Chapter 2 Training Models in Professional Psychology

This lesson compares and contrasts training models in professional psychology. To that end, I review:

- The push and pull of science and practice

- Training models (and accreditation)

- Scientist-practitioner

- Scholar practitioner

- Clinical scientist

- Local clinical scientist

- Programmatic differences as a function of training model

- The future of models – and one in particular

- The Research & Dissertation Guidelines in the doctoral psychology programs at SPU.

2.2 The Push and Pull of Science and Practice

Meehl’s (1954, p. 4) catharsis regarding the dissociated state of science and practice is below. We’ll turn it into Reader’s Theater by following Stricker’s (1997) recommendation to substitute scientist for the statistical metnod and practitioner or the clinical method. If you were in my classroom I would ask or volunteers to be the NARRATOR, the advocate for the scientist (italics) and advocate forthe practitioner (bold).

The (statistical method) scientist is often called operational, communicable, verifiable, public, objective, reliable, behavioral, testable, rigorous, scientific, precise, careful, trustworthy, experimental, quantitative, down-to-earth, hardheaded, empirical, mathematical, and sound. Those who dislike the method scientist consider them to be mechanical, atomistic, additive, cut and dried, artificial, unreal, arbitrary, incomplete, dead, pedantic, fractionated, trivial, forced, static, superficial, rigid, sterile, academic, oversimplified, pseudoscientific, and blind. The (clinical method) practitioner, on the other hand, is labeled by their proponents as dynamic, global, meaningful, holistic, subtle, sympathetic, configural, patterned, organized, rich, deep, genuine, sensitive, sophisticated, real, living, concrete, natural, true to life, and understanding. The critics of the (clinical method) practitioner are likely to view them as mystical, transcendent, metaphysical, super-mundane, vague, hazy, subjective, unscientific, unreliable, crude, private, unverifiable, qualitative, primitive, prescientific, sloppy, uncontrolled, careless, verbalistic, intuitive, and muddleheaded.

2.3 Training Models & Accreditation

APA accredited programs must (but most all grad psych programs do):

- define and articulate their own training philosophies,

- demonstrate that the outcomes of the training are consistent with the model

- do so because of the need for (and value of) public accountability

All currently accredited doctoral programs in clinical have a “pure” model affiliation or some variation thereof.

Most common models:

- clinical scientist,

- scientist-practitioner,

- with updated proposal for scientist-practitioner-advocate (Mallinckrodt et al., 2014)

- practitioner-scholar models

2.3.1 Scientist~Practitioner (SP) Model

The scientist~practitioner model is also known as the Boulder Model. It originated in 1949 with formal articulation in 1950 (Raimy, 1950). It is characterized by the following:

- Primary goal: equal provision of extensive training in psychological research and the applications of that research to eventual practice—that is, to the creation of the SP psychologist (Cherry et al., 2000).

- Began in clinical psychology; prominent training model in school, counseling, and I/O psych programs

- Model re-articulated at the National Conference on SP Education and Training for the Professional Practice of Psychology, Gainesville, FL, 1990 (Belar & Perry, 1992).

- Major theme: SP ≠ summation; SP ≠ continuum; SP = integration. New symbols: not S-P, but SXP or S~P

- Major theme: “The graduate of this training model is capable of functioning as an investigator and as a practitioner, and may function as either or both, consistent with the highest standards in psychology.”

- Training components of the SP model (Belar & Perry, 1992):

- Didactic scientific

- Didactic practice core

- Experiential scientific

- Professional practice experiential

- Integration of Education & Training

- System components (faculty, setting, evaluation procedures)

- In spite of this idealism, many argue that the S~P model is really an S model (e.g., Stricker & Trierweiler, 2006). Just what evidence is there or this?

A mixed methods study (Ridley & Laird, 2015) surveyed training directors in counseling psychology programs. Training directors indicated the degree to which each of nine program components fell in the continuum of science-to-practice. Table 6 in the manuscript shows the results (and is worth a look). Overall the programs leaned heavily toward “science” with four of the criteria being rated as “heavily science.” These included

- Statistics and resaerch methodology

- Psychology core course

- Resaerch experiences

- Dissertation experiences

Only practica courses were rated as heavily practice. The remaining criteria fell between the two. These included:

- Criteria for student evaluations.

- Counseling psychology core courses

- Our program overall

- Diagnostic/assessment courses.

2.3.2 Scholar-Practitioner (SCH-P) Model

The scholar-practitioner model is also known as the Vail model. It originated in 1973 when the National Institute for Mental Health and the American Psychological Association met in Vail, Colorado. It is characterized by the following:

- Primary goal: the preparation for “delivery of human services in a manner that is effective and responsive to individual needs, societal needs, and diversity” (McHolland, 1992, p. 159).

- Operationalized as the capacity to conduct disciplined inquiry (rather than producing controlled lab or field research)

- Ivey and Leppaluoto (1975) summarized the major emphases of this model; the original summary is found in Korman (1974):

- Awareness of values; not promotion of “right values”

- Attention to human diversity and culture

- Scientist practitioner: professional training as a legitimate alternative.

- Individual v program training (e.g., continuing education [CE])

- Specifically, the conferands concluded that when primary training emphasis is on the production of new knowledge, the Ph.D. is appropriate; when primary emphasis is on professional services, evaluation, and improving services, the Psy.D. is appropriate.

2.3.3 Clinical Scientist Model

The clinical science model was created by the Academy of Psychological Clinical Science in 1974. It is characterized by the following:

- Primary goal: to provide training in the production of scientific research on clinical problems and its application to those problems (Academy of Psychological Clinical Science, 1997).

- “Clinical science” is defined as a psychological science directed at the promotion of adaptive functioning; at the assessment, understanding, amelioration, and prevention of human problems in behavior, affect, cognition or health; and at the application of knowledge in ways consistent with scientific evidence. The Academy’s emphasis on the term “science” underscores its commitment to empirical approaches to evaluating the validity and utility of testable hypotheses and to advancing knowledge by this method.

A flavor of this model can be found in a McFall’s (1991) Manifesto for a Science of Clinical Psychologyhttp://apsychoserver.psych.arizona.edu/JJBAReprints/PSYC621/McFall_Manifesto_1991.pdf). McFcall declared that “Scientific clinical psychology is the only legitimate and acceptable form of clinical psychology” should be a “Cardinal Principle.” To that end:

- First Corollary: Psychological services should not be administered to the public (except under strict experimental control) until they have satisfied these four - - The exact nature of the service must be described clearly.

- The claimed benefits of the service must be stated explicitly.

- These claimed benefits must be validated scientifically

- Possible negative side effects that might outweigh any benefits must be ruled out empirically.

- Second Corollary: The primary and overriding objective of doctoral training programs in clinical psychology must be to produce the most competent clinical scientists possible.

- Change is constant;PCSAS offers an accreditation program that competes with APA’s.

2.3.4 Local Clinical Scientist Model (LCS)

The local clinical scientist model emerged in a series of writing (Stricker, 1997; Stricker & Trierweiler, 2006, 1995; Trierweiler et al., 2010; Trierweiler & Stricker, 1998). It is characterized by the following:

- Elaborates, extends, optimizes, makes real the Boulder scientist-practitioner model

- A scientific approach and inquiring attitude of curiosity, skepticism, hypothesis testing and reframing within the local setting

- Breaking it down:

- clinical scientist reflects our commitment to psychology as both a scientific discipline and a healthcare profession.

- local refers to the particular application of general science, within local cultures, including the idiographic aspects of persons, families, and communities, in specific space-time and relational contexts

2.3.5 And What Does It Mean?

Norcross et al.(2020) evaluated 20-year trends of counseling psychology programs in terms of program, student, and faculty comparisons – and also compared it to clinical psychology. The tables in the Norcross et al. manuscript are worth reviewing. Generally results demonstrated:

- there are more applicants to research-oriented programs

- a fewer percentage of students are to research-oriented programs

- there is more funding in research oriented programs

- there are non-significant differences for gender

- there is a lower percent of students of color in practice-oriented programs

- there is a shorter time required to complete practice oriented programs

- GREs are higher in research oriented programs

Regarding differences between counseling psychology and clinical psychology programs, Norcross et al.(2020) reported that there were non-significant differences in the number of incoming students each year, but that there was greater numbers of applications received and, thereore, a smaller proportion of students accepted in clinical psychology programs. There was not a statistically significant diference in the percentage of students receiving full tuition waivers and assistantships. Regarding student characteristics, clinical psychology programs had somewhat higher GRE scores and students were more likely to enter having completed a bachelor’s degree. Regarding counseling psychology programs, more students had completed a master’s level degree. There were more female students in clinical psychology programs; there were more ethnic minority students and international students in counseling psychology programs.

Regarding theoretical orientation, counseling psychology programs were more likely to be psychodynamic/psychoanalytic, family systems/systems, and existential/humanistic. Clinical psychology programs were more likely to be applied behavioral analysis/radical behavioral and cognitive/cognitive-behavioral.Clinical psychology programs reported a stronger research-practice emphasis.

Cherry et al. (2000) examined outcomes related to training model. Perhaps not surprisingly, research and publication productivity was highest among programs with a clinical scientist training model, followed by the scientist-practitioner training model, followed by the scholar-practitioner model. Service delivery was the the opposite order. Regarding post-doctoral employment settings, graduates from clinical psychology programs often held employment in academic settings. Graduates of scholar-practitioner programs most often held employment in community mental health centers and other/multiple settings. Graduates from scientist-practitioner programs had more of a diverse profile in post-doctoral employment.

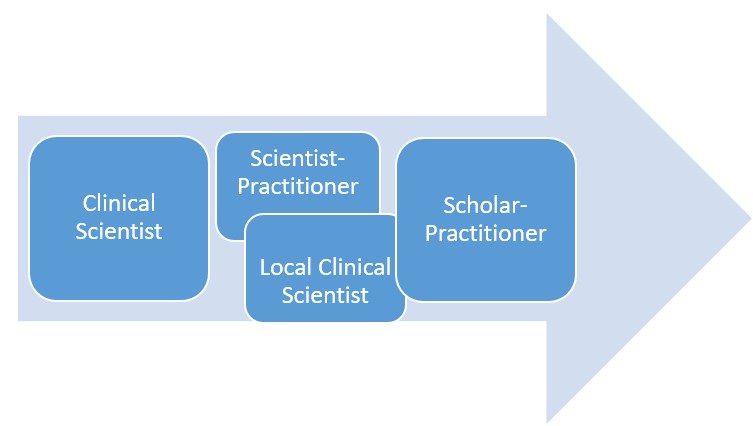

A figure reflecting the research/science and practice/service continuum

2.3.6 What Lies Ahead?

Mallinckrodt et al. (2014) has proposed a scientist-practitioner-advocate training model for doctoral training in professional psychology, “designed to more effectively meet the needs of clients whose presenting problems are rooted in a sociocultural context of oppression and unjust distribution of resources and opportunities.” This model has been represented with three intersecting circles:

- where science and practice overlap, science informs practice and practice generates research ideas,

- where practice and advocacy overlap, there is advocacy for clients, empowering them to advocate for themselves,

- where advocacy and science overlap, there is action resaerch and research as advocacy,

- at the center where all three overlap is a practicum in social justice advocacy.

The scientist-practitioner-advocate model prioritizes four outcomes:

- Developing an understanding how the context of social problems impacts the lives of individuals;

- Demonstrating skills in the methods of social action research and be able to use empirical skills as tools for advocacy and to promote social change;

- Developing effective interventions targeted at the level of institutions or systems influencing public policy decisions and evaluating the effectiveness of these interventions; and

- Learning to work with individual clients to help them make informed choices about the cost and benefits of engaging in advocacy for themselves.

The University of Tennessee Counseling Psychology Program and provides a practical example of how it has been operationalized in their program.

Accredited programs are required to provide details about their training models in their program materials. These are often foundin doctoral handbooks, research and dissertation guidelines, and clinical trainng guidelines.

2.4 Suggestions for Practice

If you are in a graduate training program in psychology (or considering the possibility of further trainng and education):

- Does your program have a specified and articulated model?

- If yes, what is it? How does it compare to the descriptions in this lesson?

- If no, based on what you know about the program how would you describe it?

- Interview at least two faculty. How do they identify and describe the trainng model of the program?

References

Cherry, D. K., Messenger, L. C., & Jacoby, A. M. (2000). An examination of training model outcomes in clinical psychology programs. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 31(5), 562–568. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.31.5.562

Ivey, A. E., & Leppaluoto, J. R. (1975). Changes ahead Implications of the Vail Conference. Personnel & Guidance Journal, 53(10), 747–752. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2164-4918.1975.tb04075.x

Korman, M. (1974). National conference on levels and patterns of professional training in psychology: The major themes. American Psychologist, 29(6), 441–449. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0036469

Mallinckrodt, B., Miles, J. R., & Levy, J. J. (2014). The scientist-practitioner-advocate model: Addressing contemporary training needs for social justice advocacy. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 8(4), 303–311. https://doi.org/10.1037/tep0000045

McFall, R. M. (1991). Manifesto for a Science of Clinical Psychology. Clinical Psychologist, 44(6), 75–88.

McHolland, J. D. (1992). National Council of Schools of Professional Psychology core curriculum conference resolutions. In R. L. Peterson, J. D. McHolland, R. J. Bent, E. Davis-Russell, G. E. Edwall, K. Polite, D. L. Singer, & G. Stricker (Eds.), The core curriculum in professional psychology. (pp. 155–166). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10103-029

Meehl, P. E. (1954). Clinical versus statistical prediction: A theoretical analysis and a review of the evidence. University of Minnesota Press. https://doi.org/10.1037/11281-000

Norcross, J. C., Sayette, M. A., & Martin-Wagar, C. A. (2020). Doctoral training in counseling psychology: Analyses of 20-year trends, differences across the practice-research continuum, and comparisons with clinical psychology. Training and Education in Professional Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/tep0000306

Raimy, V. C. (1950). Training in clinical psychology, (Conference on Graduate Education in Clinical Psychology, Ed.). Prentice-Hall.

Ridley, C., & Laird, V. (2015). The scientist–practitioner model in counseling psychology programs: A survey of training directors. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 28(3), 235–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2015.1047440

Stricker, G. (1997). Are science and practice commensurable? American Psychologist, 52(4), 442–448. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.52.4.442

Stricker, G., & Trierweiler, S. J. (2006). The local clinical scientist: A bridge between science and practice. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, S(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1037/1931-3918.S.1.37

Stricker, G., & Trierweiler, S. J. (1995). The local clinical scientist: A bridge between science and practice. American Psychologist, 50(12), 995–1002. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.50.12.995

Trierweiler, S. J., & Stricker, G. (1998). The scientific practice of professional psychology. Plenum Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-1944-1

Trierweiler, S. J., Stricker, G., & Peterson, R. L. (2010). The research and evaluation competency: The local clinical scientist—Review, current status, future directions. In M. B. Kenkel & R. L. Peterson (Eds.), Competency-based education for professional psychology. (pp. 125–141). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12068-007