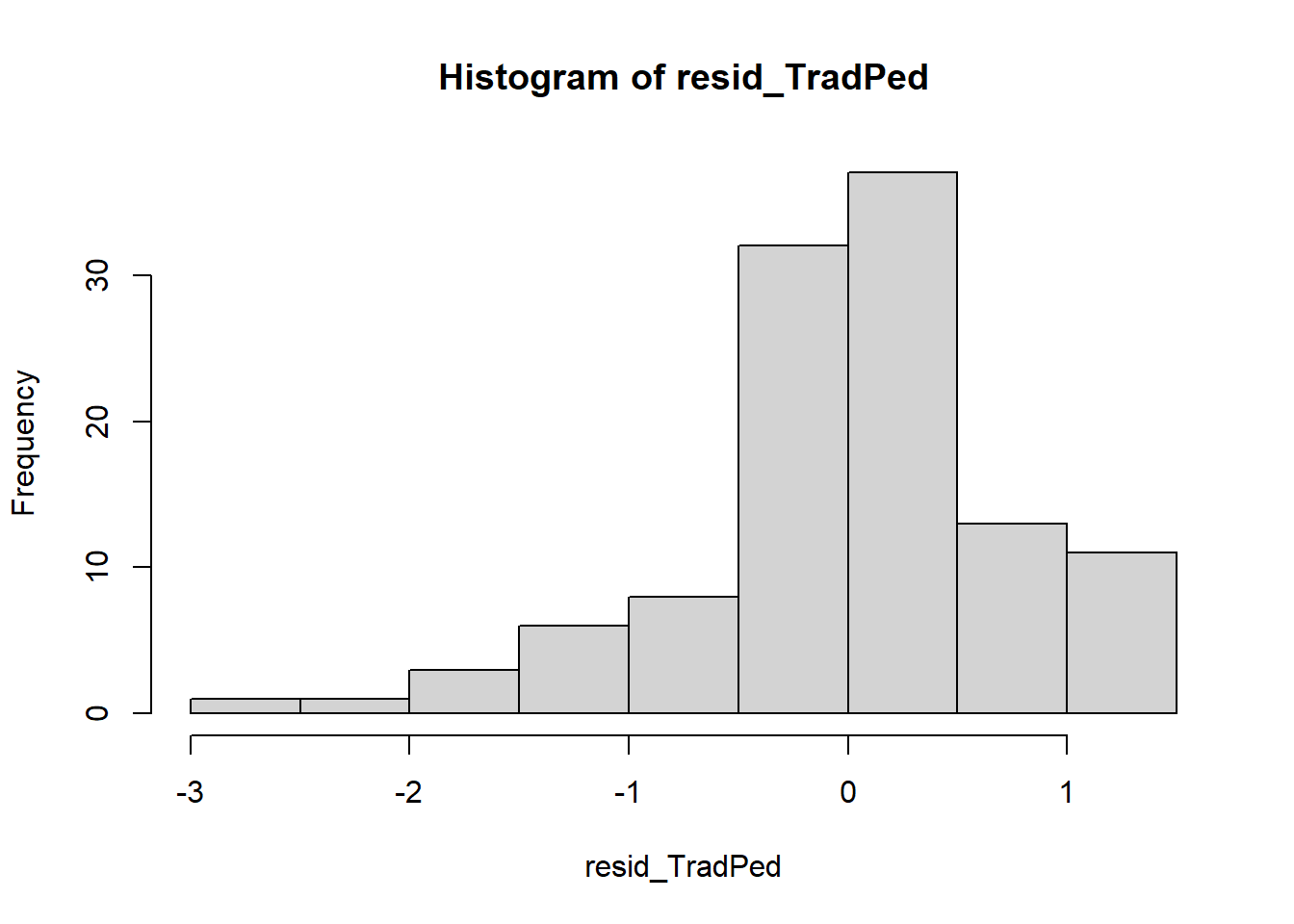

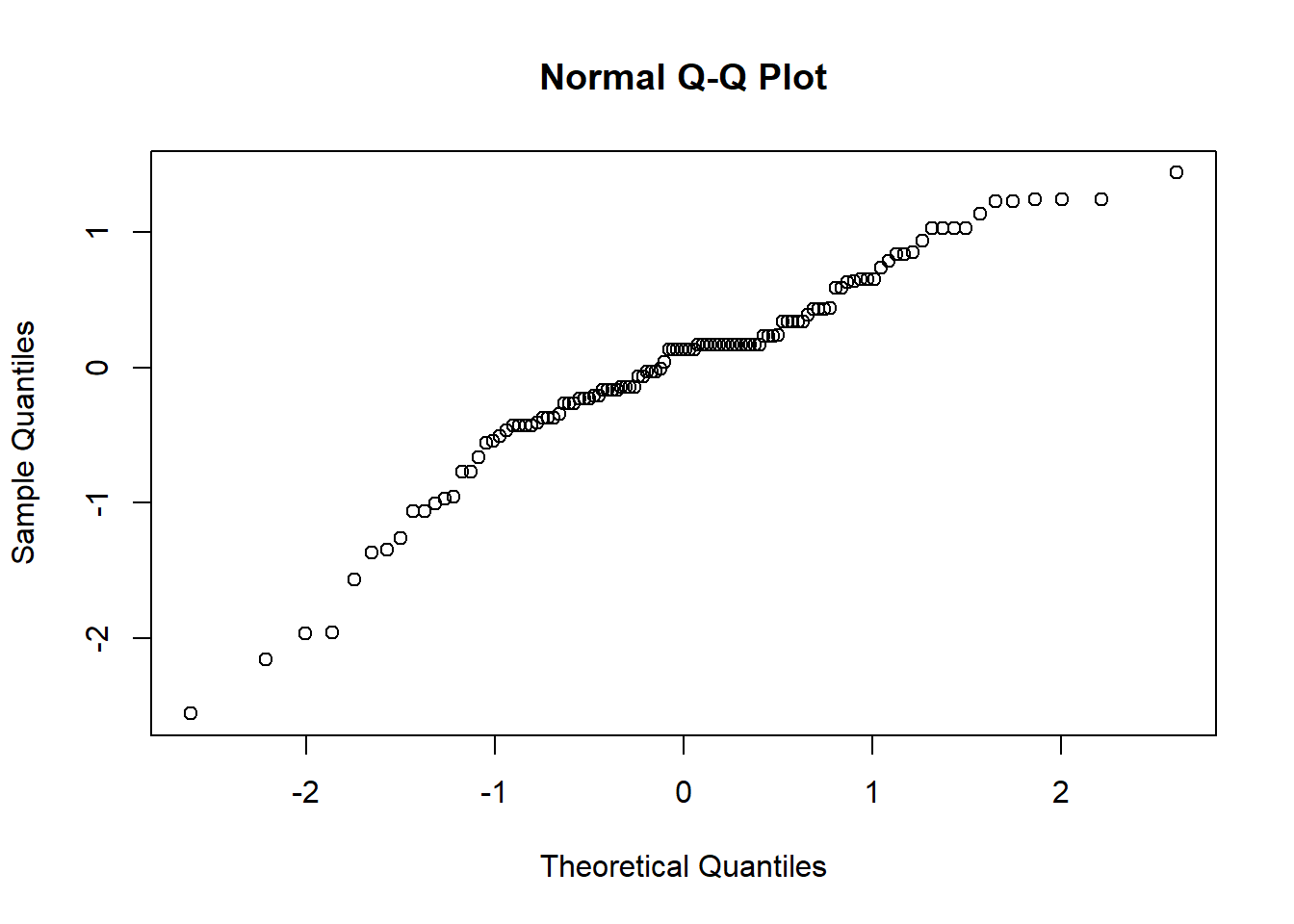

8.5.1.1.2 Are the model residuals normally distributed?

We can further investigate normality with the Shapiro-Wilk test. The assumption requires that the distribution be normal in each of the levels of each factor. In the case of multiple factors (such as is the case in factorial ANOVA), the assumption requires a normal distribution in each combination of these levels (e.g., Javanese rater of Dyaknese photo). In this lesson’s 3 x 2 ANOVA, there are six such combinations. This cell-level analysis has been demonstrated in one-way ANOVA and independent t-test lessons. To the degree that there are many factorial combinations (and therefore, cells), this approach becomes unwieldy to calculate, interpret, and report. The cell-level analysis of normality is also only appropriate when there are a low number of levels/groupings and there are many data points per group. Thus, as models become more complex, researchers turn to the model-based option for assessing normality. To do this, we first create an object that tests our research model.

Just a paragraph or two earlier, I ran the factorial ANOVA and saved the results in an object. Among the information contained in that object are residuals. Residuals are the unexplained variance in the outcome (or dependent) variable after accounting for the predictor (or independent) variable. In the code below we extract the residuals (i.e., that which is left-over/unexplained) from the model. We can examine their distribution with a plot.

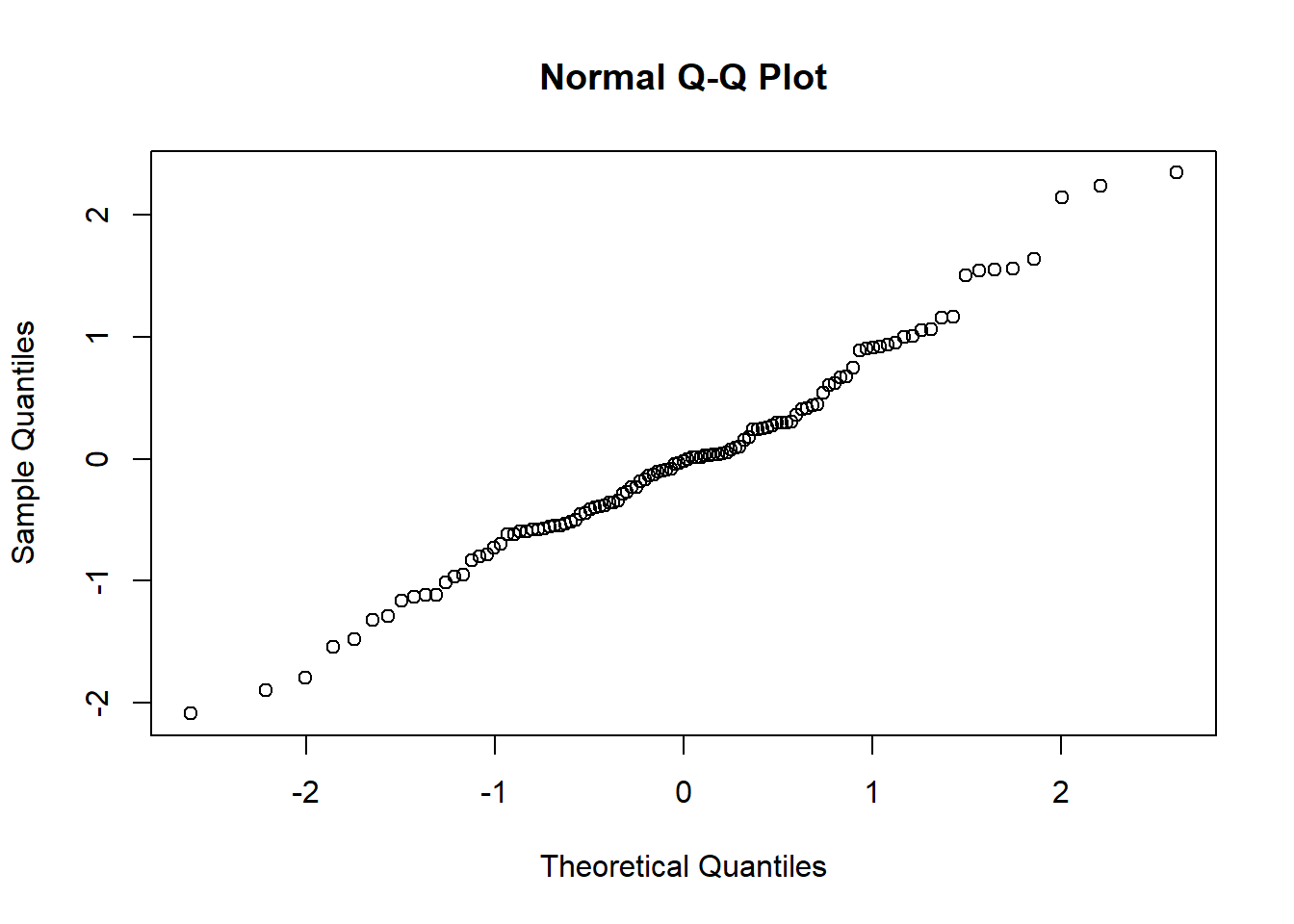

Next, we can take a “look” them with a couple of plots.

So far so good – our distribution of residuals (i.e., what is leftover after the model is applied) resembles a normal distribution.

The Q-Q plot provides another view. The dots represent the residuals. When they are relatively close to the line they not only suggest good fit of the model, but we know they are small and evenly distributed around zero (i.e., normally distributed).

Additionally, we can formally test the distribution of the residuals with a Shapiro test. We want the associated p value to be greater than 0.05.

##

## Shapiro-Wilk normality test

##

## data: resid_neg

## W = 0.98464, p-value = 0.2344Whooo hoo! \(p > 0.05\). This means that our distribution of residuals is not statistically significantly different from a normal distribution (\(W = 0.985, p = 0.234\)).

8.5.1.1.3 Are there outliers?

If our data pointed to significant violations of normality, we could consider identifying and removing outliers. Removing data is a serious consideration that should not be made lightly. If needed, though, here is a tool to inspect the data and then, if necessary, remove it.

We can think of outlier identification in a couple of ways. First, we might look at dependent variable across the entire dataset. That is, without regard to the levels of the grouping variable. We can point rstatix::identify_outliers() to the data.

## ID Negative Positive Rater Photo m_dev m_devSQ is.outlier

## 1 73 5.641 4.813 Madurese Madurese 2.693631 7.255646 TRUE

## is.extreme

## 1 FALSEOur results indicate that one case (ID = 73) had an outlier (TRUE), but it was not extreme (FALSE).

Let’s re-run the code, this time requiring it to look within each of the grouping levels of the condition variable.

## # A tibble: 3 × 9

## Rater Photo ID Negative Positive m_dev m_devSQ is.outlier is.extreme

## <fct> <fct> <fct> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <lgl> <lgl>

## 1 Dayaknese Madure… 18 2.73 5.22 -0.215 0.0464 TRUE FALSE

## 2 Dayaknese Madure… 19 3.42 3.17 0.476 0.226 TRUE FALSE

## 3 Javanese Dayakn… 87 4.66 3.54 1.72 2.95 TRUE FALSEThis time there are three cases where there are outliers (TRUE), but they are not extreme (FALSE). Handily, the function returns information about each row of data. We can use such information to help us delete it.

Let’s say that, after very careful consideration, we decided to remove the case with ID = 18. We could use dplyr::filter() to do so. In this code, the filter() function locates all the cases where ID = 18. The exclamation point that precedes the equal sign indicates that the purpose is to remove the case.

Once executed, we can see that this case is no longer in the dataframe. Although I demonstrated this in the accompanying lecture, I have hashtagged out the command because I would not delete the case. If you already deleted the case, you can return the hashtag and re-run all the code up to this point.

Here’s how I would summarize our data in terms of normality:

Factorial ANOVA assumes that the dependent variable is normally is distributed for all cells in the design. Skew and kurtosis values for each factorial combinations fell below the guidelines recommended by Kline (2016a). That is, they were below the absolute values of 3 for skew and 10 for kurtosis. Similarly, no extreme outliers were identified and results of the Shapiro-Wilk normality test (applied to the residuals from the factorial ANOVA model) suggested that model residuals did not differ significantly from a normal distribution (\(W = 0.9846, p = 0.234\)).

8.5.1.2 Are the variances of the dependent variable similar across the levels of the grouping factors?

We can evaluate the homogeneity of variance test with the Levene’s test for the equality of error variances. Levene’s requires a fully saturated model. This means that the prediction model requires an interaction effect (not just two, non-interacting predictors). We can use the rstatix::levene_test(). Within the function we point to the dataset, then specify the formula of the factorial ANOVA. That is, predicting Negative from the Rater and Photo factors. The asterisk indicates that they will also be added as an interaction term.

## # A tibble: 1 × 4

## df1 df2 statistic p

## <int> <int> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 5 105 8.63 0.000000700Levene’s test, itself, is an F-test. Thus, its reporting assumes the form of an F-string. Our result has indicated a violation of the homogeneity of variance assumption (\(F[5, 105] = 8.634, p < .001)\). This is not surprising as the boxplots displayed some widely varying variances.

Should we be concerned? Addressing violations of homogeneity of variance in factorial ANOVA is complex. The following have been suggested:

- One approach is to use different error variances in follow-up to the omnibus. Kassambara (n.d.-a) suggested that separate one-way ANOVAs for the analysis of simple main effects will provide these separate error terms.

- Green and Salkind (2017c) indicated that we should become more concerned about the trustworthiness of the p values from the omnibus two-way ANOVA when this assumption is violated and the cell sizes are unequal. In today’s research vignette, our design is balanced (i.e., the cell sizes are quite similar).

8.5.1.3 Summarizing results from the analysis of assumptions

It is common for an APA style results section to begin with a review of the evaluation of the statistical assumptions. As we have just finished these analyses, I will document what we have learned so far:

Factorial ANOVA assumes that the dependent variable is normally is distributed for all cells in the design. Skew and kurtosis values for each factorial combinations fell below the guidelines recommended by Kline (2016a). That is, they were below the absolute values of 3 for skew and 10 for kurtosis. Similarly, no extreme outliers were identified and results of the Shapiro-Wilk normality test (applied to the residuals from the factorial ANOVA model) suggested that model residuals did not differ significantly from a normal distribution (\(W = 0.9846, p = 0.234\)). Results of Levene’s test for equality of error variances indicated a violation of the homogeneity of variance assumption, (\(F[5, 105] = 8.834, p < .001\)). Given that cell sample sizes were roughly equal and greater than 15, each (Green & Salkind, 2017c) we proceded with the two-way ANOVA.

8.5.2 Evaluating the Omnibus ANOVA

The F-tests associated with the two-way ANOVA are the omnibus – providing the result for the main and interaction effects.

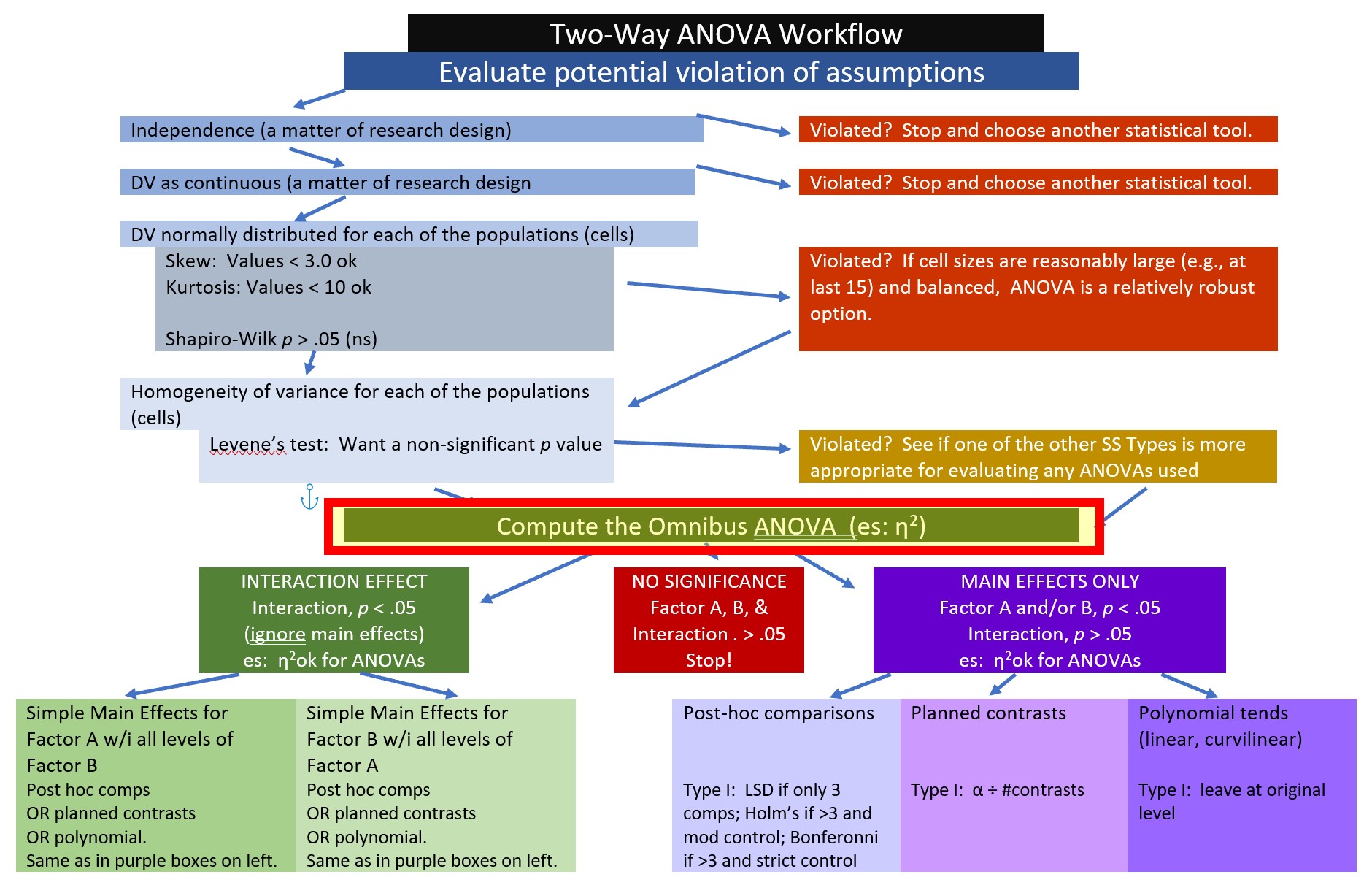

Here’s where we are in the workflow.

When we run the two-way ANOVA we will be looking for several effects:

- main effects for each predictor, and

- the interaction effect.

It is possible that all effects will be significant, none will be significant, or some will be significant. The interaction effect always takes precedence over the main effect because it lets us know there is a more nuanced/complex result.

In the code below, the type argument is used to specify the type of sums of squares that are used. Type II is the rstatix::anova_test()’s default and is what I will use in this demonstration. It will yield identical results as type=1 when data are balanced (i.e., cell sizes are equal). In specifying the ANOVA, order of entry matters if you choose type=1. In that case, if there are distinctions between independent variable and moderator, enter the independent variable first because it will claim the most variance. I provide more information on these options related to types of sums of squares calculations near the end of the chapter.

omnibus2w <- rstatix::anova_test(Ramdhani_df, Negative ~ Rater*Photo, type="2", detailed=TRUE)

omnibus2w## ANOVA Table (type II tests)

##

## Effect SSn SSd DFn DFd F p p<.05 ges

## 1 Rater 12.238 79.341 2 105 8.098 0.0005360 * 0.134

## 2 Photo 14.619 79.341 1 105 19.346 0.0000262 * 0.156

## 3 Rater:Photo 8.609 79.341 2 105 5.696 0.0040000 * 0.098Let’s write the F strings from the above table.

- Rater main effect: \(F[2, 105] = 8.098, p < 0.001, \eta ^{2} = 0.134\)

- Photo stimulus main effect: \(F[1, 105] = 19.346, p < 0.001, \eta ^{2} = 0.156\)

- Interaction effect: \(F[2, 105] = 5.696, p = 0.004, \eta ^{2} = 0.098\)

Eta squared (represented in the “ges” column of ouput) is one of the most commonly used measures of effect. It refers to the proportion of variability in the DV/outcome variable that can be explained in terms of the IVs/predictors. Conventionally, values of .01, .06, and .14 are considered to be small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively.

You may see different values (.02, .13, .26) offered as small, medium, and large – these values are used when multiple regression is used. A useful summary of effect sizes, guide to interpreting their magnitudes, and common usage can be found here (Watson, 2020).

The formula for \(\eta ^{2}\) is straightforward:

\[\eta ^{2}=\frac{SS_{M}}{SS_{T}}\]

Before moving to follow-up, an APA style write-up of the omnibus might read like this:

8.5.2.1 APA write-up of the omnibus results

A 3 X 2 ANOVA was conducted to evaluate the effects of rater ethnicity (3 levels, Dayaknese, Madurese, Javanese) and photo stimulus (2 levels, Dayaknese on Madurese,) on negative reactions to the photo stimuli.

Computing sums of squares with a Type II approach, the results for the ANOVA indicated a significant main effect for ethnicity of the rater (\(F[2, 105] = 8.098, p < 0.001, \eta ^{2} = 0.134\)), a significant main effect for photo stimulus, (\(F[1, 105] = 19.346, p < 0.001, \eta ^{2} = 0.156\)), and a significant interaction effect (\(F[2, 105] = 5.696, p = 0.004, \eta ^{2} = 0.098\)).

8.5.3 Follow-up to a Significant Interaction Effect

In factorial ANOVA we are interested in main effects and interaction effects. When the result is explained by a main effect, then there is a consistent trend as a function of a factor (e.g., Madurese raters had consistently higher Negative evaluations, irrespective of stimulus). In an interaction effect, the results are more complex (e.g., the ratings across the stimulus differed for the three groups of raters).

There are a variety of strategies to follow-up a significant interaction effect. In this lesson, I demonstrate the two I believe to be the most useful in the context of psychologists operating within the scientist-practitioner-advocacy context. I provide additional examples in the appendix.

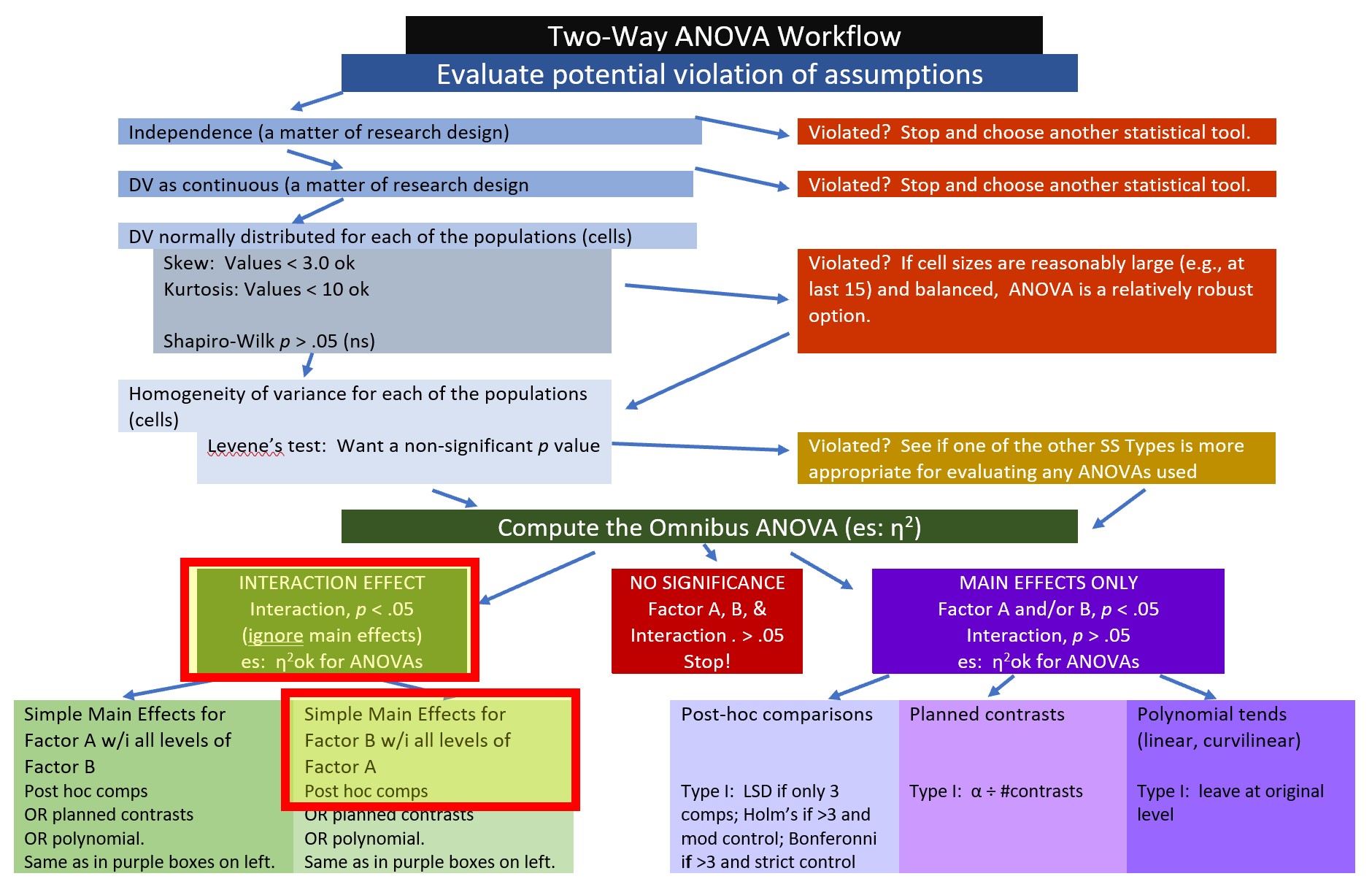

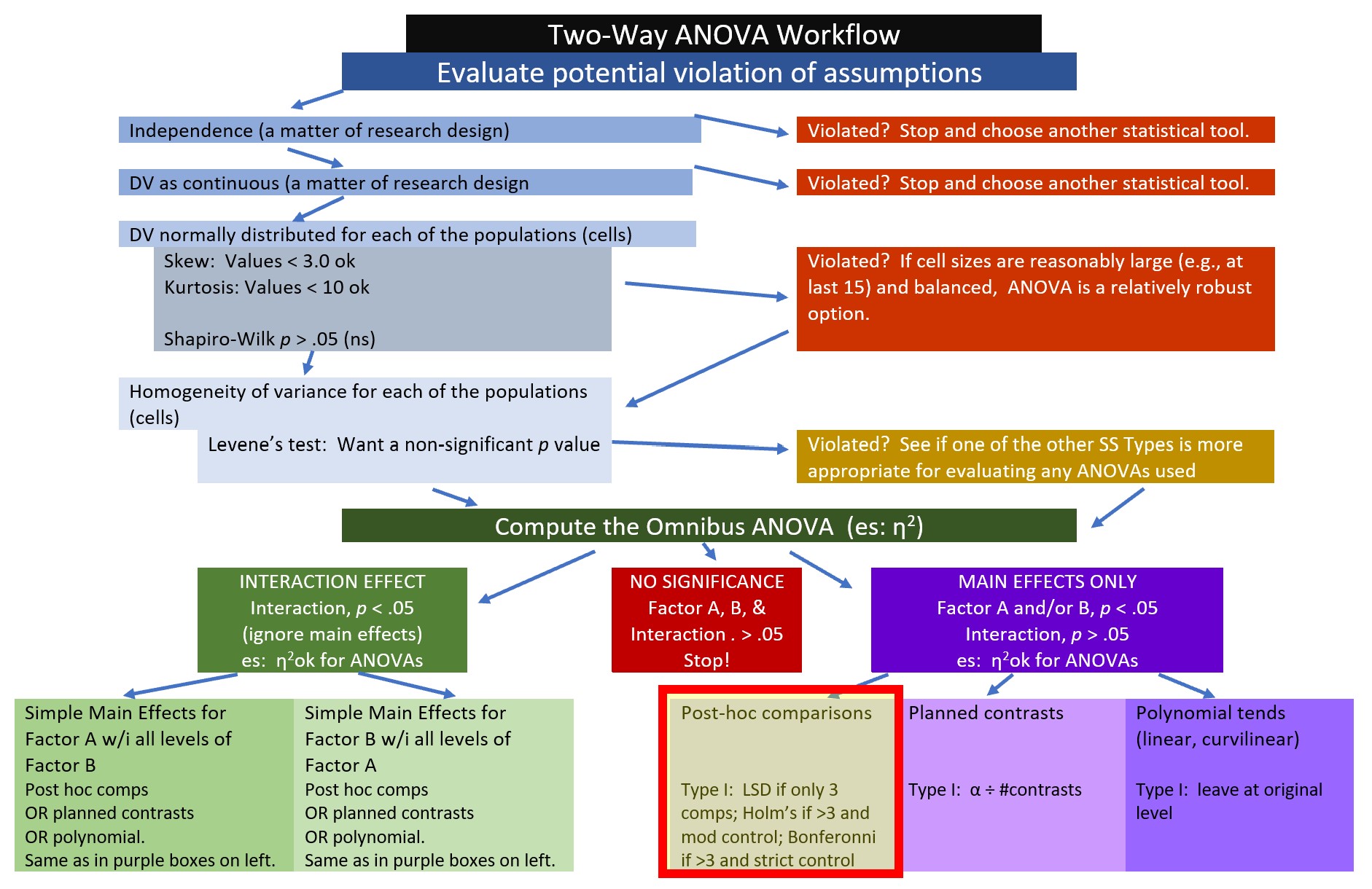

When an interaction effect is significant (irrespective of the significance of one or more main effects), examination of simple main effects is a common statistical/explanatory approached that is used. The Two-Way ANOVA Workflow shows where we are in this process. Our research vignette is a 3 x 2 ANOVA. The first factor, ethnicity, has three levels (Dayaknes, Javanese, Madurese) and the second factor, photo stimulus, has two levels (Dayaknese, Madurese). When we conduct simple main effects, we evaluate one factor within the levels of the other factor. The number of levels in each factor changes the number of steps (i.e., the complexity) in the analysis.

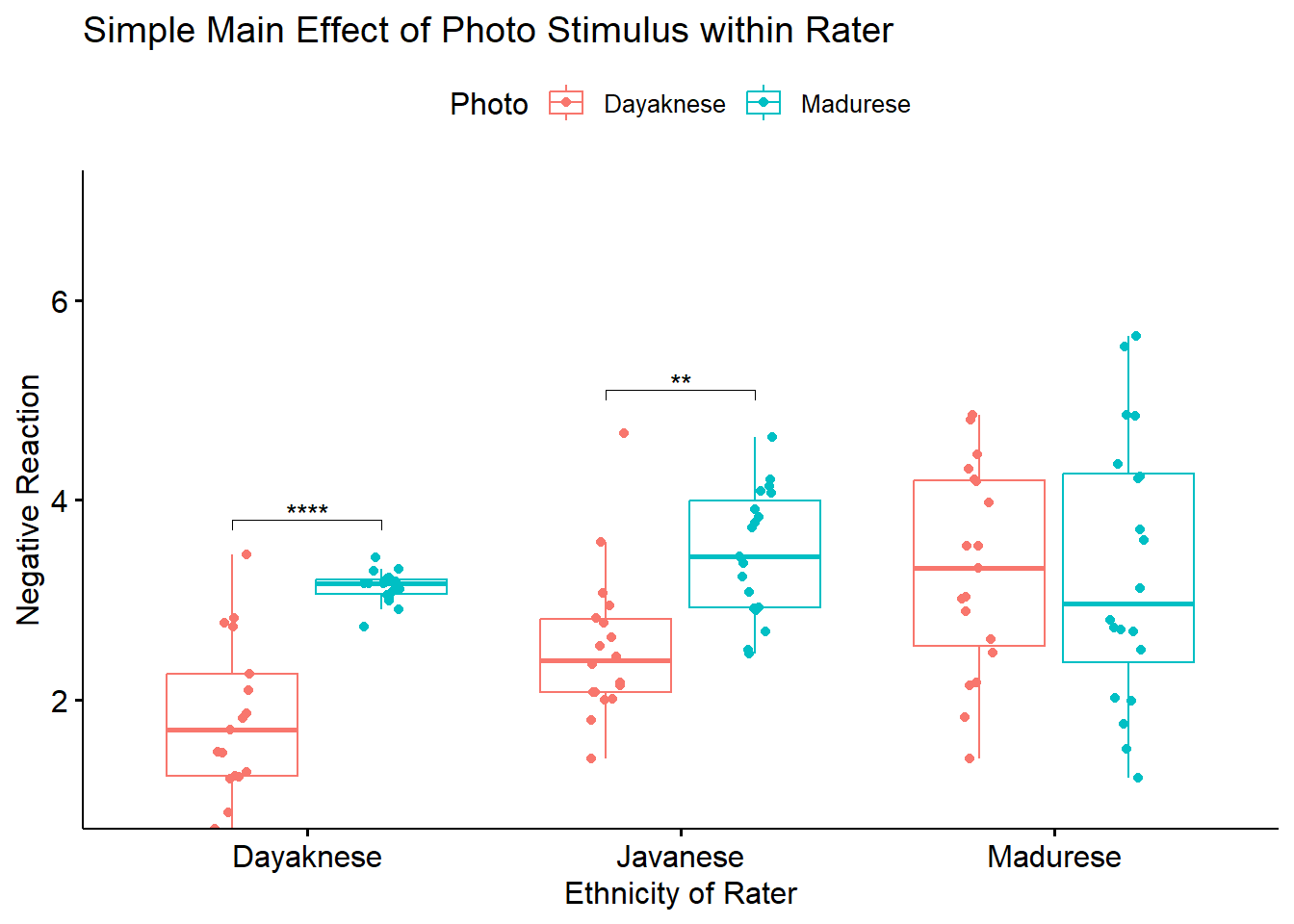

When I am analyzing the simple main effect of photo stimulus (two levels) within ethnicity of the rater (three levels), I only need a one-step procedure that will conduct pairwise comparisons of the negative evaluating of the photo stimulus for the Dayaknese, Javanese, and Madurese raters, separately (while controlling for Type I error). Traditionally, researchers will follow with three, separate, one-way ANOVAs. However, any procedure (e.g., t-tests, pairwise comparisons) that will make these pairwise comparisons is sufficient.

When I am analyzing the simple main effect of ethnicity of the rater (three levels) within photo stimulus (two levels), I will need a two-step process. The first step will require the one-way ANOVA to determine, first, if there were statistically significant differences within the photo stimulus (e.g., Were there differences between Dayaknese, Javanese, and Madurese raters when viewing the Dayaknese photos?). If there were statistically significant differences, we follow up with an analysis of pairwise comparisons.

Although I will demonstrate both rater ethnicity within photo stimulus and photo stimulus within rater ethnicity in this lesson, we will choose only one for the write-up of results.

8.5.3.1 Planning for the management of Type I Error

Controlling for Type I error can depend, in part, on the design of the follow-up tests that are planned, and the number of pairwise comparisons that follow.

In the first option, the examination of the simple main effect of photo stimulus within ethnicity of rater results in only three pairwise comparisons. In this case, I will use the traditional Bonferroni. Why? Because there are only three post omnibus analyses, its more restrictive control is less likely to be problematic.

In the second option, the examination of the simple main effect of ethnicity of the rater within photo stimulus results in the potential comparison of six pairwise comparisons. If we used a traditional Bonferroni and divided .05/6, the p value for each comparison would need to be less than 0.008. Most would agree that this is too restrictive.

## [1] 0.008333333The Holm’s sequential Bonferroni (Green & Salkind, 2017c) offers a middle-of-the-road approach (not as strict as .05/6 with the traditional Bonferroni; not as lenient as “none”) to managing Type I error.

If we were to hand-calculate the Holms, we would rank order the p values associated with the six comparisons in order from lowest (e.g., 0.000001448891) to highest (e.g., 1.000). The first p value is evaluated with the most strict criterion (.05/6; the traditional Bonferonni approach). Then, each successive comparison calculates the p value by using the number of remaining comparisons as the denominator (e.g., .05/5, .05/4, .05/3). As the p values increase and the alpha levels relax, there will be a cut-point where remaining comparisons are not statistically significant. Luckily, most R packages offer the Holm’s sequential Bonferroni as an option. The algorithm in the package rearranges the mathematical formula and produces a p value that we can interpret according to the traditional values of \(p < .05, p < .01\) and \(p < .001\). I will demonstrate use of Holm’s in the examination of the simple main effect of ethnicity of rater within photo stimulus.

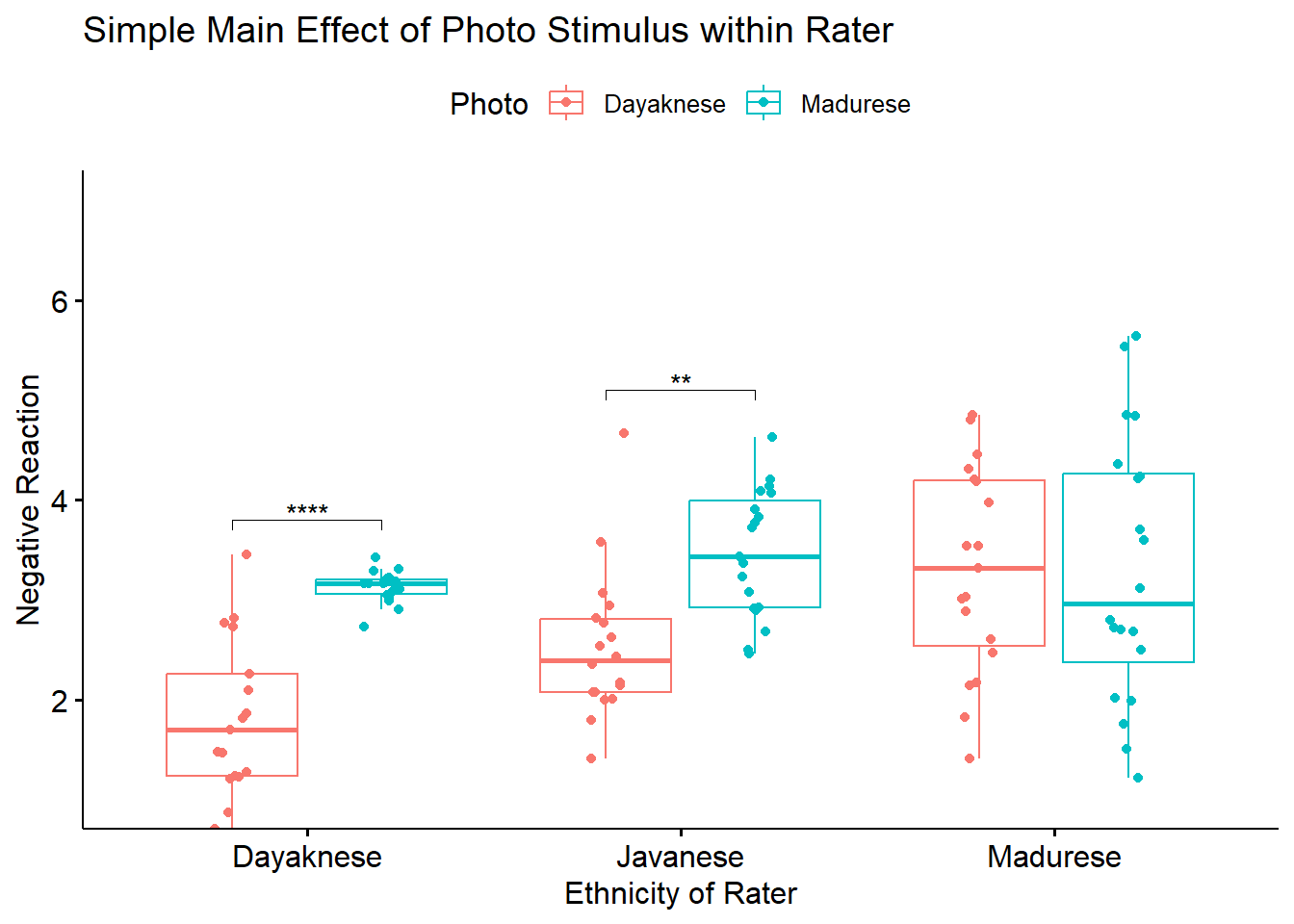

8.5.3.2 Option #1 the simple main effect of photo stimulus within ethnicity of the rater

In the examination of the simple main effect of photo stimulus within ethnicity of the rater our goal is to compare the:

- Dayaknese raters’ negative evaluation of the Dayaknese and Madurese photos,

- Javanese raters’ negative evaluation fo the Dayaknese and Madurese photos, and

- Madurese raters’ negative evaluation of the Dayaknese and Madurese photos.

Thus, we only need three, pairwise comparisons. I will demonstrate two ways to conduct these analyses. Here’s where we are in the two-way ANOVA workflow

Separate one-way ANOVAs are a traditional option for this evaluation. Using dplyr::group_by() we can efficiently calculate the three ANOVAs by the grouping variable, Rater. One advantage of separate one-way ANOVAs is that they each have their own error term and that this can help mitigate problems associated with violation of the homogeneity of variance assumption (Kassambara, n.d.-a).

Note that in this method there is no option for controlling Type I error. Thus, we would need to do it manually. The traditional Bonferroni involves dividing family-wise error (traditionally \(p < .05\)) by the number of follow-up comparisons. In our case \(.05/3 = .017\).

## # A tibble: 3 × 8

## Rater Effect DFn DFd F p `p<.05` ges

## * <fct> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <dbl>

## 1 Dayaknese Photo 1 33 50.4 0.0000000395 "*" 0.604

## 2 Javanese Photo 1 35 17.2 0.000205 "*" 0.329

## 3 Madurese Photo 1 37 0.0000762 0.993 "" 0.00000206The APA style write-up will convey what we have found using this traditional approach:

To explore the interaction effect, we followed with a test of the simple main effect of photo stimulus within the ethnicity of the rater. That is, with separate one-way ANOVAs (chosen, in part, to mitigate violation of the homogeneity of variance assumption (Kassambara, n.d.-a)) we examined the effect of the photo stimulus within the Dayaknese, Madurese, and Javanese groups. To control for Type I error across the three simple main effects, we set alpha at .017 (.05/3). Results indicated significant differences for Dayaknese (\(F [1, 33] = 50.404, p < 0.001, \eta ^{2} = 0.604\)) and Javanese ethnic groups \((F [1, 35] = 17.183, p < 0.001, \eta ^{2} = 0.329)\), but not for the Madurese ethnic group \((F [1, 37] < 0.001, p = .993, \eta ^{2} < .001)\). As illustrated in Figure 1, the Dayaknese and Javanese raters both reported stronger negative reactions to the Madurese. The differences in ratings for the Madurese were not statistically significantly different. In this way, the rater’s ethnic group moderated the relationship between the photo stimulus and negative reactions.

The rstatix::emmeans_test() offers an efficient alternative to this pairwise analysis that will (a) automatically control for Type I error and (b) integrate well into a figure. Note that this function is a wrapper to functions in the emmeans package. If you haven’t already, you will need to install the emmeans package. For each, the resulting test statistic is a t.ratio. The result of this t-test will be slightly different than an independent sample t-test because it is based on estimated marginal means (i.e., means based on the model, not directly on the data). We will spend more time with estimated marginal means in the ANCOVA lesson.

In the script below, we will group the dependent variable by Rater and then conduct pairwise comparisons. Note that I have requested that that the traditional Bonferroni be used to manage Type I error. We can see these adjusted p values in the output.

library(tidyverse)

pwPHwiETH <- Ramdhani_df%>%

group_by(Rater)%>%

rstatix::emmeans_test(Negative ~ Photo, detailed = TRUE, p.adjust.method = "bonferroni")

pwPHwiETH## # A tibble: 3 × 15

## Rater term .y. group1 group2 null.value estimate se df conf.low

## * <fct> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 Dayaknese Photo Negati… Dayak… Madur… 0 -1.31 0.294 105 -1.89

## 2 Javanese Photo Negati… Dayak… Madur… 0 -0.941 0.286 105 -1.51

## 3 Madurese Photo Negati… Dayak… Madur… 0 0.00334 0.278 105 -0.549

## # ℹ 5 more variables: conf.high <dbl>, statistic <dbl>, p <dbl>, p.adj <dbl>,

## # p.adj.signif <chr>Not surprisingly, our results are quite similar. I would report them this way:

To explore the interaction effect, we followed with a test of the simple main effect of photo stimulus within the ethnicity of the rater. Specifically, we conducted pairwise comparisons between the groups using the estimated marginal means. We specified the Bonferroni method for managing Type I error. Results suggested statistically significant differences differences for the Dayaknese (\(M_diff = -1.312, t[105] = -4.461, p < 0.001\)) and Javanese ethnic groups (\(M_diff = -0.941, t[105] = -3.291, p < 0.001\)) but not for the Madurese ethnic group (\(M_diff = 0.003, t[105] = 0.0121, p = 0.990\)). As illustrated in Figure 1, the Dayaknese and Javanese raters both reported stronger negative reactions to the Madurese. The differences in ratings for the Madurese were not statistically significantly different. In this way, the rater’s ethnic group moderated the relationship between the photo stimulus and negative reactions.

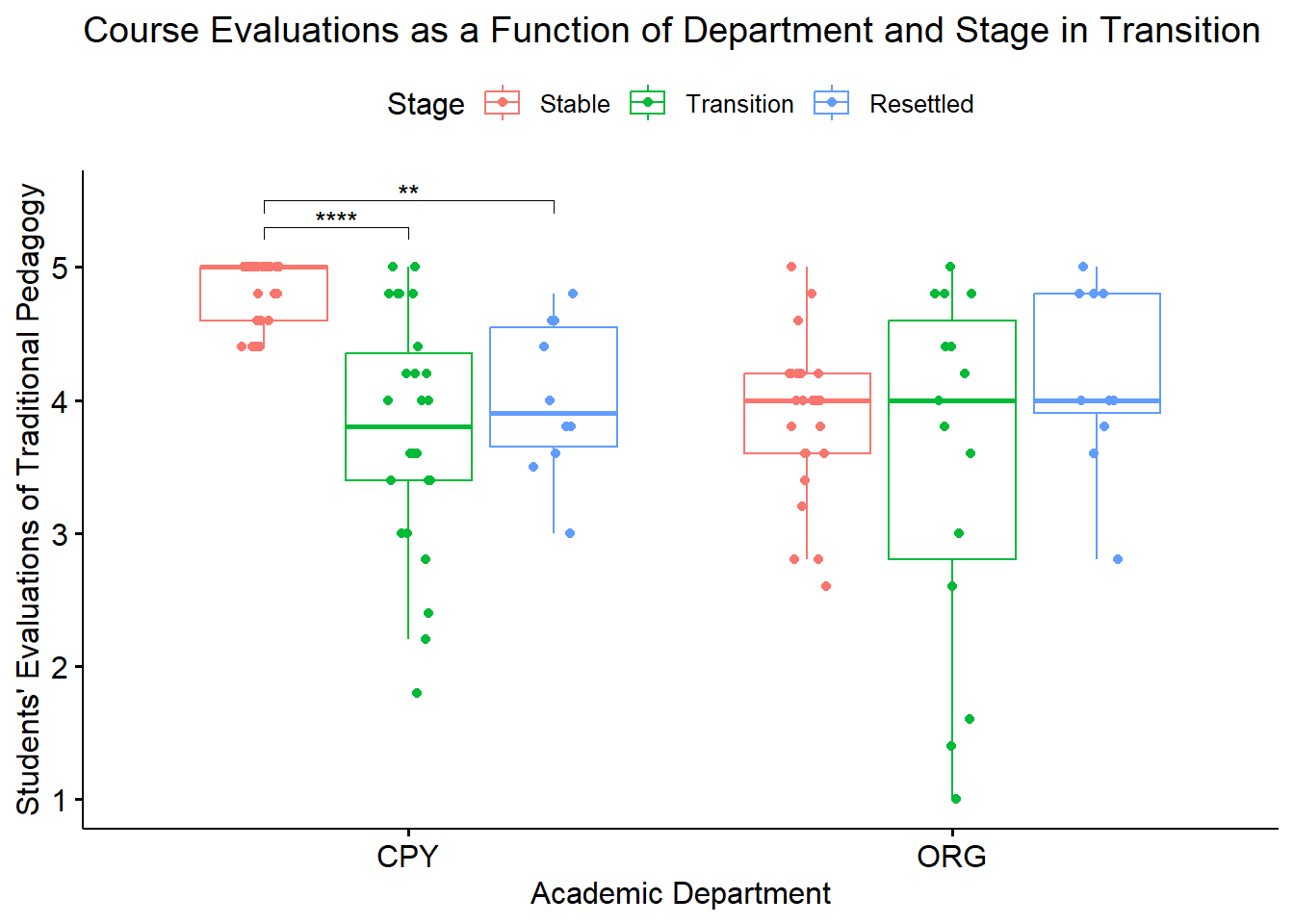

Because we used the rstatix functions, we can easily integrate them into our ggpubr::ggboxplot(). Let’s first re-run the version of the boxplot where “Rater” is on the x-axis (and, is therefore our grouping variable). Because I want the data to be as true-to-scale as possible, I have added the full range of the y axis through the ylim argument. In order to update the ggboxplot, we will need to save it as an option. My object name represents the “PHoto within Ethnicity” simple main effect.

boxPHwiETH <- ggpubr::ggboxplot(Ramdhani_df, x = "Rater", y = "Negative", color = "Photo",xlab = "Ethnicity of Rater", ylab = "Negative Reaction", add = "jitter", title = "Simple Main Effect of Photo Stimulus within Rater", ylim = c(1, 7))

pwPHwiETH <- pwPHwiETH %>% rstatix::add_xy_position(x = "Rater") #x should be whatever the variable was used in the group_by argument

boxPHwiETH <- boxPHwiETH +

ggpubr::stat_pvalue_manual(pwPHwiETH, label = "p.adj.signif", tip.length = 0.02, hide.ns = TRUE, y.position = c(3.8, 5.1))

boxPHwiETH

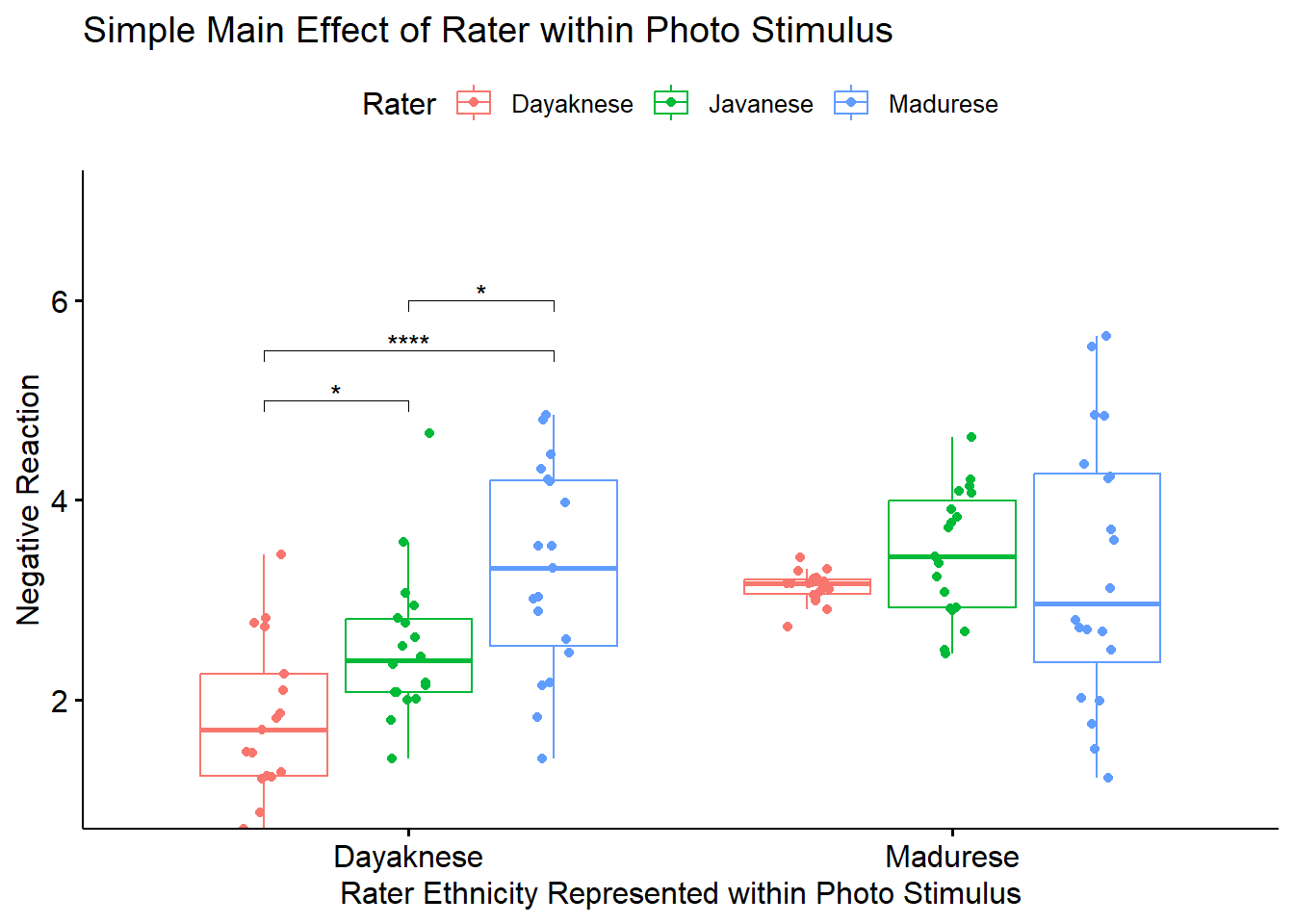

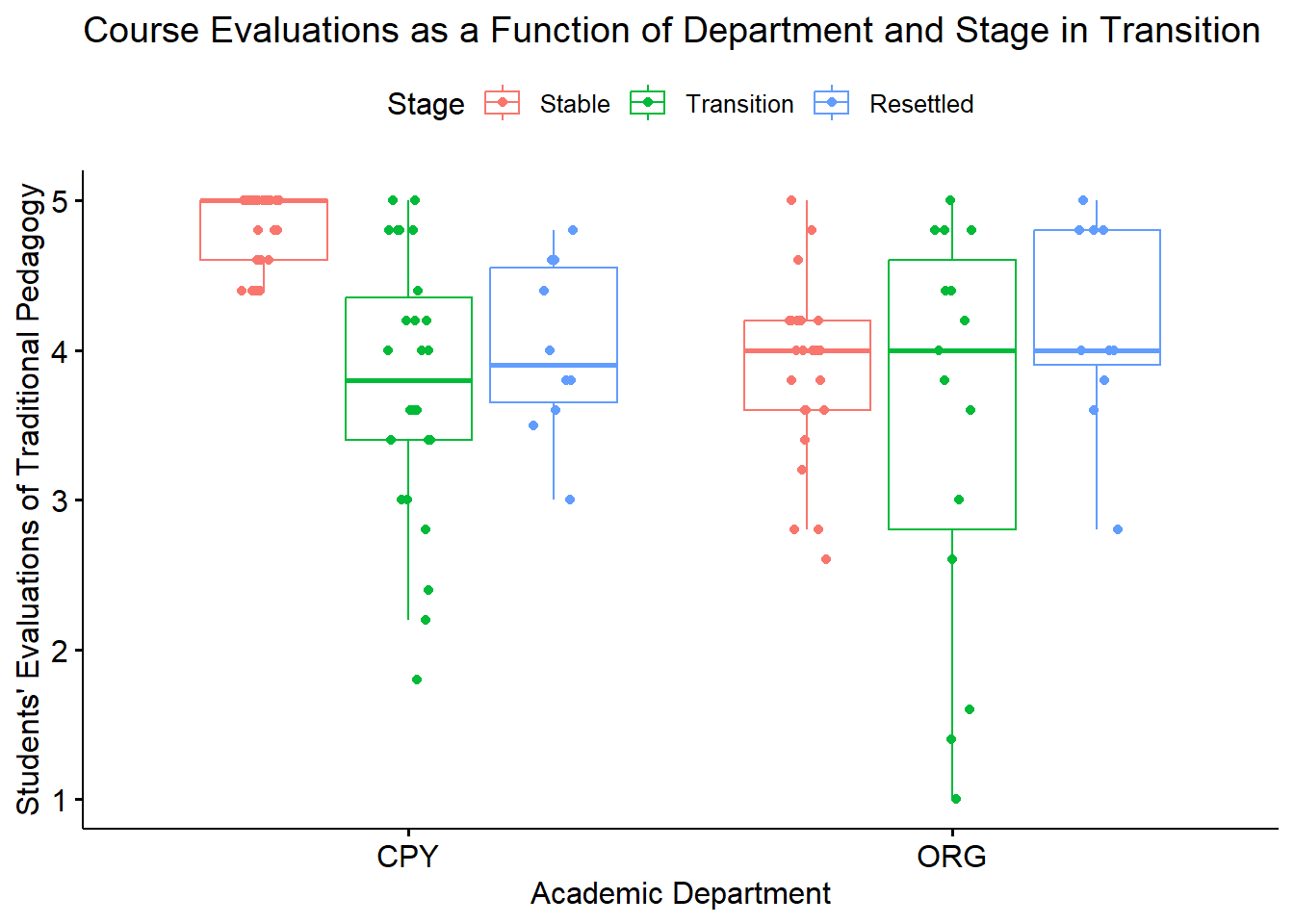

8.5.3.3 Option #2 the simple main effect of ethnicity of rater within photo stimulus.

In the examination of the simple main effect of rater ethnicity photo stimulus our goal is to compare:

- Dayaknese, Javanese, and Madurese negative evaluations of the Dayaknese photos, and

- Dayaknese, Javanese, and Madurese negative evaluations of the Maudurese photos.

Consequently, we will need a two-staged evaluation. First, we will conduct separate one-way ANOVAs. Second, we will follow-up with pairwise comparisons.

Let’s start with the one-way ANOVAs. Using dplyr::group_by() we can efficiently calculate the three ANOVAs by the grouping variable, Photo. One advantage of separate one-way ANOVAs is that they each have their own error term and that this can help mitigate problems associated with violation of the homogeneity of variance assumption (Kassambara, n.d.-a).

Note that in this method there is no option for controlling Type I error. Thus, we would need to do it manually. The traditional Bonferroni involves dividing family-wise error (traditionally \(p < .05\)) by the number of follow-up comparisons. In our case \(.05/2 = .025\).

## # A tibble: 2 × 8

## Photo Effect DFn DFd F p `p<.05` ges

## * <fct> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <dbl>

## 1 Dayaknese Rater 2 51 13.3 0.0000221 "*" 0.343

## 2 Madurese Rater 2 54 0.679 0.512 "" 0.025The APA style write-up will convey what we have found (so far) using this approach:

To explore the interaction effect, we followed with a test of the simple main effect of ethnicity of the rater within the photo stimulus. We began with separate one-way ANOVAs (chosen, in part, to mitigate violation of the homogeneity of variance assumption (Kassambara, n.d.-a)). To control for Type I error across the two simple main effects, we set alpha at .025 (.05/2). Results indicated significant differences for Dayaknese photo (\(F [2, 51] = 13.325, p < 0.001, \eta ^{2} = 0.343\)) but not for the Madurese photo \((F [2, 54] = 0.679, p = 0.512, \eta ^{2} = 0.025)\).

Results suggest that there are differences within the Dayaknese group, yet because there are three groups, we cannot know with certainty where there are statistically significant difference. As before, we can use the rstatix::emmeans_test() to conduct the pairwise analysis. This function will (a) automatically control for Type I error and (b) integrate well into a figure. For each comparison, the resulting test statistic is a t.ratios. The result of this t-test will be slightly different than an independent sample t-test because it is based on estimated marginal means (i.e., means based on the model, not directly on the data). We will spend more time with estimated marginal means in the ANCOVA lesson.

In the script below, we will group the dependent variable by Photo and then conduct pairwise comparisons. Note that I have requested that that the Holm’s sequential Bonferroni be used to manage Type I error. We can see these adjusted p values in the output.

pwETHwiPH <- Ramdhani_df%>%

dplyr::group_by(Photo)%>%

rstatix::emmeans_test(Negative ~ Rater, p.adjust.method = "holm")

pwETHwiPH## # A tibble: 6 × 10

## Photo term .y. group1 group2 df statistic p p.adj p.adj.signif

## * <fct> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr>

## 1 Dayakn… Rater Nega… Dayak… Javan… 105 -2.40 1.81e-2 1.81e-2 *

## 2 Dayakn… Rater Nega… Dayak… Madur… 105 -5.11 1.45e-6 4.35e-6 ****

## 3 Dayakn… Rater Nega… Javan… Madur… 105 -2.72 7.69e-3 1.54e-2 *

## 4 Madure… Rater Nega… Dayak… Javan… 105 -1.17 2.43e-1 7.29e-1 ns

## 5 Madure… Rater Nega… Dayak… Madur… 105 -0.595 5.53e-1 1 e+0 ns

## 6 Madure… Rater Nega… Javan… Madur… 105 0.601 5.49e-1 1 e+0 nsVery consistent with the one-way ANOVAs, we see that there were significant rater differences in the evaluation of the Dayaknese photo, but not for the Madurese photo. Further, in the rating of the Dayaknese photo, there were statistically significant differences between all three comparisons of ethnic groups. The p-values remained statistically significant with the adjustment of the Holm’s.

For a quick demonstration of differences in managing Type I error, I wil replace “holm” with “bonferroni.” Here, we will see the more restrictive result, where one of the previously significant comparisons drops out. Note that I am not saving this results as an object – I don’t want it to interfere with our subsequent analyses

#demonstration of the more restrictive bonferroni approach to managing Type I error

Ramdhani_df%>%

dplyr::group_by(Photo)%>%

rstatix::emmeans_test(Negative ~ Rater, p.adjust.method = "bonferroni")## # A tibble: 6 × 10

## Photo term .y. group1 group2 df statistic p p.adj p.adj.signif

## * <fct> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr>

## 1 Dayakn… Rater Nega… Dayak… Javan… 105 -2.40 1.81e-2 5.43e-2 ns

## 2 Dayakn… Rater Nega… Dayak… Madur… 105 -5.11 1.45e-6 4.35e-6 ****

## 3 Dayakn… Rater Nega… Javan… Madur… 105 -2.72 7.69e-3 2.31e-2 *

## 4 Madure… Rater Nega… Dayak… Javan… 105 -1.17 2.43e-1 7.29e-1 ns

## 5 Madure… Rater Nega… Dayak… Madur… 105 -0.595 5.53e-1 1 e+0 ns

## 6 Madure… Rater Nega… Javan… Madur… 105 0.601 5.49e-1 1 e+0 nsLet’s create a figure that reflects the results of this simple main effect of rater ethnicity within photo stimulus. As before, we start with the corresponding figure where “Photo” is on the x-axis.

boxETHwiPH <- ggpubr::ggboxplot(Ramdhani_df, x = "Photo", y = "Negative", color = "Rater",xlab = "Rater Ethnicity Represented within Photo Stimulus", ylab = "Negative Reaction", add = "jitter", title = "Simple Main Effect of Rater within Photo Stimulus", ylim = c(1, 7))

pwETHwiPH <- pwETHwiPH %>% rstatix::add_xy_position(x = "Photo") #x should be whatever the variable was used in the group_by argument

boxETHwiPH <- boxETHwiPH +

ggpubr::stat_pvalue_manual(pwETHwiPH, label = "p.adj.signif", tip.length = 0.02, hide.ns = TRUE, y.position = c(5, 5.5, 6))

boxETHwiPH

Here’s how I would update the APA style reporting of results:

To explore the interaction effect, we followed with a test of the simple main effect of ethnicity of the rater within the photo stimulus. We began with separate one-way ANOVAs (chosen, in part, to mitigate violation of the homogeneity of variance assumption (Kassambara, n.d.-a)). To control for Type I error across the two simple main effects, we set alpha at .025 (.05/2). Results indicated significant differences for Dayaknese photo (\(F [2, 51] = 13.325, p < 0.001, \eta ^{2} = 0.343\)) but not for the Madurese photo \((F [2, 54] = 0.679, p = 0.512, \eta ^{2} = 0.025)\). We followed up significant one-way ANOVA with pairwise comparisons between the groups using the estimated marginal means. We specified the Holm’s sequential Bonferroni for managing Type I error. Regarding evaluation of the Dayaknese photo, results suggested statistically significant differences in all combinations of raters. As shown in Figure 1, the Dayaknese raters had the lowest ratings, followed by Javanese raters, and then Madurese raters. Consistent with the non-significant one-way ANOVA evaluating ratings of the Madurese photo, there were no statistically significant differences for raters. Results of these tests are presented in Table 1.

8.5.3.4 Options #3 through k

There are seemingly infinite approaches to analyzing significant interaction effects. I am frequently asked, “But what about _____?” And “Do you have an example of ____?” In prior versions of this lesson, I included a few more examples in this section of follow-up to a significant interaction effect. However, in an effort to reduce the cognitive load of the chapter and stay focused on the primary learning goals I have relocated some of these to the appendix At the time of this update, there are worked examples that highlight:

- Orthogonal contrast-coding

- All possible post hoc comparisons

- Polynomial trends

If, as a reader, you have recommendations for more specific examples, please suggest them using the contact information provided at the beginning of the OER.

8.5.4 Investigating Main Effects

We now focus on the possibility that there might be significant main effects, but a non-significant interaction effect. We only interpret main effects when there is a non-significant interaction effect. Why? Because in the presence of a significant interaction effect, the main effect will not tell a complete story. If we didn’t specify a correct model, we still might have an incomplete story. But that’s another issue.

Here’s where we are on the workflow.

Recall that main effects are the marginal means – that is the effects of factor A collapsed across all the levels of factor B.

If the main effect has only two levels (e.g., the ratings of the Dayaknese and Madurese photos):

- the comparison was already ignoring/including all levels of the rater ethnicity factor (Dayaknese, Madurese, Javanese),

- it was only a comparison of two cells (Dayaknese rater, Madurese rater), therefore

- there is no need for further follow-up.

In the case of our specific research vignette, we learned from the omnibus test that the Photo main effect was statistically significant (\(F[1, 105] = 19.346, p < 0.001, \eta ^{2} = 0.156\)).This means that we know there are statistically significant differences between ratings of Dayaknese and Madurese photos overall.

## item group1 vars n mean sd median trimmed mad

## Negative1 1 Dayaknese 1 54 2.574926 1.0434646 2.449 2.516386 0.9206946

## Negative2 2 Madurese 1 57 3.300211 0.8709631 3.166 3.279745 0.6671700

## min max range skew kurtosis se

## Negative1 0.706 4.854 4.148 0.4699817 -0.5548515 0.1419975

## Negative2 1.211 5.641 4.430 0.3501228 0.5814430 0.1153619A quick review of the descriptive statistics, aggregated by photo stimulus indicates that, overall, Madurese photos were evaluated more negatively.

If the main effect has three or more levels (e.g,. ethnicity of rater with Dayaknese, Madurese, Javanese levels), then we follow-up with one or more of the myriad of options. I tend to focus on three:

- planned contrasts

- posthoc comparisons (all possible cells)

- polynomial

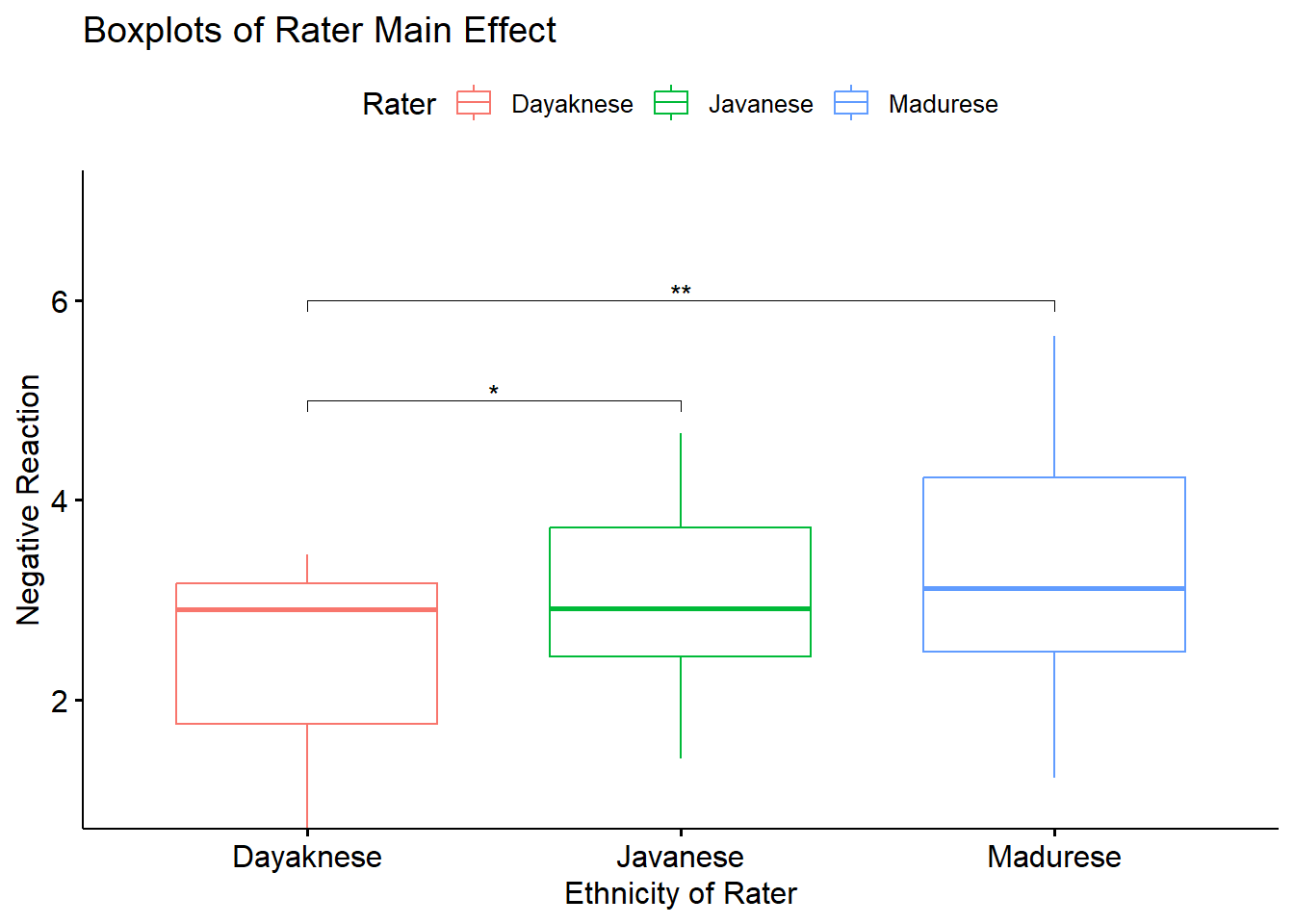

From our omnibus evaluation, our rater main effect was \(F[2, 105] = 8.098, p < .001, \eta ^{2} = 0.134\). I will demonstrate how to do each as follow-up to a pretend scenario where a main effect (but not the interaction effect) had been significant. In fact, our follow-up of Rater main effects will be quite similar to the manner in which we followed up the significant omnibus in the one-way ANOVA lesson.

Here’s what would happen if we simply ran a one-way ANOVA.

## ANOVA Table (type II tests)

##

## Effect DFn DFd F p p<.05 ges

## 1 Rater 2 108 6.426 0.002 * 0.106Results of a one-way ANOVA evaluating negative reaction to photos of members of Dayaknese and Madurese ethnic groups indicate a statistically differences as a function of the ethnicity of the rater (\(F[2, 108] = 6.426, p = 0.002, \eta^2 = 0.106\))

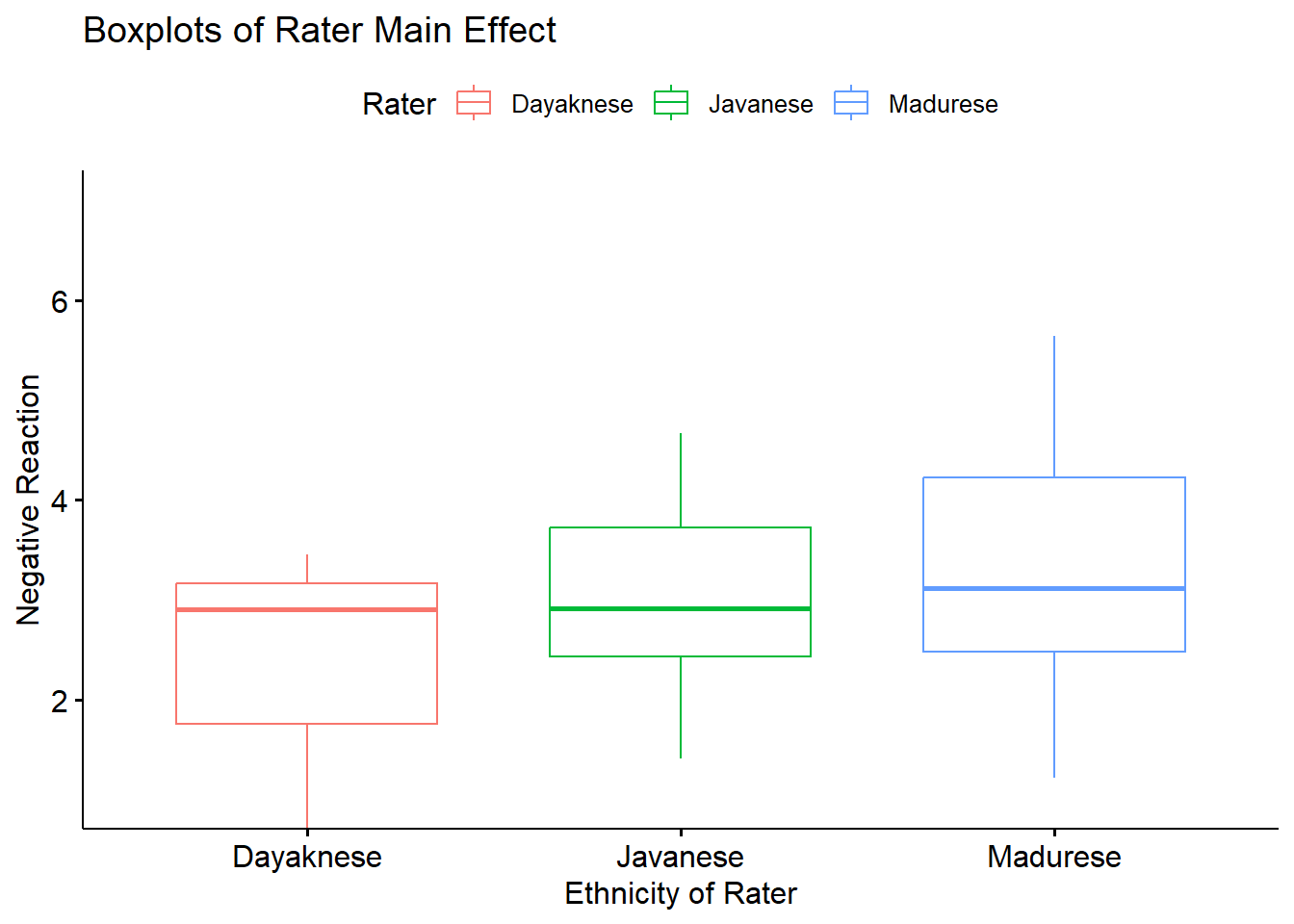

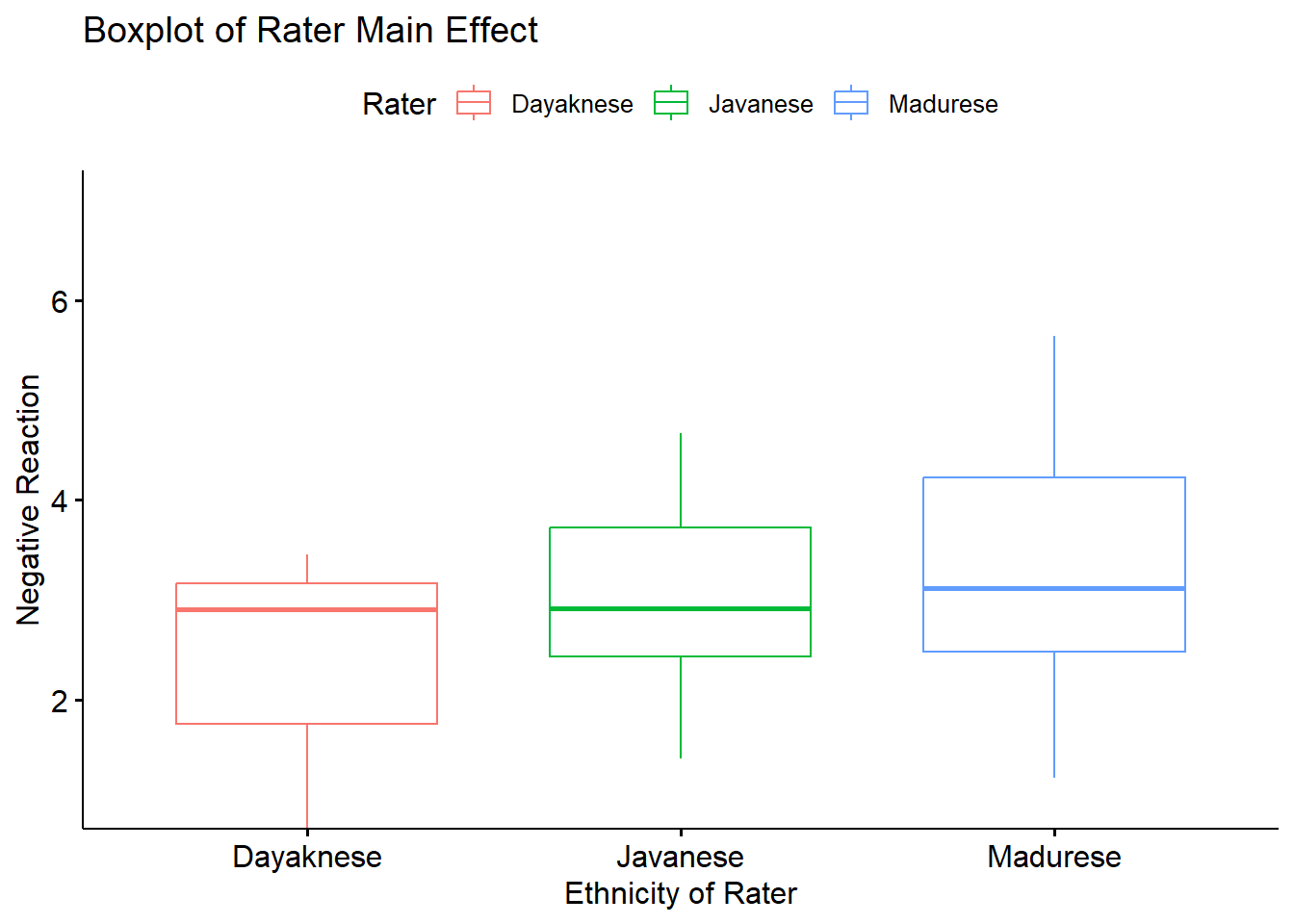

A boxplot representing this main effect may help convey how the main effect of Rater (collapsed across Photo) is different than an interaction effect.

box_RaterMain <- ggpubr::ggboxplot(Ramdhani_df, x = "Rater", y = "Negative", xlab = "Ethnicity of Rater", ylab = "Negative Reaction", color = "Rater", ylim = c(1, 7), title = "Boxplots of Rater Main Effect")

box_RaterMain

8.5.4.1 Option #1 post hoc paired comparisons

An easy possibility is to follow-up with all possible post hoc pairwise comparisons. Here is a reminder of our location on the workflow.

Post hoc, pairwise comparisons are:

- used for exploratory work when no firm hypotheses were articulated a priori,

- used to compare the means of all combinations of pairs of an experimental condition, and

- less powerful than planned comparisons because more strict criterion for significance should be used.

By specifying the formula of the ANOVA, the rstatix::t_test() function will provide comparisons of all possible combinations. The arguments in the code mirror those we used for the omnibus. Note that I am saving the results as an object. We will use this object (“ttest”) later when we create an accompanying figure.

We will request the traditional Bonferroni using the p.adjust.method. The rstatix::t_test() offers multiple options for adjusting the p values.

RaterMain_ttest <- rstatix::t_test(Ramdhani_df, Negative ~ Rater, p.adjust.method="bonferroni", detailed=TRUE)

RaterMain_ttest## # A tibble: 3 × 17

## estimate estimate1 estimate2 .y. group1 group2 n1 n2 statistic p

## * <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <chr> <int> <int> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 -0.515 2.49 3.01 Negati… Dayak… Javan… 35 37 -2.59 0.012

## 2 -0.807 2.49 3.30 Negati… Dayak… Madur… 35 39 -3.39 0.001

## 3 -0.292 3.01 3.30 Negati… Javan… Madur… 37 39 -1.25 0.214

## # ℹ 7 more variables: df <dbl>, conf.low <dbl>, conf.high <dbl>, method <chr>,

## # alternative <chr>, p.adj <dbl>, p.adj.signif <chr>The estimate column provide the mean difference between the two levels of the independent different. The estimate1/group1 and estimate2/group2 columns provide those means and identify the group levels. The statistic column provides the value of the t-test.

The p value is the unadjusted p-value, it will usually be “more significant” (i.e., a lower value) than the p.adj value associated with the strategy for managing Type I error that we specified in our code. The column p.adj.signif provides symbolic notation associated with the p.adj value. In this specific case we specified the traditional Bonferroni as the adjusted p value.

An APA style results section of this portion of follow-up might read like this:

We followed significant the rater main effect with a series of post hoc, pairwise comparisons. We controlled for Type I error with the traditional Bonferroni adjustment. Results suggested that there were statistically significant differences between the Dayaknese and Javanese (\(M_{diff} = -0.515, p = 0.035\)) and Dayaknese and Madurese (\(M_{diff} = -0.807, p =< 0.003\)) raters, but not Javanese and Madurese rater (\(M_{diff} = -0.292, p = 0.642\)). This analysis disregards the ethnic identity displayed on the photo.

Below is an augmentation of the figure that appeared at the beginning of the chapter. We can use the objects from the omnibus tests (named, “omnibus2w”) and post hoc pairwise comparisons (“RaterMain_ttest”) to add the ANOVA string and significance bars to the figure. Although they may not be appropriate in every circumstance, such detail can assist the figure in conveying maximal amounts of information.

RaterMain_ttest <- RaterMain_ttest %>% rstatix::add_xy_position(x = "Rater")

box_RaterMain +

ggpubr::stat_pvalue_manual(RaterMain_ttest, label = "p.adj.signif", tip.length = 0.02, hide.ns = TRUE, y.position = c(5, 6))

8.5.4.2 Option #2 planned orthogonal contrasts

We generally try for orthogonal contrasts so that the partitioning of variance is independent (clean, not overlapping). Planned contrasts are a great way to do this. Here’s where we are in the workflow.

If you aren’t extremely careful about your order-of-operations in R, it can confuse objects, so I have named these contrasts c1 and c2 to remind myself that they refer to the main effect of ethnicity of the rater.

In this hypothetical scenario (remember we are pretending we are in the circumstance of a non-significant interaction effect but a significant main effect), I am:

- comparing the DV for the Javanese rater to the combined Dayaknese and Madurese raters (c1).

- comparing the DV for the Dayaknese and Madurese raters (c2).

These are orthogonal because:

- there are k - 1 comparisons, and

- once a contrast is isolated (i.e., the Javanese rater in contrast #1) it cannot be used again

- The “cake” analogy can be a useful mnemonic: once you take out a piece of the cake, you really can’t put it back in

I am not aware of rstatix functions or arguments that can complete these analyses. Therefore, we will use functions from base R. It helps to know what the default contrast codes are; we can get that information with the contrasts() function.

## Javanese Madurese

## Dayaknese 0 0

## Javanese 1 0

## Madurese 0 1Next, we set up the contrast conditions. In the code below,

- c1 indicates that the Javanese (noted as -2) are compared to the combined ratings from the Dayaknese (1) and Madurese (1)

- c2 indicates that the Dayaknese (-1) and Madurese (1) are compared; Javanese (0) is removed from the contrast.

# tell R which groups to compare

c1 <- c(1, -2, 1)

c2 <- c(-1, 0, 1)

mat <- cbind(c1,c2) #combine the above bits

contrasts(Ramdhani_df$Rater) <- mat # attach the contrasts to the variableThis allows us to recheck the contrasts.

## c1 c2

## Dayaknese 1 -1

## Javanese -2 0

## Madurese 1 1With this output we can confirm that, in contrast 1 (the first column) we are comparing the Javanese to the combined Dayaknese and Madurese. In contrast 2 (the second column) we are comparing the Dayaknese to the Madurese.

Then we run the contrast and extract the output.

##

## Call:

## aov(formula = Negative ~ Rater, data = Ramdhani_df)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -2.08813 -0.74921 0.05792 0.71482 2.34187

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 2.93283 0.09259 31.676 < 0.0000000000000002 ***

## Raterc1 -0.03712 0.06544 -0.567 0.571670

## Raterc2 0.40342 0.11345 3.556 0.000561 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.9745 on 108 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.1063, Adjusted R-squared: 0.0898

## F-statistic: 6.426 on 2 and 108 DF, p-value: 0.002307These planned contrasts show that when the Javanese raters are compared to the combined Dayaknese and Madurese raters, there was a non significant difference, \(t(108) = -0.567, p = 0.572\). However, there were significant differences between Dayaknese and Javanese raters, \(t(108) = 3.556, p < 0.001\).

An mini APA style reporting of these results might look like this:

We followed the significant rater main effect with a pair of planned, orthogonal, contrasts. The first compared Javanese raters to the combined Dayakneses and Madurese raters; there was a nonsignificant difference (\(t[108] = -0.567, p = 0.572\)). There was significant differences between Dayaknese and Javanese raters, \(t(108) = 3.556, p < 0.001\).

I am not aware of script that would effectively display this in a figure. Therefore, I would use a simple boxplot for the rater main effect.

box_RaterMain <- ggpubr::ggboxplot(Ramdhani_df, x = "Rater", y = "Negative", xlab = "Ethnicity of Rater", ylab = "Negative Reaction", color = "Rater", ylim = c(1, 7), title = "Boxplot of Rater Main Effect")

box_RaterMain

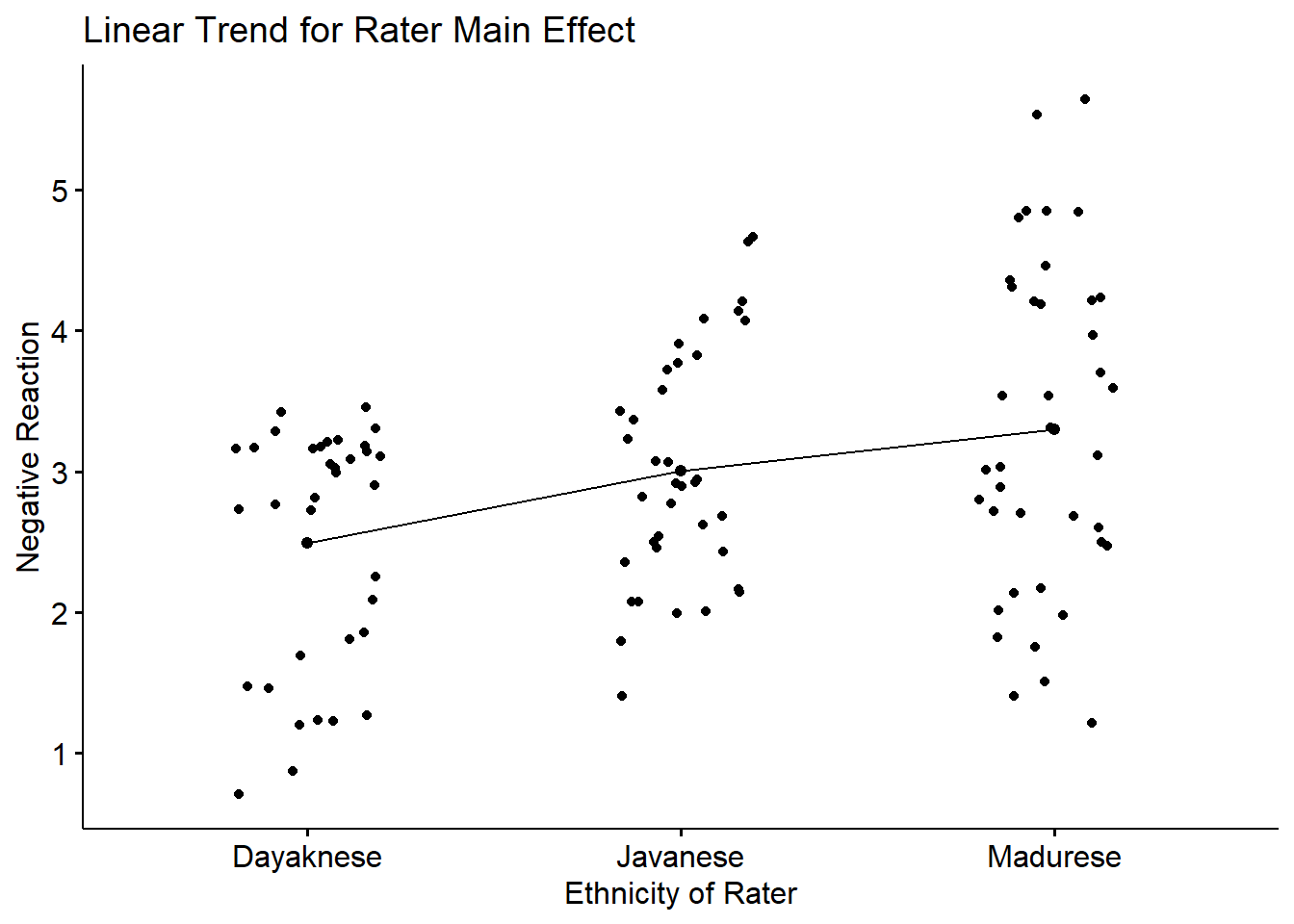

8.5.4.3 Option #3 trend/polynomial analysis

Polynomial contrasts let us see if there is a linear (or curvilinear) pattern to the data. To detect a trend, the data must be coded in an ascending order…and it needs to be a sensible comparison. Here’s where this would fall in our workflow.

Because these three ethnic groups are not ordered in the same way as would an experiment involving dosage (e.g,. placebo, lo dose, hi dose), evaluation of the polynomial trend is not really justified (even though it is statistically possible). None-the-less, I will demonstrate how it is conducted.

Because these three ethnic groups are not ordered in the same way as would an experiment involving dosage (e.g,. placebo, lo dose, hi dose), evaluation of the polynomial trend is not really justified (even though it is statistically possible). None-the-less, I will demonstrate how it is conducted.

The polynomial fits linear and curvilinear trends across levels of a factor based on how the variable is coded in R. The contrasts() function from base R will reveal ths ordering. Not surprisingly, this is the same order seen in our boxplots. In terms of the “story” of the vignette, the authors suggest that the Dayaknese are typically viewed as the ones who were victimized, the Javanese were not involved, and the Madurese have been viewed as aggressors.

## [,1] [,2]

## Dayaknese 1 -1

## Javanese -2 0

## Madurese 1 1Viewing the contrasts() output, we see that the trends (linear, quadratic) in our contrast coding will be fit across Dayaknese, Javanese, and Madurese.

In a polynomial analysis, the statistical analysis looks across the ordered means to see if they fit a linear or curvilinear shape that is one fewer than the number of levels (i.e., \(k-1\)). Because the Rater factor has three levels, the polynomial contrast checks for linear (.L) and quadratic (one change in direction) trends (.Q). If we had four levels, contr.poly() could also check for cubic change (two changes in direction). Conventionally, when more than one trend is significant, we interpret the most complex one (i.e., quadratic over linear).

To the best of my knowledge, rstatix does not offer these contrasts. We can fairly easily make these calculations in base R by creating a set of polynomial contrasts. In the prior example we specified our contrasts through coding. Here we can the contr.poly(3) function. The “3” lets R know that there are three levels in Rater The aov() function will automatically test for quadratic (one hump) and linear (straight line) trends.

contrasts(Ramdhani_df$Rater)<-contr.poly(3)

mainTrend<-aov(Negative ~ Rater, data = Ramdhani_df)

summary.lm(mainTrend)##

## Call:

## aov(formula = Negative ~ Rater, data = Ramdhani_df)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -2.08813 -0.74921 0.05792 0.71482 2.34187

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 2.93283 0.09259 31.676 < 0.0000000000000002 ***

## Rater.L 0.57052 0.16045 3.556 0.000561 ***

## Rater.Q -0.09094 0.16029 -0.567 0.571670

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.9745 on 108 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.1063, Adjusted R-squared: 0.0898

## F-statistic: 6.426 on 2 and 108 DF, p-value: 0.002307Rater.L tests the data to see if there is a significant linear trend. There is: \(t(108) = 3.556, < 0 .001\).

Rater.Q tests to see if there is a significant quadratic (curvilinear, one hump) trend. There is not: \(t(108) = -0.567, p = .572\).

Here’s how I might prepare a statement for inclusion in an write-up of APA style results:

Our follow-up to a significant main effect for Rater included a polynomial contrast. Results supported a significant linear trend (\(t[108] = 3.556, p < .001\)) such that negative reactions increased linearly across Dayaknese, Javanese, and Madurese raters.

A line plot might be a useful choice in conveying the linear trend.

ggpubr::ggline(Ramdhani_df, x = "Rater", y = "Negative", xlab = "Ethnicity of Rater", linetype="solid",

ylab = "Negative Reaction", add = c("mean_sd", "jitter"), title = "Linear Trend for Rater Main Effect")

8.6 APA Style Results

First, I am loathe to term anything “final.” In academia, there is always the possibility or revision. Given that I demonstrated a number of options in the workflow (with more in the appendix), let me first show the workflow with the particular path I took:

That is, I first tested the statistical assumptions and computed the omnibus ANOVA. Because there was a significant interaction effect, I followed with examination of the simple main effect of photo stimulus within ethnicity of the rater. It made sense to me to conduct the all post hoc pairwise comparisons within this simple main effect. In light of that, here’s how I might write it up:

A 3 X 2 ANOVA was conducted to evaluate the effects of rater ethnicity (3 levels, Dayaknese, Madurese, Javanese) and photo stimulus (2 levels, Dayaknese on Madurese,) on negative reactions to the photo stimuli. Factorial ANOVA assumes that the dependent variable is normally is distributed for all cells in the design. Skew and kurtosis values for each factorial combinations fell below the guidelines recommended by Kline (2016a). That is, they were below the absolute values of 3 for skew and 10 for kurtosis. Similarly, no extreme outliers were identified and results of the Shapiro-Wilk normality test (applied to the residuals from the factorial ANOVA model) suggested that model residuals did not differ significantly from a normal distribution (\(W = 0.9846, p = 0.234\)). Results of Levene’s test for equality of error variances indicated a violation of the homogeneity of variance assumption, (\(F[5, 105] = 8.834, p < 0.001\)). Given that cell sample sizes were roughly equal and greater than 15, each; (Green & Salkind, 2017c) we proceded with the two-way ANOVA.

Computing sums of squares with a Type II approach, the results for the ANOVA indicated a significant main effect for ethnicity of the rater (\(F[2, 105] = 8.098, p < 0.001, \eta ^{2} = 0.134\)), a significant main effect for photo stimulus, (\(F[1, 105] = 19.346, p < 0.001, \eta ^{2} = 0.156\)), and a significant interaction effect (\(F[2, 105] = 5.696, p = .004, \eta ^{2} = 0.098\)).

To explore the interaction effect, we followed with a test of the simple main effect of photo stimulus within the ethnicity of the rater. That is, with separate one-way ANOVAs (chosen, in part, to mitigate violation of the homogeneity of variance assumption (Kassambara, n.d.-a)) we examined the effect of the photo stimulus within the Dayaknese, Madurese, and Javanese groups. To control for Type I error across the three simple main effects, we set alpha at .017 (.05/3). Results indicated significant differences for Dayaknese (\(F [1, 33] = 50.404, p < 0.001, \eta ^{2} = 0.604\)) and Javanese ethnic groups \((F [1, 35] = 17.183, p < 0.001, \eta ^{2} = 0.329)\), but not for the Madurese ethnic group \((F [1, 37] < 0.001, p = .993, \eta ^{2} < .001)\). As illustrated in Figure 1, the Dayaknese and Javanese raters both reported stronger negative reactions to the Madurese. The differences in ratings for the Madurese were not statistically significantly different. In this way, the rater’s ethnic group moderated the relationship between the photo stimulus and negative reactions.

We can simply call the Figure we created before:

apaTables::apa.2way.table(iv1 = Rater, iv2 = Photo, dv = Negative, data = Ramdhani_df, landscape=TRUE, table.number = 1, filename="Table_1_MeansSDs.doc")##

##

## Table 1

##

## Means and standard deviations for Negative as a function of a 3(Rater) X 2(Photo) design

##

## Photo

## Dayaknese Madurese

## Rater M SD M SD

## Dayaknese 1.82 0.77 3.13 0.16

## Javanese 2.52 0.74 3.46 0.64

## Madurese 3.30 1.03 3.30 1.33

##

## Note. M and SD represent mean and standard deviation, respectively.apaTables::apa.aov.table(TwoWay_neg, filename = "Table_2_effects.doc", table.number = 2, type = "II")##

##

## Table 2

##

## ANOVA results using Negative as the dependent variable

##

##

## Predictor SS df MS F p partial_eta2 CI_90_partial_eta2

## Rater 12.24 2 6.12 8.10 .001 .13